|

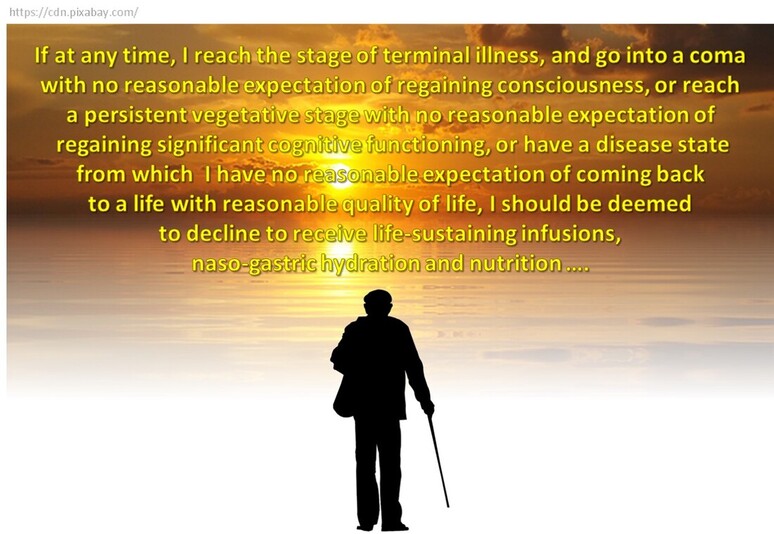

You know it is time. The disease has already won. You are ready to let go. But your family is not, nor are the doctors. As you lie there helpless, connected to so many tubes and machines, you sense your loved ones beyond the door, their fear, their sorrow. You wonder how they must be sacrificing to pay for all this. You want them to sit near you and hold your hand. And talk to you even if you can't respond. You want to tell them you love them and will always do. You know they love you, too. That is why you want them to remove all the tubes and machines. And just be with you at home, while you take leave. In peace, with dignity. If only you had told them how you wanted to go, when you could. The Guardian recently reported a study that found “the brain shields us from existential fear by categorising death as an unfortunate event that only befalls other people”. In other words, we are wired to deny life's only certainty, death. That being the case, it can be difficult to document our preferences about death. How can we think and discuss about how we want to be treated (or not) should we reach a terminal stage, a point of no return? But, think we ought to. Discuss we should. Document we must. The Supreme Court of India gave legal sanction to this “advance medical directive” or “living will” on March 9, 2018. The Supreme Court ruled that “in specific circumstances, a person has the right to decide against artificial life support by creating a living will,” and that “the right to life and liberty, enshrined under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, also includes the right to die peacefully and with dignity.” Delivering the judgment, Chief Justice Dipak Mishra observed: “Should we not allow them to cross the door and meet death with dignity? For some, even their death could be a moment of celebration.” Will, living and deadDespite the ruling by the apex court, a living will remains a touchy issue. In 2015, three national medical associations of neurologists, intensivists and palliative care physicians came together to form the End of Life Care in India Task force (ELICIT). Dr Roop Gursahani, a consulting neurologist, who is part of ELICIT, says we “need to make conversations about death natural and not forced”. He points out that a living will “takes care of one’s healthcare decisions at the end of life." While living will formats can be easily downloaded from several sources (here is one), the government is yet to translate the Supreme Court ruling into enforceable procedures. Some experts feel what the court has suggested is too restrictive. You need to be certified terminally ill first, which may be too late. Also, the will needs to be countersigned by a judicial magistrate first class, who is not within easy reach of most people. Nevertheless, it is prudent to make a living will and communicate your preferences to your loved ones and those responsible for your health care. As it is difficult to plan for every eventuality, you can leave it to the discretion of one or two people whom you trust to implement your will. Financial planning Mention “will”, and one tends to think of a very legal-looking document. And of lawyers, and members of the family throwing not-necessarily friendly looks at one another. You also think of someone very ill, unlikely to be helped by all that he (or she) owns and has willed it away for others to enjoy. What matters most at the end is peace and dignity, at least for the patient. However, there is no wishing away the money elephant in the room. Fortunately, compared to the ethical and medical issues, planning for financial security is easier, provided you are willing to start long before it is time to make that final transition. Matters of money and anticipation when life is in transition A Certified Financial Planner, Sneha Jaggar recently qualified as a Financial Transitionist. Here she answers questions about finance and other issues at the time of life’s final transition. Q: Whether you wish to try everything possible to prolong life or decline heroic medical interventions, there are financial implications either way. How does one tackle this? Sneha: Life is a very delicate topic. My life is more precious to my near and dear ones than I perceive it to be. And this is often observed when a family member has to decide about treatment at the end of a loved one's life. These decisions are emotionally and financially draining if we do not know what the patient wants. You can help your family by having three things in place:

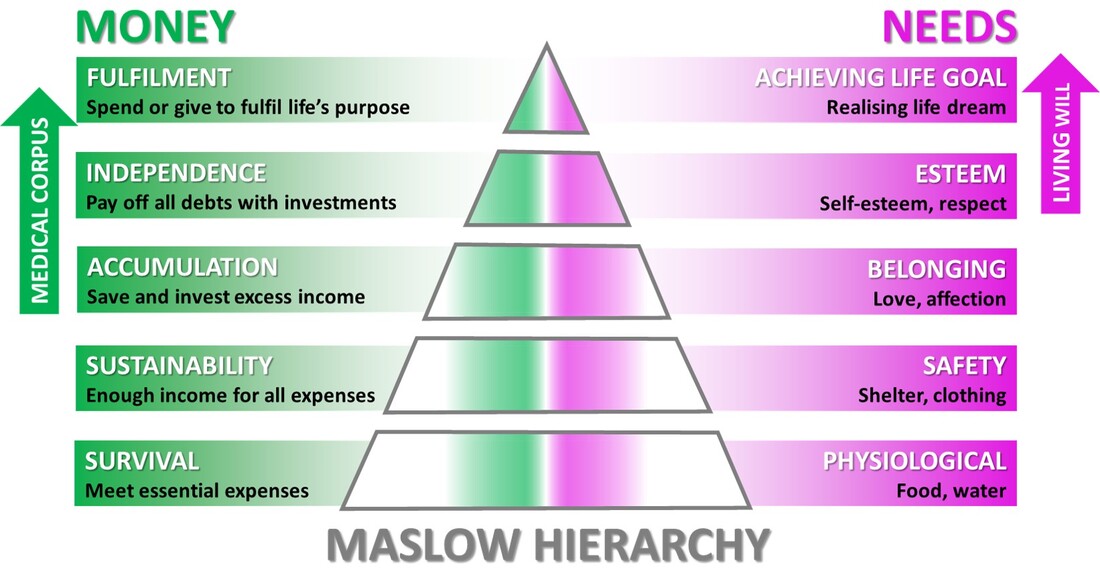

You help clients plan their life goals after retirement. Do you talk of terminal illness? Is it possible to quantify this requirement? Like I said, from the financial planning point of view, everyone should have the four basic insurance policies in place. However, as it keeps on increasing with one’s age, paying health insurance premium would be difficult after retirement. Additionally, medical inflation (cost of medical care) is presently the highest at 12% per annum. This is the reason why we need a separate medical corpus for the post-retirement period. When I speak to clients on retirement, I start by understanding their expectations. Many are practical. Some I need to sensitize about age-related illnesses. How much would they value their financial freedom should such a situation arise? The value of the corpus would depend on the individual and family, their standard of living, cash flow, net worth in the pre-retirement period, etc. These days parents prefer not to burden their children with end-of-life care. Do you have that conversation with the parent(s) or the children or both? Today, most parents are self-sufficient. However, they do need help in case of a medical emergency. Those who are still earning and want to be self-sufficient can build up a buffer for these emergencies. When I begin my conversations with parents, I try to understand where they stand in the Maslow hierarchy. When I know it is the right time to speak about legacy and wealth migration, I chart out detailed sessions with the parents first and then their children. During these sessions I speak not only about estate planning, but also about palliative care, end-of-life treatment and living will. Once the parents understand all this and are confident enough to talk about it, I involve the children. However, in spite of the Supreme Court ruling, the legal status and practical applicability of the living will remain hazy. Therefore, I tell my clients they should consult their doctors and lawyers about this. One son abroad is fully bearing the cost of treatment. The second son in India is the 24-hour caregiver but has no money. They have conflicting views on what is best for the patient, their father. How do you tackle such a situation? In this scenario of transition, both the sons are in what we call the anticipation stage. You expect an event (end of father’s life) to occur but that has not yet happened. Both the sons portray struggle traits in their behaviour. The one abroad is probably feeling helpless as he cannot be present physically. The other one is experiencing emotional fatigue, where he cannot see his father suffering in front of his own eyes. As a financial transitionist, I would use certain tools to help them clear their fears and frustrations. Then help them arrive at a decision that both are happy with and is best for the father, too. If one has drawn up clear plans after discussions, how to ensure those are enforced when the patient is totally helpless? For example, the patient may expect a certain course of action but the spouse may act entirely differently. I cannot speak on the legal position, but some of the issues here are that of understanding and expectation. Generally, financial planners/advisors talk about goals because they’re trained to craft them, and create timelines and benchmarks. Expectations are the spaces that exist in the narrative about goals. Some are vague, some are small, and some are fleeting. Regardless, they’re all important because they influence the thoughts and behaviour of the client. What makes expectations complicated is that they’re frequently not verbalized. Someone may or may not be correct about their perception of the expectations of others, even their near and dear ones. Regardless, expectations can create an unseen but powerful undercurrent that influences relationships, behaviour and satisfaction. When left unexplained while making important decisions, those details become little spaces of uncertainty that could create financial and personal problems. I help clients write down their assumptions and expectations regarding an event yet to occur. I also discuss the time horizons to gain greater clarity about why they have these expectations. Based on similarities and differences, I help determine the next steps most relevant to them. It could involve separate one-on-one discussions or joint sessions. This helps verbalize the thoughts and expectations one has of the other and brings the differences to light. Then it becomes easier to work towards a common ground. When is the right time to talk of the living will? Again, when I introduce this topic would depend on my comfort level with the client, his or her age, life circumstances, background and standard of living. For example, if I’m talking to a just-married couple, I will have to be rather sensitive about broaching the subject of a medical corpus. However, if either or both of them have already had close encounters of the medical kind involving someone close, they would be already sensitized. It would be easier to talk about medical corpus, end-of-life treatment and living will. In your opinion, what can be done to minimize confusion and ensure dignity at the end of life? Just to sum up, five actions can help a lot:

Have another question? Ask Sneha Jaggar.

3 Comments

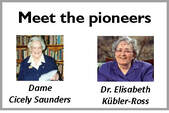

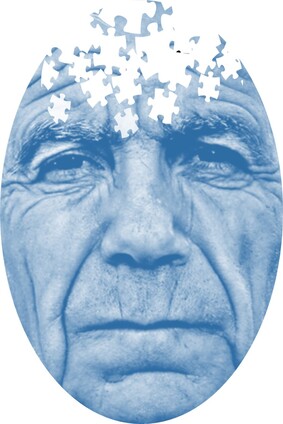

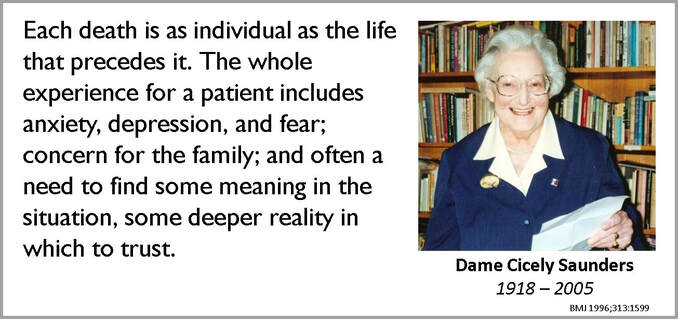

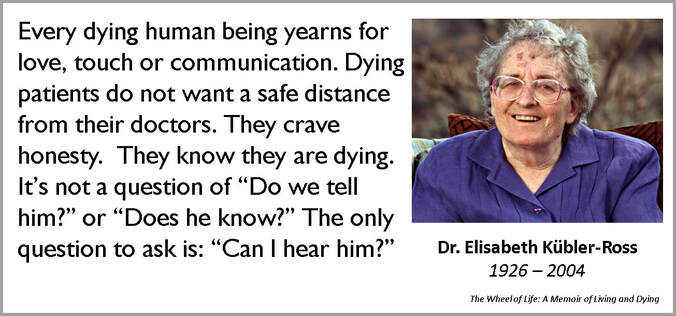

It was February. I stood barefoot on the beach, watching the waves rise and fall mightily, roll over my feet gently and then immediately return to meet the vast ocean. The evening sun spread its colours across the sky. Tiny boats dotted the horizon, returning to the shore. The smell of the sea filled my nostrils. I wondered how this came to be my life. How did I end up giving birth, then losing my 4-year-old daughter to cancer (brain tumour) after 18 months of struggle (of which 14 months were in palliative care)? How did my family and I survive the trauma? How did I come to stand on this beach without Ira? Clinging to elusive hopeI had noticed minor tremors in Ira’s left hand in March 2017. Initially it was attributed to motor development issues. After a few visits to the paediatrician and the neurologist, and a scan later, the diagnosis was confirmed—thalamic glioma. A surgery was imperative as the tumour pressed on several parts of the brain. All through, from diagnosis to surgery to post-surgery, hope remained a constant but its face kept changing. From hoping that the tremors would be non-worrisome, to thinking that the surgery would have no complications and to assuming that we’d be back home in 15 days. Ira’s treatment in the hospital lasted for 2.5 months. A major brain surgery and several post-operative complications later, Ira was in a state of poor consciousness. She had lost her speech and her ability to register and respond to stimuli around. In medical terminology, she was in a vegetative state. With each passing day, hopes of her recovery diminished. Our hopes for cure and recovery changed to hopes for comfort and relief for Ira. Help to hope rightAs a mother who went through it, I think there is confusion about hope during palliative care. It is not about giving and keeping false hopes about recovery or cure. Although, in our case, the acceptance of Ira’s condition took time to settle in, we learnt to keep any false hopes about her recovery at bay. We need to understand and accept the prognosis and course of treatment. There is no need to dismiss or discard hope. It just needs to be realistic. Focus on short-term goals and expect practical outcomes. Right through her palliative care, with all our love and compassion, we worked to provide as much comfort at home and as much relief from her neurological problems as possible. If a terminal patient or family member makes long-term plans or envisions a future with all, it is important for the medical and allied professionals to gently help them understand the prognosis. And tell them what hopes that they can realistically harbour. Hope beyond cureHope in palliative care, as complex as it may appear, is about several aspects except a cure. It should be about a good quality of life in the time left, reconciliation and closure with family members and friends, avoiding discomfort during the care, and being cared for with utmost love and selflessness. Though the tragedy of loss and the grief of death always stared us in the face, our family was content that distressing symptoms were reduced and managed at the earliest. As her mother and caregiver, I felt that Ira’s troubles, malaise and anguish were far greater than mine, and this gave me the strength to keep going and to care for her with even more compassion and love. Yes, hope is intangible. It will not just bounce into your life and light it up like fireflies at night. Find it within. Hang on to its threads as if your life depends on it, because it really does. Pratima Mehta writes a blog about Ira’s journey, how the family coped and practical aspects of care. ALREADY PUBLISHED IN THIS SERIES This story is about Madhav and Eknath (both about 75). Two different men and their families, who do not have much in common. Except for a common villain, dementia. This story is about how palliative care is helping them cope. I started looking after Madhav following a phone call. “Can you help my mom? My father is a dementia patient. My sister and I live out of India. My mother has difficulty managing him. Can you make home visits?” With Eknath too, the starting point was a call. However, the caller was clueless about the diagnosis. “Can you help my uncle?” Sure! What sort of help? “I don’t know. I need your guidance.” "Why can't he behave?"Both Madhav and his wife have chronic medical conditions. He has dementia and heart issues. She has kidney problems, diabetes and blood pressure. Their daughters who live abroad try to manage things remotely. There is no other family support. The first thing the wife told me was, “He does not remember anything, does not want to do anything and doesn’t co-operate. I don’t understand why he is doing all this to me. Why can’t he just behave properly? He was okay until a few months back.” “You do know that he has dementia, right?” I tried to make that question sound as gentle as possible. “Yes, I know that. That is okay. What about the other things he keeps doing that trouble me?” Would prefer to, but can't be aloneEknath is unmarried. He was a professor in a small town, lived alone, self-sufficient. He has always been on good terms with his siblings and their children. No longer working, he was keen to spend the rest of his life in that small town that had been his home for so long. But fate had other plans for him. Worried by his repeated falls at home, his neighbours requested his nieces and nephews to take him to a place closer to them. Thus, after 40 years, he ended up in the big city of Pune. Investigations suggested the beginning of Parkinson’s. One of his nieces volunteered to accommodate him in her house. But he was not comfortable there. He did not want to be an extra burden as his brother was already a Parkinson’s patient and needed constant attention. Eknath became aloof and would not co-operate. They decided to let him to stay separately, with someone visiting him frequently. This arrangement lasted for a few months. However, as his symptoms worsened, it became difficult. When I visited him, his cognitive abilities were intact, he could recognise people and he was alert. Helping the spouse copeIn another part of Pune, as I started working with Madhav, I realised that many of his cognitive abilities were affected. He could not comprehend what he was reading, nor could he complete any activity on his own. But I decided to make the wife my first priority. We had a few issues in the beginning, but I managed to develop a good rapport with her by and by. I had to make her understand the whole spectrum of dementia and how to cope with his behaviour. In the course of our conversations, I discovered that apart from watching TV and playing solitaire on the laptop, she could draw well and liked to solve word puzzles. She did have some drawing material lying around but those were in a bad shape. She was not very keen to spend on her hobby, but I persuaded her to get some new stuff and arranged for some puzzles. Soon, she got going and was happy in her own space. "This is an invasion of privacy"In the case of Eknath, it took some coaxing before Eknath agreed to employ a caregiver for the day. “I don’t want anybody in the house, I can manage myself,” he was still the proud, independent professor. Eknath had not been to a doctor for more than two years. I suggested a visit to the neurologist. Tests confirmed early dementia. Marking a new phase in his life, Eknath started taking medicines and slowly got used to the caregiver. There were more falls and serious issues with hygiene and nutrition. The caregiver had to start staying nights, too. “This is an invasion on my privacy,” Eknath protested. We were all helpless. We pleaded with him to try it out for a few days. He agreed reluctantly. I helped set some rules and regulations for the caregiver, who had had no professional training. I also used my weekly visits to build a good rapport with Eknath. We would do a lot of activities together—games, puzzles, drawing, painting, craft work and so on. They all cared for him, but the nieces and nephews could not spare too much time from their respective lives. Except for his siblings and some old students, he had no social visitors. Life appeared to be under control. Boosting the support systemMeanwhile, Madhav was having his good days and bad days. Did they have any doctor on call to help them out, in case …. No! Any relative? “Well, I have a cousin. She is old. But she can come when needed.” That did not sound very promising. I was constantly in touch with Madhav’s daughters. They arranged for a local doctor to come home and guide them. We also managed to locate a younger member of the extended family, who was willing to come whenever Mrs Madhav needed any help. I gave them a few tips on making optimum use of the support system now in place. When to call for the doctor, when to hospitalise, how to manage the caregiver and so on. I helped them prepare their home for the long-time care of a dementia patient—caregivers, Fowler bed, essential medicines. I also got them to involve a step-down centre where he could be admitted for symptom management. They also engaged a palliative care physician. I involved the family in long discussions with the experts—what to expect, likely difficulties and how to manage those. “How do you want your father to be cared for?” I asked both the daughters. “Do everything possible,” one said. “I want him comfortable,” said the other. Two different perspectives. As it happens very often, I knew this conversation would be long and slow. “Where do you want your father to be? At home or in a hospital?” “Home, of course.” Mother can manage him best at home. Initially, the daughters were unsure about involving the mother in the discussions. What would she know? Well, she surprised everyone. During the discussion with the palliative care specialist, Mrs Madhav clearly demonstrated she was now assessing the situation objectively and was ready to cope with comfort care. Both the daughters also concurred that comfort and quality of life were important. All these discussions got the daughters worried. “Is father so ill? Should we come down to see him? We want to be there when he is really bad and when mother needs us most,” they told me. “I understand that,” I told them. “But how about coming now? When your father can still recognise you? You can spend quality time your parents. You will always cherish those memories, whatever the future holds.” A turn for the worseOne day, Eknath had a nasty fall. That necessitated a surgery followed by another. Old difficulties like incontinence, hygiene problems and behavioural issues started worsening. A local doctor was arranged to take care of his physical symptoms . Meanwhile, the need to provide constant care day and night took a toll on the caregiver. He suffered a burnout and the quality of care dropped. It was time to look for a more lasting solution. That triggered a debate among the members of the family. “Why not keep him in an assisted-living centre? He will be well cared for.” “But for how long?” “Maybe he should move back to his hometown? That’s what he wants.” The discussions went on until they decided to keep him in a centre under medical supervision. Peacefully ever afterThe journey continues. Madhav’s daughters have already come home more than once and have spent time with father. As he continues to move away from them in body and spirit, they are more in control of what is happening. Mother and daughters are more at peace. At the centre, Eknath’s health has improved slightly. They have started him on physiotherapy. There are people around he can interact with. At the request of the family, I have been regularly visiting him at the centre. He repeats one question, “When do I go home?” Are you not comfortable here? “Yes, I am. But I want to go home.” Eknath’s family and well-wishers are still discussing. There are some tough decisions to take. Everyone means well. Everyone wants a say. Except for their names, Madhav and Eknath are for real. They face difficult questions and the answers are not easy to come by. As dementia worsens, palliative care will help them remain free from pain and distress. Until .... Until and after, science and compassion will continue to help them all cope and find peace. Madhura Bhatwadekar, Palliative Care Social Worker ALREADY PUBLISHED IN THIS SERIES When I met her the first time, she was on a wheelchair, in severe pain and was being treated for pancreatic cancer for nearly three years. Her husband, her primary caregiver, was with her. I studied her papers and examined her. I asked her if her ascites (fluid in the abdomen) was causing her discomfort. She was willing to manage. The next contact was about 12 days later, when the husband called. She had been recommended an MRI. He asked me if it made sense to push her through yet another MRI. Then he came over to talk to me . Their two sons were abroad. Financially, they were comfortable. They lived on the fourth floor and the building had no lift. Every hospital visit meant maneuvering her down the stairs. He was willing to do that. But to do that every time? Won’t it be difficult for him to manage her at home? Dealing with at-home careI briefed him about the potential challenges of at-home care. Perhaps it was time for him to have a frank conversation with her doctor about the prognosis? One week later I got a request to visit the patient at home. The doctor had said that her treatment was now at a palliative phase. Thanks to that, the husband had a better idea of my role as a palliative care doctor. I examined the patient. It was obvious that her disease was progressing rapidly. She looked jaundiced. No, she still did not want her ascites to be drained. She looked at peace, pretty even. She had just one fear. Occasionally, when she got up, she felt as if she was about to fall. Now that I was with her, I encouraged her to try and get up. With my help, she did. She was stumbling. It was clear to me that she was wobbly. After safely putting her back in bed, I suggested several measures. She was not to be allowed to get up and walk without support. Never. And she needed a hospital bed with rail guards. His brother walked with me as I took the stairs down. He was not sure if the sons had the correct picture. I suggested he could share my number with one of them and I would be happy to brief them. He was relieved. That evening, before I could speak to the son, I got a call from the brother. The patient had had a fall. They had rushed her to the ICU in a nearby hospital. Spend time together nowWhile the immediate injury was being taken care of at the hospital, I got a call from the son in the US. I briefed him fully and answered his questions. He said he was coming to India towards the end of the month, three weeks away. If he wanted to spend some quality time with his mother, I suggested he should reach sooner. The next call I received was again from the same son but after he had reached the hospital in Pune. He had met his mother and she had recognized him, smiled at him. He was happy. A couple of days later, the husband’s brother called again. She was not doing well at all. The second son too was on his way. He too got to meet mother, but she was already on ventilator. The family had a discussion with the doctor. How long should she remain on the ventilator? The sons decided to wait until the next evening. But she did not wait. She passed away the next morning, in the ICU. If only ...A few days later, the son spoke to me. “We knew her disease was serious. She was so keen to be at home. Dad was trying to make it possible. I desperately wanted her to get comfort care, like what we get in the US. Then after all those months of suffering, she got to meet you. Thank you for asking me to come down sooner than I was planning to. I got to meet her, spend some time with her.” He was sobbing bitterly. I told him that all I did was try to make the journey smooth. For the traveler and her dear ones who were around to see her off. She was gone. But those moments together, those memories would stay. When it comes to a terminal condition, is it possible to prognosticate the end with any certainty? Would the ending have been less painful for all, had there been franker conversations sooner? Could they have then made better use of the time with her? Dr Priyadarshini Kulkarni, Palliative Medicine Consultant, Pune. Founder, EaseandSupport ALREADY PUBLISHED IN THIS SERIES These days we have several days dedicated to one thing or the other. Tomorrow, October 12, 2019, is earmarked for something that concerns life and death, the comfortable, dignified transition from one to the other and life thereafter. The second Saturday of every October is World Hospice and Palliative Care Day. Unless you catch a stray headline or a post brushes by while you wade through social media, you may miss the significance of October 12, 2019. Unless you suffer from a chronic illness or you care for someone who does, or you help both as a palliative care professional. In which case, it is a day that would probably mean the world to you. This is the right occasion to remember two women who were strong enough to be compassionate. They were both discouraged from the medical profession when they started their education. Then the world plunged into war and they boldly went into the uncommon profession of compassionate care. They deliberately chose to sit next to and hold the hand of pain and misery. So that they could teach an uncaring world to understand and manage both, and death, better. Meet Dame Cicely Saunders and Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, the Pioneers of Compassionate Care. Dame Cicely Saunders |

| Adapted from an article by Patricia Ricci-Allegra, PhD, RN, CPNP-AC/PC in Medscape. |

Those dreams were his motivation to work hard and long.

However, by the time I first heard of him, Muthu was no longer a florist. When you are confined to bed with a damaged spine and advanced cancer of the lungs, there is very little that you can do. Except hold tight to those dreams, worry and wait ….

At the "abode of compassion"

“I have never done any harm to anyone. I have no bad habits. Why did this happen to me? And what will happen to my family after me? My wife is so innocent she does not even know how to make a phone call. How will my daughters continue their education? There is no one else who can help them,” Muthu would go on and on.

After Muthu was admitted early September 2019, the immediate aim of the care team was to keep him comfortable, free from pain and distress. “As the counsellor, for the first couple of days, my job was to let him vent. As professionals, we know about the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. That tough journey is for the patient to undertake. We can only offer a comforting hand and an empathetic ear.”

Helpless, but reluctant to burden others

As radiation therapy started, they hoped for the best. And kept their daughters in the dark.

What landed him in bed was not the cancer, at least not directly. He was travelling by auto-rickshaw when a bad bump on the road gave him a sudden jolt. He was in too much pain to move. The doctors at the hospital, where he was rushed, discovered a ruptured disc. The surgery that followed made it worse.

Two weeks after cancer was diagnosed, Muthu found himself at Karunashraya, limited to the bed and staring at an uncertain tomorrow.

A few days after the admission, the nursing staff observed that he was hardly eating anything. Was there a problem that they were missing? Sundari asked him.

“You see, the nurses here are all as young as my daughter. If I eat, I will pass motion. How can I make them clean me up? It is not right. I would rather not eat.”

Muthu relented only after the nursing team spoke to him, at Sundari’s request.

Relieved that family is cared for

“We got one of his cousins to stay with him. That helped to lift his mood,” Sundari said.

Karunashraya tapped into its vast network of benefactors. Funds were soon in place to ensure that the girls would complete their education. The shy housewife started attending free classes in tailoring and embroidery.

“I am sorry I am troubling so many people. You have no idea what a relief it is to know that I do not have to pay for all the care you are giving me. And then you have made sure my family will not be in the streets after …”

His worries about “What after me?” addressed, Muthu greeted Sundari every morning with a resounding “Good morning!” Unfortunately, the sunshine did not last too long.

Muthu passed away in his sleep on September 21, 2019. His wife who was with him until a few hours before the end, remembered his request: “Please take care of our daughters.”

Karunashraya made it possible for him to take leave peacefully, relieved and with dignity. His family would always miss him. No one can ever love and care for his precious family as much as he did. But, with Karunashraya backing them, they are determined to fulfil the dreams he had for them.

We violate and eliminate those who are not like us or whom we do not like. Because we can.

Rivers are being ravaged and smothered. Hills are being bulldozed flat. Trees are going up in smoke.

Patients are being exploited; doctors beaten up.

Aren’t these symptoms of a world that is cracking? Compassion is in crisis.

Compassion is what makes us human. It is what makes us love and respect everything around us: human and non-human, animate and inanimate.

This October, we shall talk about one facet of that compassion, from the realm of medicine.

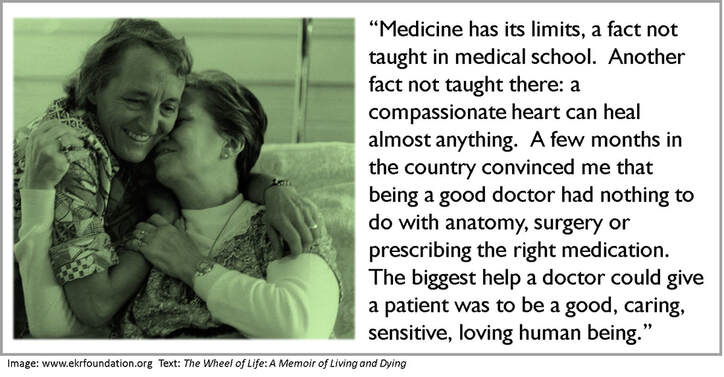

Palliative medicine (what I prefer to call compassionate medicine) too is born in the textbooks and draws on science. Yet, it is also the discipline that accentuates the inexact dimension of medicine.

Palliative care is about human intangibles like comfort, peace, solace and compassion, too tenuous to fill a syringe or a capsule. It often prescribes a listening ear, a sympathetic hand or mere silent presence in person to light up lives darkened by grim prognoses.

Stories of lives that moved on. Of lending strength to cope with the loss and go on.

Of blurring boundaries between cold science and warm emotions. Of skepticism transforming into spirituality.

Do you have a story of compassionate care (or the lack of it) to tell? Please share.

Disclaimer: I am not a medical professional. Nor am I an expert in palliative medicine. I do love to tell and share stories of compassion. And I would love to hear your views.

The second Saturday of every October is World Hospice and Palliative Care Day.

Author

Vijayakumar Kotteri

Categories

All

Book Extract

Cancer

Community Support

Compassionate Care

Covid 19

Covid-19

CSR

Customer Care

Death And Life

Film-based

Musings

On Communications

On Writing

Organ Donation

Pallitiave Care

Stories On The Go

Unseen Faces

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

August 2021

April 2021

September 2020

August 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

January 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

August 2019

June 2019

May 2019

October 2018

September 2018

September 2017

July 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed