|

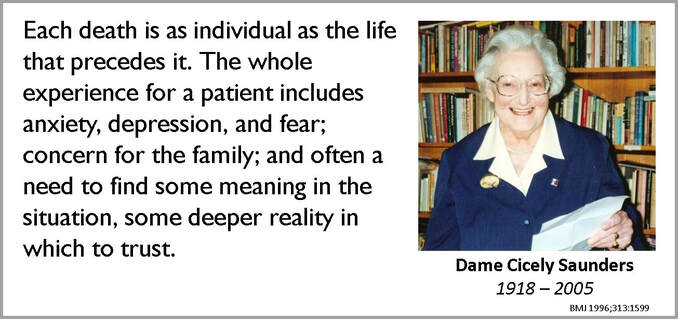

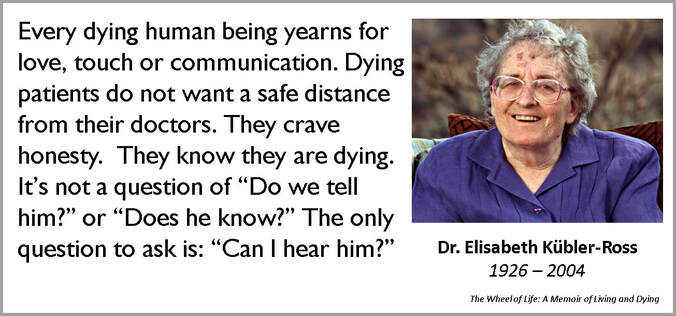

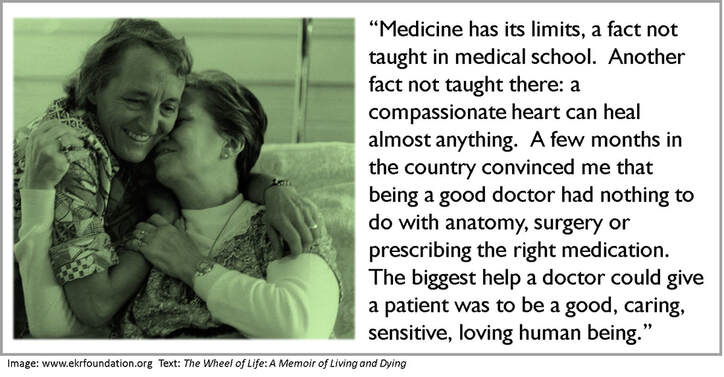

These days we have several days dedicated to one thing or the other. Tomorrow, October 12, 2019, is earmarked for something that concerns life and death, the comfortable, dignified transition from one to the other and life thereafter. The second Saturday of every October is World Hospice and Palliative Care Day. Unless you catch a stray headline or a post brushes by while you wade through social media, you may miss the significance of October 12, 2019. Unless you suffer from a chronic illness or you care for someone who does, or you help both as a palliative care professional. In which case, it is a day that would probably mean the world to you. This is the right occasion to remember two women who were strong enough to be compassionate. They were both discouraged from the medical profession when they started their education. Then the world plunged into war and they boldly went into the uncommon profession of compassionate care. They deliberately chose to sit next to and hold the hand of pain and misery. So that they could teach an uncaring world to understand and manage both, and death, better. Meet Dame Cicely Saunders and Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, the Pioneers of Compassionate Care. Dame Cicely Saunders |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed