|

It was to be another night of work, another set of passengers. But it turned out to be a long, unforgettable nightmare. Here is the story just as the cabbie told me. I drive this cab mostly at night.

That night I picked up this two women from a posh locality in Pune. They looked short on dress and high on alcohol. I would later learn that they were college students. One sat next to me in front while the other settled at the back. I wonder if it was the AC or the movement of the car that triggered it. Suddenly, the one in front threw up in the car. Almost at the same time, the other one also threw up. Then they were both out. The stink was very bad. And I didn’t want them lolling about. So, I stopped the car. Used the seat belt to ensure the front one was securely packed. Did the same to the one at the back. It must have been after midnight when we reached their destination, a hostel. The security guy took one look and refused to let the car enter. “Show their IDs.” “It is too late for inmates to be allowed back in.” I didn’t like the way things were shaping up. Fortunately, there was a police station nearby. I took the car there and explained the situation. In a jiffy, the cops turned the story around. Suddenly, I became the prime suspect. Where did I pick them up from? What did I do to them? After a lot of pleading, they let me go. The women are your responsibility. In case we hear of any rape, we know whom to book. So, I drove some distance away and stopped the car. There was half a bottle of vodka and pack of Marlboro lying next to one of the girls. I picked up both and locked up the car. Whenever they woke up and tried to open the door, I would know. I called up my service provider. Explained the situation. Two executives turned up—a woman and a man. When they looked inside, I could see the woman executive trying not to puke. They requested me to stay with the car and the women. They would ensure that I would not land in any trouble. Plus, they promised compensation. Then they left. I sat a little a distance away, by the road. Finished the vodka and the cigarettes. I thought I deserved that for all the trouble I was in. After some time, the car alarm went off. They were up. “Are we safe? Where are we?” They were not out of it yet but at least they were conscious. I explained the situation to them and assured them that they were safe. They were very apologetic. Then they asked me to take them to a resort a little distance away. It was almost morning when they got out of the resort. When they did, they were clutching two bottles of alcohol. Both were drinking all the way back to the hostel. They got out and again apologized profusely. I said I had suffered a huge loss thanks to them. One of them asked me “how much”. The fare itself was nearly 3,000. Plus, lost business while I was babysitting them. Plus, more potential lost business while the car remained at the garage getting a thorough cleaning. “Maybe about 9 or 10,000,” I suggested. She went to the ATM. Came back and gave me 14,000. I pleaded with them not to drink so much. They were lucky they were in Pune and not in Delhi. They promised they would take care. I never met them after that.

5 Comments

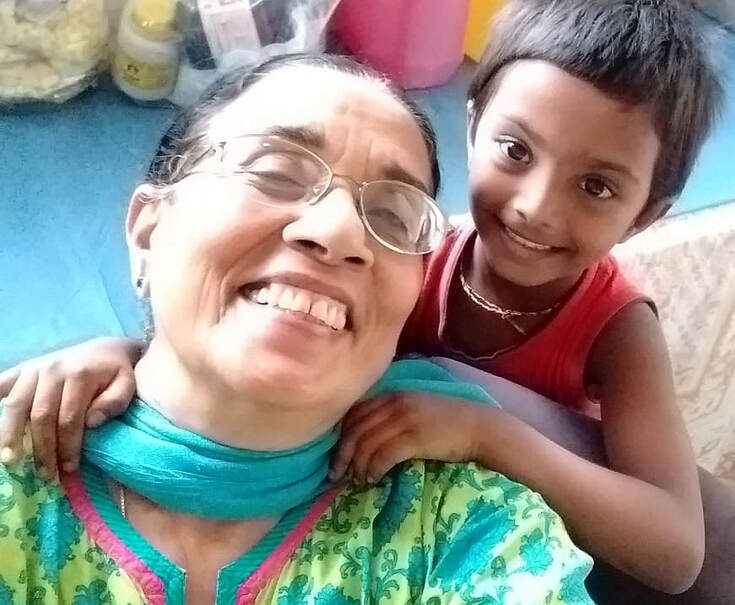

THE UNSEEN FACES SERIES 6. DR KHURSHID BHALLA I reached the hall a little late. Given that it was the first annual day celebration of “doctor foundation”, I expected to disturb the speech of some important physician, while the other doctors on the dais frowned at the latecomer. Instead, I found a lovely dance by children in progress, all energy and rhythm. Then came another, where the young choreographer (“a volunteer” the emcee said), was also a participant. Distribution of certificates to those who had completed a beautician’s course (“conducted by an employee”) followed. As I began to wonder if I was at the right venue, I looked around at the audience. They were mainly children, all dressed for a special occasion. They were restless and happy, with my immediate neighbour bouncing up and down on his seat, enjoying the music. He looked at me as if asking why I was not joining him in the celebration. The lone photographer was having a difficult time protecting his tripod from those constantly running to a better seat. Just then, the person who had invited me appeared on the stage. The applause told me she was a favourite of the audience. After all, she was the popular “Bhalla Madam”— Dr. Khurshid Bhalla, Founder Trustee of The Doctor Foundation. Facilitating the miracle of birthYoung Khurshid was always sure she would become a doctor. Her father, the late Maj Gen Dhunjishaw Doctor, had served as the Commanding Officer of a number of military hospitals across the country. That exposure, and her love for children presented paediatrics as a good option. Until a child’s death made her change her mind. “During my internship, I happened to witness the death of a child who had been admitted to the hospital just four days previously. I was shaken up by that death. To me, it was grossly unfair that such a small child should die, even when he was undergoing treatment in a hospital and the paediatrician on duty was close by,” she remembered. She turned to gynaecology and obstetrics. “I thought I would be happier dealing with birth. For me, every birth remains a miracle.” Dr Khurshid Bhalla, now 65, retains her love for children, though she has not helped deliver a baby for several years. Instead, at the helm of The Doctor Foundation (named after her father), she is today on the threshold of a new era in community care, going beyond medicine. Unfit for the business of careShe had the option of working with a private hospital or setting up her own clinic. Yet she has spent most of her life working for charitable organizations. Why? “It is not that I did not try,” Dr Bhalla explained. “I did set up a small clinic in Pune. There I would carefully examine the patients who came, hear them out and then prescribe the test or medicine that they required. I would charge about ten rupees per patient. I thought it was my duty to help the poor and serve them at a price they could afford. I was naive enough to think my model clinic would help a lot of people in the locality. Instead, they simply stopped coming. And my nurse, who was my assistant, told me unless I started giving injections and tablets, no one would come. So, that was that. Obviously, I was not cut out for the business side of care and I could not afford to keep the clinic open.” In 1996, she joined Care India Medical Society, a trust that provided a social support system in the prevention, early detection and terminal care aspects of cancer management. “Care India’s clinic where I worked was surrounded by homes of the underprivileged. HIV infection was rampant. A few years after I joined, I came across many HIV patients and their families,” Dr Bhalla remembered. During those years, HIV infection was almost a certain death sentence. Many mothers lost their children; young wives their husbands. “I would visit the women at home and try to help. Some NGOs came forward to adopt some of the orphaned children. There was one shelter in the outskirts of Pune that took in HIV patients. They had zero facilities. Often the watchman, out of compassion, would bring rice and dal from his house to feed the patients.” It was quite common to simply abandon HIV patients on the streets. “I heard many horror stories of patients curling up on the road all alone. When they vomited or had diarrhoea, they would drag themselves a little away from the filth, helpless and miserable. I knew this was cruel reality and not just fiction, when I heard a social worker casually announcing how she had abandoned her husband, who was in the final stages of AIDS, outside their house before she came to work.” Serving the imprisonedAs part of Care India’s work, Dr Bhalla used to visit Yerwada jail in Pune to examine women inmates. “The jail authorities were surprised that I mingled closely with the women. For me, they were simply human beings who needed care. Some of them were overcome because someone from ‘outside’ was willing to touch them, talk to them.” Dr Bhalla was shocked to learn that some of the HIV-infected prisoners, whose terms were over, refused to leave the jail. They would plead to remain in prison. “Where else would we go? Our families do not want us.” One ex-inmate settled under a tree a little away from the prison. The police decided to force the issue and took him to his house and browbeat the family into accepting him. After all, he was the owner of the house. That didn’t work. The next day he was back under the tree. Finding a new pathThen Dr Bhalla got an opportunity to extend her work in HIV. In 2004, she joined Mukta, set up by Pathfinder International, funded by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. She started work in Budhwar Peth, where most of Pune’s sex workers continue to live and work. “There were about 3,800 women living within one km radius. Initially as I tried to connect to them, I understood that they had the same story—mouths to feed. And as they put it, ‘after the first time, it gets easier.’” They did not want to be tested for HIV. “What’s the point?” they would ask me. “If we have the disease, we are going to die, test or no test. We would rather die without knowing.” It took a long time for things to improve. Things eased once antiretroviral therapy (ART) arrived on the scene. HIV infection was no longer a death sentence. Dr Bhalla considers the 10 years with Mukta a great learning experience in helping the community scientifically. “We had some of the best trainers working with us. For the first time, I found myself hopping into a bus and travelling to unknown villages to set up a network of clinics. I never considered myself a teacher. That stint taught me to be a trainer, to work with a team, to share the commitment so that more people could benefit.” After Mukta, Dr Bhalla returned to head the charitable chemotherapy unit of Care India Medical Society for a few years. Be compassionate, not emotionalWhen it comes to palliative care, the norm is “detached attachment”. You should be fully attached when you are there with the patient, but detach yourself later. This ensures you don’t carry a baggage of interminable worries, fears and sorrows home. “I know that I am a softie. But I can’t help being fully attached to my patient. Yes, I have been a victim of compassion fatigue more than once. But that’s who I am. I always say that I have more friends up there (in the heavens) than down here,” Dr Bhalla confesses. A 10-year old boy with cancer of the bone was Dr Bhalla’s patient when she was at Care India. He was the only son of a mother with three daughters. Once the doctors were discussing his case with the mother. After all the tests, they had concluded that the only option was to amputate the affected arm. They announced this to the mother. “They ignored the boy who was in the room with them. As soon as he heard the verdict, he jumped up and ran out, screaming. I was very upset. That was not the way to break the news. They treated the boy as if he didn’t exist. I was determined to make amends,” Dr Bhalla remembered. Despite warnings from her senior, she took personal responsibility for the child. “If he were my son,” Dr Bhalla told his mother, “I would try to save the arm.” She took the boy to Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai. There she found that there was a procedure to excise the affected portion and spare the arm. With the mother’s permission, Dr Bhalla got the surgery done in Pune. “I felt vindicated. The family was happy. But the joy did not last too long. The cancer returned. The boy was in severe pain. Then he died,” Dr Bhalla was distressed to recollect the case. “Finally, I understood why my boss was cautious. There had been a similar case where they had opted for the amputation. That boy was now doing well and was a regular participant in the NGO’s cultural programmes. It was a painful but necessary lesson. You must be compassionate, but being emotional can cloud your judgment.” Dr Bhalla regrets that compassion is largely missing today. “When my father was dying of cancer, several doctors were treating him and would come to meet him every day. He always looked forward to these meetings. Then they stopped coming. He would often ask us why they hadn’t come. Finally, the truth dawned. There was no treatment left for my father. What would they tell him? It was perhaps embarrassing to tell him that there was nothing more they could do. Looking back, I think even I failed my father as a doctor. Like the others, at that time I too did not know how to talk of death.” Caring for the communityIt is 2 a.m. The family has gathered around the bed of the dying elder. It is clear the end is near. The family has been prepared. Nevertheless, a call is made. After putting the phone away, Dr Bhalla gets ready quickly. Her scooter takes her to the house through empty streets, where “the stray dogs are my only companions”. She arrives and peace descends. She sits with the family until the end. She checks the patient one last time, leaves whispered instructions, consoles the family and goes back home. “This is something I have been doing for a long time. Many of my patients are the elderly or terminal. I spend time with them and the family. It is a privilege to be with them during the last moments. Nothing happens medically; a lot happens emotionally.” Is this a service under The Doctor Foundation? “Yes, it falls under my free home visits,” Dr Bhalla said. Walk into the Foundation’s clinic at Bhawani Peth in the evening and you are likely to encounter boys and girls learning to dance, young women learning to be beauticians, a tuition class and a couple of sewing machines that used to train would-be tailors until recently. Aren’t these rather strange engagements for The Doctor Foundation, headed by a medical doctor? “The Doctor Foundation’s objectives are rather broad, but the main goal is medical care,” Dr Bhalla explained. “We were registered in 2013 and started out with home visits in 2015. We started this clinic in 2016 and opened another in Kondhwa (another locality in Pune) in 2017. I am fortunate to have a team of doctors, mainly specialists, offering their services at the clinic on different days. The idea is to offer professional medical service at a nominal cost. Why should the poor be denied the service of a medical specialist just because they cannot afford it?” And the dancing children? “My original idea was a care and community centre for the elderly. We ended up attracting more children from the neighbourhood. In any case, once we finished with the patients during the day, the entire space was available. Why not put it to use? “An NGO donated sewing machines to teach the women in the community. Somehow, tailoring seems to have fallen out of favour, and so the machines are now idle. Then we had a part-time choreographer come in, keen to teach the boys and girls dancing. He is a big hit now! We also had an employee who was already qualified, volunteering to conduct a beautician’s course. Then a couple who takes tuitions free of cost for poor children asked me if they could conduct their classes here. So, we have a lot of young people coming to the clinic and, in my view, that really energizes the place,” Dr Bhalla said. That explained the dance performances I saw at the annual day celebration. “I thought it was a great opportunity for the children to showcase their talent. The money for hiring the hall was donated by a well-wisher. In fact, the Foundation has not spent on a single piece of furniture you see here. Some came from my house; others are kind gifts from various people. I prefer to spend only on essential overheads. The rest is all for the patients,” Dr Bhalla was very clear. Plans to do moreSo far, Dr Bhalla and her team of visiting specialists have cared for more than 5,000 patients across the two clinics. She is very keen that the Foundation does more. Her wish list for The Doctor Foundation has three main items. Set up a network of partner clinics. She wants to identify clinics that provide ethical, efficient service to patients and make them Preferred Partners of the Foundation. “I would like to begin with Pune and then spread to other districts.” Improve the home care programme. Recruit the minimum essential team and train them. “I have a couple of old cars lying around. I will be happy to begin with those.” Set up a hybrid home. “It will be a home for the elderly to begin with. Then I would like to add on an orphanage for children. I think the young and the old will provide each other very healthy company. It will be a happy home for both. They will not be just put there; they will want to be there.” Would the plans be commercially viable? “I am counting on cross-subsidization. Those who can afford to pay will get better facilities. In the process they will help us serve more poor patients. The service quality will be the same.” Dr Bhalla is positive her dreams would come true. Dr Bhalla is grateful to her fellow trustees for helping her set up The Doctor Foundation. “It has given my life purpose. I have a good reason to wake up every morning.” She also thanks her fellow doctors, the specialists who spare the time for The Doctor Foundation. “It is hardly remunerative for them. But they do it in the spirit of giving back.” Several hundred beneficiaries may not understand the intricacies of a trust. They are simply grateful that Bhalla Madam will hear them out and tell them what is wrong with them. They know she is on their side. And she always has the time to sit with them and hold their hand. … and they went back and lived |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed