|

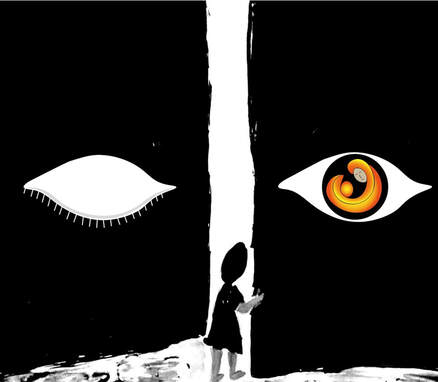

Four-year old Gulab was at a busy railway station with her father when someone came close and stabbed him. As he lay dying, and as the world around them rushed about its business, she quietly shut the world out. All I knew was Gul was a puzzle and one of the problem cases when I took charge of her and a bunch of other children at the orphanage, where I used to work. Her face would always be blank. No expression at all. Normally, we would quickly know every new child’s likes and dislikes. Gul had been around for weeks. There was no sound, ever. We had to anticipate everything—from washroom breaks to food to even a few sips of water. Once the background story sunk in by and by, I knew that more than psychology, Gul needed to reconnect to love, to belong to someone. Long before he was killed, her father had been the only one for her. Her mother and a sibling had gone away after some family dispute. Being there for GulI started giving her extra affection. I would be with her every possible moment of the day. She would go to sleep on my lap. Whether she responded or not, I would keep up a chatter with her. I would laugh and not bother about her response. I could sense her eyes following me. There was no expression on her face, but her eyes would be on me and would tell me a lot—sorrow, helplessness, loneliness, frustration, depression and so on. Later, she was comfortable enough to put her hands around my neck. Those hands would transmit her unspoken words, her fear, her worries and, simply, her need of a hug and lots of love. She used to wait for me, and her eyes would follow my every act until I finished with the other children. Then I would take her in my lap, hold her hands or kiss her. Others in the orphanage were getting sceptical. I ensured that I did not neglect any other child in my care. Just that the physical and emotional attachment was strongest with her. Though there was no reciprocation of any kind. Depending on the weather and the time of the day, I would often take the children to the terrace. There we had books and drawing materials. I would read them stories. We would draw stuff and sing songs. When playtime was over, all other children would rush down on their own. Gul would stick around until I took her down. That day, the children had run down. I was putting the books away. Gul was there too, as usual waiting for me. Suddenly, I heard a little voice behind me: “paani …” I dropped the book and turned around. Gul was looking at me. She repeated, “paani…”. I grabbed her and kissed her wet eyes. I was laughing and crying. I crushed her to me and just didn’t know what to do or say. Sometime later I carried her down and excitedly shared the news with my colleagues. Gul had spoken. She had asked for water. They had difficulty believing me. Because Gul had clammed up again. Opening up to loveGul started changing. It was slow. She would continue to cling to me. It was quite a task to get her to accept the other “mothers” in the orphanage. Gradually, Gul was as normal as she could be. The day she was taken away by her adoptive parents, I was not sure if I was happy or sad. I was not around to wave bye to her. Maybe it was better that way. Months later, someone told me that Gul was paying us a visit with her parents. I was thrilled. This time I was determined to see her and talk to her, even if she did not remember me. I was in one of the inside rooms and saw them get out of the taxi. Gul was looking taller and prettier. Suddenly, I noticed a change in Gul’s expression. She was looking at the building and it was as if a cloud had passed over her face. I was all set to rush out when I stopped myself. Did the place remind Gul of the dark days of her life? If she were to see me now, won’t it be worse for her? I remained hidden and moved to another part of the building. Far away, I could hear the supervisor calling out for me. I ignored that and moved towards the terrace. Maybe an hour later, I could hear them getting ready to go back. I peeped out carefully. Gul appeared to be happy. Yet, I sensed she did not want to look back and was in a rush to get into the taxi. I waved out more for myself than for her. Once again, I was crying and laughing. Then I gathered myself and went down. There were other flowers needing help to bloom. Based on a true story narrated by Vaijayanti Thakar. Some details have been changed to protect privacy. Art by Shravani Panse.

8 Comments

One of the privileges of being a writer is meeting people like Vaijayanti Thakar, whose work is to connect, heal and, simply, love. Recently she remembered an unforgettable Holi celebration. The month of March 2021 ended with the festival of colors, Holi. Traditionally, it is a time for people to come together and color one another. But this year the virus did not allow that. It kept revelry at a forced, colorless distance. My friend, Vaijayanti, whose lifetime work is to care for others, shared the story of a different Holi celebration—with a group of blind girls. Holi with those who see only blackSome years ago, she used to handle the corporate social responsibility (CSR) function of a company. When she invited volunteers to join her to celebrate Holi in an institution that cared for blind girls (some of them had limited vision), there were questions galore. Is that a joke? How do you celebrate colors with someone who can see only black? How do you even spend three hours with them? “When we arrived, the girls were all in their uniforms, sitting in a neat row. I asked them if they wanted to just sit there or play. They were immediately up with great enthusiasm,” Vaijayanti remembered. She reminded her colleagues that everyone there had the same inner vision. It was just a question of letting go, of accepting, of sharing love. They started with balloons. “Someone whispered a doubt. Can you blow a balloon without seeing it?” You can and they did. The inhibitions began to crumble. The balloons made all of them little children again. They sandwiched a balloon between one person and the next and made giggling trains that went on some merry trips. Not once did anyone fumble, touch the balloon or lose direction. They were too busy enjoying the journey. Letting in, letting outBack in the room, it was time for a fight with the balloons. It was the time to truly let go. There were several displays of aggression and anger. The black within was yielding to color. The balloons were harmless, but somehow, they were powerful in drawing out the deepest feelings. “Then we held hands and went round and round. It was a time of connection, of reassurance.” Out came the colors and the musical instruments. It was clear that art did not require perfect vision. And from chaos can emerge some wonderful music (again requiring more instinct than sight) that touches the heart. “Those were a few short hours. We gave and gathered a lot of love. Often the canvas before our eyes is washed black, but everyone has a rainbow inside that is just waiting to come out.” Before they reached that place, everyone was going on about blind girls. “When we left, blindness did not figure either in our conversations or in our silence.” “Everyone has a right to love and be loved. It just takes effort. We were all lost in the little effort that we had made and what more we could do if we just let the colors enter our heart." Images: Shirish Ghate. +91 98230 18328. [email protected]. Insta: sigafotopune

|

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed