|

It has been nearly two months after I last visited my shop located about 20 km from my house. It is a trip I have done millions of times over nearly a decade; a route so familiar that I can do it blindfolded. Today my eyes are wide open as I cautiously drive down deserted roads. A policeman stops me at a junction, about 7 km from my shop. His expression changes as he looks at me closely. I explain where I am headed and what I do for a living. “I know,” he replies. I wonder if he is being sarcastic. “I have been to your shop,” he clarifies. He is not happy that my wife is accompanying me at a time when even one person has no business to be out and about. But then I am out on business, running a shop selling essentials and he knows that for a fact. He points me down the only route that is open. Finally, I reach the shop. It is mid-morning and the neighborhood is unusually quiet. I start pulling up the shutter and then stop, worried that it was very loud. My wife and I do some cleaning, rearrange the shelves, and sit in the shop for a while. There are no customers because I had not told anyone I was planning to open the shop. And I didn’t want to do that until I had official clearance from the police. For that I was determined to go the police station nearest the shop. We close the shop and head there. Policing for protection The inspector who heads the station emerges from inside just as we enter the station. I introduce myself. “I know you,” he stops me halfway. I can sense my wife looking at me. How come this fellow is known to so many policemen, she is probably wondering. “I started my duty before 7 a.m. keeping people away from the road,” the inspector continues. The last meal he had was the previous evening. So, he had just finished a late brunch before duty took him away again. I apologize for not recognizing him. I did have a regular customer from that police station, but that was— “I had come with my senior and you had given us both some coffee.” He mentions the name of the senior and it clicks. Before I repeat my apology, he asks another question. “Your shop is the one that always has those long south Indian bananas hanging outside, right?” I agree. No point in reminding him about my shop’s name. “If you are supposed to be selling essentials, you should have been there all these days, at least for limited hours. Why do you want to open now?” I explain that I was scared. And I wanted to make sure I obeyed the restrictions. Which is a polite way of saying that I was afraid of being beaten up by the police. From his smile, it is clear he understands. “Do you know that we are in a red zone? That means we are all in big danger from the virus. You think that the virus will simply go away? The virus will remain with us, even in our lungs at least for a couple of years. So, we have to take care. That is why we have to be bad and rude with everyone. Because people don’t understand that we are all in danger. All—you, me, them. We have to do our duty. We can’t work from home,” he pauses. I wonder if he has read up on the virus. “Listen, I am not complaining. We have nothing against the people we keep driving away. Our biggest problem is all the news and videos people share on the mobile. Everyone believes anything. And they love to show us worse than we are. After all, it is fun to share a video of a policeman supposedly beating up a poor vegetable fellow. We may not get to eat. We may share our food with 10 others who have nothing to eat, but that is not fun. Right?” He shrugs as if trying to shake off the mood he is in. Is corona goading us?He tells me I can open the shop for a limited duration as applicable to the zone. Then he describes how I can avoid overcrowding and the precautions I must take. All his directions make perfect sense. Before I leave, he warns, “If we find your shop is responsible for causing overcrowding, we will close the shop and take action against you.” There is no malice, it is just a statement of intention. On the way back home, I pass several policemen on duty. They are out in the sun, not safe at home. The only protection they had was a mask and a lathi—one against the virus, one for the people. In this fight against an evil entity we can’t see, are we and the police making each other the visible evil? Would we be happier with the virus if the police didn’t use their lathis? Is Covid setting us up, goading us all to be lesser beings? I reach home and send a WhatsApp message to all my customers that I was opening again and what they needed to do to help me stay open. As I head to the shop the next morning, I wonder if this is the return of the normal. After all, normal never stays new for long. We make sure it doesn’t. This post is triggered by the tone and substance of the WhatsApp message my anonymous shopkeeper friend broadcast. Far from being a dry announcement, it was eager to serve again, apologetic for staying away for long, joyous to be with friends again and anxious to ensure everyone bought well and stayed safe. Yes, it was infectious.

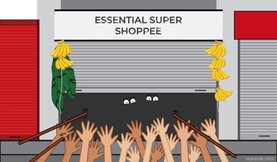

About the graphic. It must not have been easy for a busy designer who takes appetizing images of food to digress into illustration, but sportingly she went bananas for this piece. Thanks, Tasneem Syed!

1 Comment

Many happy returns, we say. At least once a year. What should we say when that wish is no longer a blessing but a curse?

You never see him at rest. If you hear the gate opening when the birds announce the rising sun, it is him with a vessel full of frothing milk, that he has just drawn from the cow. Are you willing to forgo your afternoon nap and walk a few meters to the coconut plantation that kisses the edge of the backwaters? You will see him there at work. He will not stop working but if you can walk along and pay attention, he will readily share his wisdom in gentle words. If you are not distracted by the water birds following the tractor, he will explain the mechanics and commercials of cultivating paddy. He may even offer you a tender coconut to savor. During the day, you will find him zipping about on his motorcycle. Errands never end. There are at least five homes of the extended family that count on his visits so that things get done. Then there are visits to the bank, to the panchayat office. He barely has time. If he spots you walking by, he will stop, park the bike and talk as if he has all the time for you. You will not want to get too close to the cows when he is tending to them in the shed next to the house. They do not look very friendly and are given to shaking their heads, making their horns bang noisily against the wooden railings. He remonstrates with one for not eating properly. There comes a prancing calf that gets a hug and a kiss. He has simply become one of them. You watch and wonder. The pages of the calendar keep flipping, bringing along the special day. He makes a special visit to the temple and there is a special sweet dish cooking at home. Looking at his hearty smile you sincerely wish the day would return many happy times. He is special. He deserves it. When that day came the last time, you did not want to wish him that. He was laid low by cancer. You flinched at the sight of the helpless figure on the bed, all bones and bedsores. You saw an apology on his face for not being able to get up and talk to you and share tea with you. He is gone. At last. All of us must. But not the lingering way he did. What do you say when, to wish for even one more return of the day, would be so insensitive, so cruel? Keeping in mind the only gift that matters and the inevitability of the end, perhaps it is time we learned to say, “Live full, die well.” |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed