|

A coincidence is a matter of pure chance. Except when the timing of the incident defies logic and forces a non-agnostic glance up.

In the movie I am watching with my wife, a rich grandmother resorts to unconventional means (like spraying pepper on those trying to help) to rescue her servant’s daughter. The girl is smart, and they had formed a bond from the time the little one started shaping alphabets from dough. Then circumstances trap the girl in a situation where she is exploited. Of course, her conditions are different from that of Sush. Yet, that girl in the movie, teaching other children to speak English, did remind me of Sush, the real daughter of a real servant, who used to work at our place more than a decade ago. Sush, then seven, did not think much of my teaching, the stories I told her and even outwitted me in the “spot-the-place-in-the-map” game we used to play together. I was about to ask my wife, if the girl in the movie bore some resemblance to Sush, when the doorbell rang. I paused the movie while my wife went to open the door. It was Sush! She had come with a box of sweets and a sweeter announcement that she had passed her grade 12 exams with top marks. We invited her to join us in the room where we had been watching the movie. The cloud of economic uncertainty continued to hover over her family, now larger with her little sister. Yet, her sunshine nature was undimmed. She hoped to become a Master of Business Administration one day. She had picked up a small job where she was by now “comfortable”, giving her enough confidence to master business one day. Yes, she spoke fluent English and was very comfortable working on the computer at her job. Those are important skills, I lauded her. No, she was not very comfortable with numbers—neither math, nor accounts. Yes, she knows it may not be possible to do only what she likes; and she must do it well, whether she likes it or not. I applauded her spirit. The 18-year-old sitting and talking to us barely looked bigger than the little girl we knew then. Yet, her confidence was several notches higher. While we were talking, I located the blog I had written about her. She stopped talking when she saw the image of the little Sush on the monitor. Halfway through reading it, she started crying. The tears just wouldn’t stop. When she finished reading and got her tears under check, I asked her why she had cried. “I remember everything. I was always so happy coming to this room, being here. I must have this," she pointed to the blog. "Please give me.” I shared the link with her. And assured her she was welcome to visit us whenever she wanted. When I wrote “At 45-minute school with Sush” I had never imagined that I would be spending another 45 minutes with her 11 years later. For a change, this time she agreed to do some homework. She would write about her memories of those years. Perhaps she would explain those tears and share some of her dreams? She may or may not submit that homework. But when we resumed the movie, it was difficult to unsee Sush whenever that frightened, English-speaking, fragile-looking servant girl came on the screen. The movie ended happily, showing the girl being cared for by those who loved her. She was set to live happily ever after. We are sure so will Sush. And that would be no coincidence. Because Sush writes her own script.

5 Comments

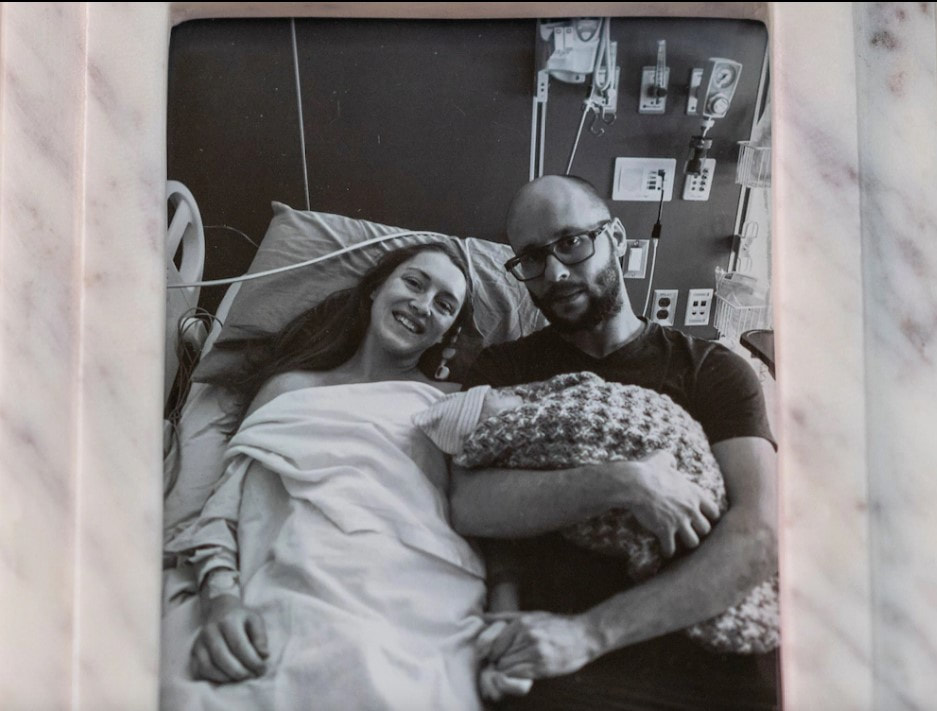

What does one do when the law that is blind to both medicine and compassion makes a mother carry a pregnancy though it is clear that the baby can only survive for a few hours? Baby Milo arrived in the world with no kidneys, underdeveloped lungs and a life expectancy of between 20 minutes and a couple of hours. He lived for 99 minutes. On March 3, 2023. Mother Deborah and her husband, Lee, had learned in late November that their baby had Potter syndrome, a rare and lethal condition. As long as their baby’s heart kept beating, the doctors would not honor their request to terminate the pregnancy. The new Florida law on abortion carries severe penalties, including prison time, for medical practitioners who run afoul of it. Everyone knew the baby would not survive. Yet, the parents had to wait for labor to be induced at 37 weeks. The Dorberts consulted with palliative care experts and decided against trying to prolong his life with high-tech interventions. The day before Milo was born, the Dorberts sat down with their son Kaiden to explain that the baby’s body had stopped working and that he would not come home. Instead, someday, they told Kaiden, they would all meet as angels. The 4-year-old burst into tears, telling them that he did not want to be an angel. After Deborah’s 12-hour labor, Milo turned out to be 4 pounds and 12 ounces of perfection, with tiny, flawlessly formed hands and feet and a head of brown hair. The obstetrician cut the umbilical cord that for 37 weeks had performed the functions Milo’s underdeveloped lungs and missing kidneys would now take over. Milo remained blue, swaddled in a blanket hand-knit by his great-grandmother. He never cried or tried to nurse or even opened his eyes, investing every ounce of energy in intermittent gasps for air. For 99 minutes that lasted a lifetime, they cuddled and comforted their newborn. At 11:13 p.m., a doctor declared Milo dead. At the service, the pastor from a local Lutheran church had a message for the congregation. “Not everything happens for a reason,” she said, echoing Deborah’s own rejection that the manner of Milo’s birth and death carried some special spiritual significance. Deborah wants other people to know what happened, how politicians intervened in decisions about medical care with a law that made doctors fearful of terminating even hopeless pregnancies. “If it helps another family or a mom, then good came of it because we’re all here to help one another,” Deborah said. “It’s not something easy to go through alone. You need all the support you can get.” I am not an expert in medicine or law. But I have a question for my compassionate friends in palliative care. How do you console, how do you care when law blocks your path, and medicine can only stand by? This is adapted from the report in The Washington Post. Please read the whole story here. Image from the report.

Last Sunday, the day the world celebrated mothers, was no different for this mother. Her two sons, 33 and 31, are growing without hunger, pain, joy or sorrow, thanks to her. But do they even know her? Sometimes they do in the dining hall what they ought to do in the bathroom. Or do in the kitchen what they ought to do out in the yard. Radhamani would discover after cleaning up the mess that the younger was down after another epileptic fit. She would rush to find someone to mind the elder son and then rush to the hospital to fix the wound. She has just one persistent sorrow. That they don’t know her, her love. Every moment, she pines to hear them calling out to amma. There are times when she is cleaning the vessels or sweeping the yard, that she would hear that call. She would look up eagerly, only to realize nobody had called her. Writing erases pain Writing offers her relief. When she writes, her sorrows get erased. She has already published three books in Malayalam. She had a small government job. Father was a sweeper at a bank. Mother was a housewife. After finishing his work, in the afternoon, her father would go to pick jackfruit leaves which he would bundle up and take to the market to sell. Her most cherished moments were when she and her mother joined him to help pack up the leaves and carry those to the market. Radhamani had to displease her parents when she decided to marry her childhood friend, Raj. Both families objected. But the couple stuck to their decision. Radhamani and Raj had their first son nine years after marriage. They named him after the poet they both loved — Shelley. Two years later was born the second son — Sherry. The boys were a little late to start talking. When Shelley was three and half, their regular doctor felt something was wrong and recommended admission to a larger hospital. Both children were diagnosed to be autistic. The parents were advised to pray. “I realized the truth that they would need my help to go through life. Gradually I regained strength.” Radhamani had no option. By this time, her father was dead. Radhamani’s family returned to live with her mother. When both of them left for work, Radhamani’s mother would look after the boys. “The boys would be at a special school until the afternoon. Then mother would feed them and take care of them.” Waking up to cruel reality Radhamani’s world collapsed when her mother passed away. That’s when she came to know firsthand how tough it was to bring up the boys. When the boys were 8 and 6 respectively, a heart attack claimed Raj. That shock haunted Radhamani for a long time. Now, it has been 25 years since he moved on. She learnt that the boys had no clue about death when the family went through Raj’s cremation rituals. They were in no position to do whatever they were expected to do as sons. That whole night Radhamani spent crying. “I know when I die my sons will forget me within a week,” Radhamani states calmly. “Yet when I go out somewhere, they would be waiting at home. Waiting in the hope that I would get something to eat. That waiting is enough for me to live on. Else I would have taken my life long ago.” Finding refuge in words People tell her death lurks in her stories and poems. Radhamani knows. “It is my writing that keeps the thoughts of suicide away. That is why my writing smells of death.” “After I die, someone should adopt my children. I hope the government opens a facility to take care of such children in every district. That is my appeal, my prayer. Then I can die in peace.” This is based on a report dated May 14, 2023, in the Malayalam newspaper Mathrubhumi, written by Sajna Alungal. Illustration based on images accompanying the story.

|

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed