|

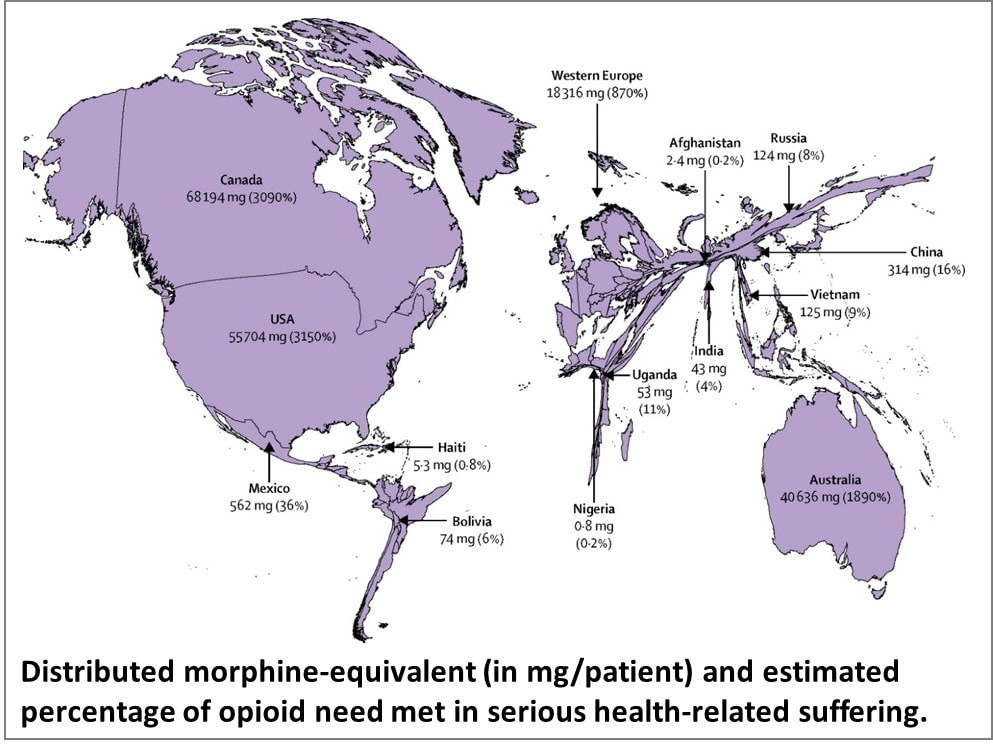

This is inspired by a talk delivered by Dr M R Rajagopal, Emeritus Chairman, Pallium India, as part of the seminar series “Palliative Care and the Motives of Medicine”, organized by the Harvard Medical School Department of Global Health and Social Medicine. This is written in his voice with his permission. The doctors attended to her leg and restored her sight. But were they solely responsible for giving her “life” back to her? What about the sweeper who provided food every day so that she did not have to consider suicide, as her son had suggested? What about the social media support that gave a roof over their heads? What is the motive of medicine? Are we here just to diagnose and treat diseases? Or is it a bit more than that? We may have come into it for different reasons but once we are in the field of medicine, we realize what a huge privilege it is to be part of healthcare. We find ourselves in a position to make the most difference to other people’s lives. We see people at the most vulnerable times in their lives and at times become the instruments to help them rise from the depths and smile again. To actually provide healthcare for all, we may sometimes have to travel over difficult terrain. At times, we have to strike a new path because at the other end there is somebody who belongs to 84% of the global population, without access to quality healthcare. They cannot get to us, we have to reach healthcare to them where they are, when they need it. Does that sound frightening? It takes more than a doctor Ironic as it might sound, I got to meet that helpless mother and son when I was leaving a World Palliative Care Day function. The 12-year-old boy had been sent with the hope that someone would be there at the function to help his mother. Her one leg was fully wrapped in an ugly bandage. And she was blind. She was about 40, a single mother abandoned by her husband. She had been a diabetic since the age of three. Diabetes had stolen her sight four years ago. A surgeon had said she would need an above-knee amputation. Of course, she was in significant pain, “like someone is cutting my leg with an axe.” She lived in a shack that belonged to someone else. She told me about a weekend when they had to starve. Hungry and frustrated, the son said, “Mom, let us kill ourselves. I cannot bear this hunger anymore.” Mom replied, “Son, today is Sunday. Let’s wait. I will find some way.” Somehow, they got across to a healthcare center. Luckily, they found a very humane doctor there who put them up for three months before I got to see them. They survived on the meal provided by a sweeper at the center every morning. They landed at the palliative care day function where I met them first because a kind nurse at the health center had directed them there. A definition distant from reality There are several definitions of palliative care today. Most of us working in the domain abide by what the World Health Organization had stated 21 years ago. Among other things, it prescribes palliative care for those with “life-threatening illness.” Let us go back to the mother we just met. She is diabetic; does she qualify? She is blind; does she qualify? More than anything else, does hunger qualify? The same persistent hunger that almost drove them to suicide? We cannot be rendered helpless by a definition. After all, such definitions tend to come from the 15% of the world that is rich and where all the meticulous studies happen. It gets applied to the 85% of people living in low-and-middle income countries in drastically different conditions. Do such definitions bind or liberate? Let us go back to the fundamental issue. What really is healthcare? When we keep someone’s heart beating, are we providing healthcare? What is the duty of the healthcare provider? The law does not define it in India. But the Indian Council of Medical Research, a statutory body, defines that duty as: “To mitigate suffering. To cure sometimes, to relieve often, and to comfort always.” And the ICMR emphasizes there is no exception to this rule. How many of us are aware of that definition? Do we practice it? Or do we stick to what we learn from the textbooks as dictated by medical institutions in 15% of the world, the high-income world? Palliation as mitigation If you are a healthcare professional and you have not been taught how to mitigate suffering or do not accept it as your primary responsibility, we in palliative care will be happy to help you. Not that we have all the answers. At least, we try. Because mitigating suffering is our primary motive. Opioids are one of the primary tools we use for relief from moderate to severe pain. In 2017, a Lancet Commission Report depicted access to opioids (which translates to access to pain relief) across the world. You can easily make out which country is obese, and which is malnourished when it comes to opioid access. The trick is to strike the right balance between easy availability and the necessary restrictions to prevent abuse and misuse. While we applaud western European countries for getting that balance right, let us not forget Kerala. In this tiny state right at the bottom of India, access to opioids is 16-times more than the national average. In the low-income Uganda, opioid access is three times better than what India claims. So, this shows it can be done. But why is it not happening universally? Is it because relieving pain or mitigating suffering is not a commercially attractive proposition for the industry that is at the heart of healthcare? Adding cost to suffering A study published by The Lancet on December 13, 2017, pointed at a vulgar disparity of life (to borrow Arundhati Roy’s expression). Not only are we not doing what we ought to be doing, but we are letting catastrophic healthcare expenditure add to the pain. The study aimed to estimate the global incidence of what they called catastrophic health spending. They measured this by the percentage of people whose out-of-pocket health expenditures were large relative to their household income or consumption. You are welcome to read the study for yourself. Personally, I was saddened and shocked to note that India was among the 12 countries burdened the most by the cost of health: more than 55 million Indians driven below the poverty line by what they had to spend on health; 38 million of them by cost of medicines alone. Such catastrophic health spending is not only for living with an illness; it is also for end of life—with the dying process excruciatingly stretched out over weeks or months in a desperate effort to prolong life at all costs. Are we afraid of death? Do we tend measure the “success” of medicine by how long it can keep death away? Is it difficult for us to accept that if life were a sentence, death is simply the full stop at the end of it? In January 2022, drawing on multidisciplinary perspectives from around the globe on the value of death, the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death argued that “death and life are bound together: without death there would be no life.” The Commission proposed a new vision for death and dying. It called for “greater community involvement alongside health and social care services, and increased bereavement support.” Cruelty of forcing to stay alive Moving away from professional studies and reports, let me narrate a personal experience. One of the professors who taught me medicine developed dementia. She was not swallowing well, so she was put on intravenous feed, against the advice of many of us. She would keep pulling the tube out. So, they tied her up. As every doctor knows, physical restraints can cause a 44-fold increase in the patient’s agitation. She did become more violent, and they promptly tied her up tighter. Eventually she was intubated and ventilated. The family had to walk in every morning and every evening for five minutes each, watching their beloved person being killed in order to be kept alive. Her daughter lamented, “Here was a person who gave a lot of love to a lot of people. Did she deserve to die this way?” Even as I write this, the daughter is receiving psychiatric treatment. I do not think she was affected so much by the loss of her mother as by the cruel way medicine kept her alive until the last excruciating moment. Why do our efficient, kind-hearted doctors refuse to accept that death is a part of life? Why do they hold on to the mistaken belief that it is their duty to prolong life at all costs? Is life merely a beating heart? The National Cancer Grid, a brilliant conglomerate of about 300 cancer institutions in the country launched the initiative Choosing Wisely India around 2020. The objective was to “identify low-value and/or potentially harmful practices in cancer care in India.” It intended to “facilitate a conversation between patients, clinicians, hospitals and policy makers on delivering high quality, affordable cancer care.” The aim was also “to reduce unnecessary interventions to improve overall quality of care, reduce patient toxicity and reduce the financial burden on both the patient and the system.” One of the recommendations was, “Do not treat patients with advanced metastatic cancer in ICU unless there is an acutely reversible event.” Laudable, isn’t it? But we all know what happens in hospitals. A friend, a senior neurologist, once remarked that our corporate hospitals are like fortresses that the poor cannot get into, and the rich cannot get out of. I do not think he was joking. A 2019 JAMA paper stated that in European intensive care units, 90% of all patients were taken off life support and offered palliative care once it was clear further treatment was futile. And, in comparison, what is the situation in India? Only 30% are taken off futile life support, that too any without palliative care support. As much as 70% of them die in ICUs. The end is stretched, hour by cruel hour for the patient, day by interminable day for the family. Helping us is up to all of us Let me get back to that woman and her son one more time. Yes, we treated her symptoms and pain. That was relatively easy but definitely not enough. One of us posted her story on social media and requested help. Help came. We now had money to pay for a caregiver while the patient underwent retinal surgery. After years, she got to see her son again. A diabetologist and podiatrist helped her get back on her feet, with support. She held her son’s hand and walked to a new home, where they are now supported by a monthly allowance, thanks to donations from the community. There is a huge gap between what healthcare is and what it ought to be. No doctor and no palliative care specialist can fill it by themselves. Does that mean we hide behind a definition and shut our eyes to the problem? The German physician Rudolf Virchow had said: “Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing but medicine on a large scale. The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them.” Our palliative care team is taking small steps. We are far from perfect, and it is a huge mountain to climb. But we are trying. By doing our best to support patients. By talking to the community about what we are doing and how they can help. There are many who want to help. But do not know how. Money is not the only way. I believe it is beginning to work. It has to. Right now, it is up to us to solve this social, or rather, humanitarian problem. Every World Palliative Care Day is a special occasion when those who can help get together with those who need help to celebrate life. One such day, in the city of Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala, some 40 people came to the beach to wet their feet. So, what was special about that? These were all people confined to wheelchairs who could barely move out of their homes. It took four people to move each of them from home to the beach and back. So, it took about 160 people to make this happen. All doctors and nurses? No! They were students from two engineering colleges.

And what was their reward? One of the patients was a paraplegic who did not have normal sensation in her feet. She said, “the waves touching my feet is the best experience I have had in my whole life.” She couldn’t stop smiling. That was their reward. And that is the reward for all of us when the community joins hands with palliative care and medicine to mitigate suffering in the true, complete sense. We have a long way to go. We have just wet our feet.

0 Comments

Your client meeting is at 10 a.m. in a city two hours away. There is a flight at 4 a.m. and the next is at 9 a.m. You can take the first and maybe finish some work on the way. Or you can request the client to reschedule. What would you choose? If you are the kind who would compulsively pick the 4 a.m. flight, skip sleep altogether (“might as well finish some pending reports and nap on the flight”), you are keenly aware of the rising number of people being laid off and the churn in the upper ranks of the corporate world. Or, more likely, you are yet another victim of workism. Not too long ago, journalist Derek Thompson described workism as “the belief that work is not only necessary to economic production, but also the centerpiece of one’s identity and life’s purpose; and the belief that any policy to promote human welfare must always encourage more work.” More recently, in his TED talk, Azim Shariff, a psychology professor at the University of British Columbia, noted that we tend to see a harder-working person as a “more moral”, better work partner, even though they add no extra value. He describes workism as a culture that forces all of us to participate and punishes us if we do not keep up. So, “we end up putting more and more in regardless of what comes out the other side.” The more laborious the job, the greater the appreciation even though there may be no direct correlation to tangible results. Everything else becomes less important. Workism at work A senior management consultant (“no names, please”), currently helping an MNC bring about a culture change observes that workism is a convenient term to describe what is happening at work. “Workism is a series of corporate behaviors that have seeped into organizations over a period of time. It requires a conscious change in senior leaders to break the mold—like focusing on smarter delivery than longer hours, like linking performance to results than efforts.” It even extends to everyday attire. “We have this senior leader from the old generation who refuses to be seen in anything other than his suit and tie whether he is addressing two people over coffee or a dozen in the board room. Then we have a whole bunch of smart youngsters always clad in denims and tees, who would rather walk in, deliver, and get out than hang around and be seen to be busy.” So, is it just a matter of bridging the generation gap? “There is a lot more,” my consultant friend tells me. “The biggest challenge before us is to define the goal. The goal is not about the hours we put in and what we wear at work. Surprising as it might sound, we found the youngsters to be clearer about the goal than the seniors; they have a surprising level of clarity on what they would like to do and not to, in their work environment and are willing to defy the stereotypes.” Inverting the pyramid The team is now attempting a radical management exercise where the newbies on the block would talk about the organization’s goals in informal meetings with the seniors. This inversion of the pyramid is sure to spark conflicts initially. “But It’s worth the try. What better way to motivate individuals than by declaring that we will measure you for what you deliver, not for all those hours you clock in. We expect this to usher in a positive entrepreneurial mindset and a sense of real purpose.”

Charlotte Kramer, author of The Purpose Myth: Change the World, Not Your Job notes that “70% of millennials want to quit their jobs on the grounds of lack of purpose, and this should be no surprise; the positions we take were created to fill our pockets (if we’re lucky), not to fulfil our dreams. To think otherwise is to suggest that one’s individual purpose can be matched with a corporation’s purpose.” The challenge for organizations today is to inject every member of the team with a common purpose regardless of one’s role. That’s where culture-change exercises are likely to become more common across domains—to change good old feel-right workism to measurable, no-nonsense purpose-ism. The organization should be sensitive to the individual’s purpose; the individuals should willingly buy into the larger team goal. You took the later flight but after persuading the client to meet you for lunch at place you knew was her favorite. Not once did you open the laptop, but by the time the desserts arrived, you had convinced her of the positives of working with you. In turn, she convinced you to stay back and address her top team where you did use the slides to make a convincing case. That quadrupled your workload, but you chose to sleep during the late-night flight back home. You knew tomorrow would be excitingly busy. Moral: There are times when the “lazier” 9 a.m. flights are more productive than the "harder working” 4 a.m. flights. |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed