|

A routine visit to the ENT physician resulted in an immediate admission to the hospital for “acute follicular tonsilitis with quinsy.” Now we move to the main story which is less about health and more about health insurance.

The estimate for claim clearly mentioned the admission was for medical management with surgery as an SOS option, if required. REJECTED: We don’t cover ENT surgeries for the first two years. The main treating physician takes the time to write a note explaining that the admission is for medical management and no surgery is scheduled. REJECTED: For the same reason by one person associated with the insurance company. REJECTED: For the same reason by another insurance company person, who was considerate enough to reduce the waiting time to 12 months. (In other words, if you are alive to seek treatment after 12 months, you might raise a claim again.) As the doctor expected, the patient recovers fast just with the medicines and is discharged on the third day. The patient pays and goes home. He has to work to pay the bills (including the health insurance premium). Believing that the amount would be reimbursed now (as it was only medical management), the claim is re-presented. REJECTED: “Patient paid and discharge.” Applause! According to your website, Care Insurance “is one of India's leading Health Insurance providers, with a claim settlement ratio of 95.2%.” Going by this experience, the numbers that constitute the 4.8% unsettled patients must be huge. Your marketing department is doing a wonderful job. But that is nothing compared to the astounding work of your Chief Excuse Officer. Refuse to settle for this reason and that until the patient pays and goes home. Then throw the masterpiece (don’t get distracted by the English): “Patient paid and discharge.” Bravo!

0 Comments

I love your washing machine. And I love your refrigerator.

Over the last two decades, when one got too old, replaced it with another from you. Again. And again. Loved the products based on actual use. Therefore, loved the brand. Except in the recent past. I understand old machines can breakdown. But then you have been so considerate to extend your care to your customer over WhatsApp. Or so I thought. “Please confirm your name.” I am presented a wrongly spelt version of my name. “Are you a dealer or a customer?” Huh? “Provide full address.” I do that. But must again reconfirm the LOCATION, the CITY, and the STATE. Yes, in all CAPS. “Describe your model.” “When did you buy it?” “This is out of warranty. You will have to pay X amount.” I have an AMC in place. “Provide details.” As I scramble to dig out the details … “Are you still connected? As I am not getting any response from your end I am bound to close this chat. Thank you for chatting with Xxxxxxxxx. Have a nice day!” Hey, wait! What about all those times you asked me to wait and vanished to do God knows what, while I held on. Three calls within a month. All following the same pattern. Technology is smart. Just from the mobile number, it can dig out all information including your last service request. That is the optimistic theory for the gullible. Tech must have a poor memory, though. Why else do I have to provide the same details in virtually the same sequence during every chat? Even if the chat is repeated within a span of 30 minutes? Of course, there must be a script at the other end that must be honoured. Who dares face the consequence of breaking the sequence! Until you buy, we woo you. After you buy, shut up and don’t bother us. If you dare complain, well, we’ll simply Whirl you, fool! What if there was an agency that could kill whoever you wanted at a bargain rate? The more you want dead, the less you have to pay. How long would your list be so that you can make the most of the bargain?

It was not easy for Peter, the central character in Neil Gaiman’s short story, “We can get them for you wholesale” to find an assassination agency. Finally, he found one and went on to have a meeting with one of the sales guys from the firm. Peter wanted to start with one guy in the office who he suspected was having an affair with the woman he was engaged to. Then the sales guy offered a two-for-one deal, just 250 pounds each. After some thought, Peter added the woman’s name. At their next meeting, the sales guy offered an even better deal—an irresistible bulk rate of 450 for 10. Peter took some time to think of the 10, “hunting for wrongs done to him and the people the world would be better off without”. It included his boss, the Physics teacher from school, an annoying TV newsreader and a neighbour with a yappy dog. After the list of 10 was ready, Peter was very satisfied with “an evening’s work well done”. He enjoyed the feeling of power he felt as he tightly clutched the list deep in his pocket right through work the next day. At the next meeting, the sales guy mentioned more enticing offers. Finally, irresistibly drawn down the path of better bargains, Peter asked how much it would cost to kill everybody in the world. “Nothing,” came the answer. “We’ve been ready for a long time. We just had to be asked.” Peter was mulling over what that meant when he heard cries all around and a soft knock on the door. Usually, I drop off to sleep after I complete a few pages of the book I am reading. After this story, I was wide awake, thinking of the people who might employ such an assassination firm.

They have been ready for a long time. And so many of us have already asked them. How long do we ignore the knock at our door? She had recently lost her job. Her family business was sinking. Her father had just been rescued and brought back home safely after yet another unannounced trip outside home, lost in the shadows of dementia. Her mother was struggling to take care of her own health even as she tried her best to look after her husband. And one of the many caretakers who joined and left, had walked away with all the savings of the family.

Then life became a song, several songs, for all of them, at least for a few days. It was not an easy decision, but the daughter decided to take on the additional responsibility of moving her parents to her own place. Steeped as the family was in music, it was but natural for all of them to gather around his bed and sing song after song and play antakshari. The change in the father was very visible. He smiled. Life returned to his eyes. His fingers remained rigidly curved but he would make an attempt to clap whenever he won the singing game. And he did win multiple times because he knew which songs to sing. The musical notes drove away their loneliness. No longer were they two bodies in another corner of the town that others were obliged to look after. There was no changing tomorrow. Today they sang. Then one night the father indicated that he wanted to go home to that lonely house where he lived with his wife. He was insistent. The daughter obliged. A late-night ambulance took them there. All the paraphernalia that had moved with them went back. Tired, the daughter decided to take it easy for a couple of days. Until her mother called. He had stopped trying to talk. Eyes closed. Not moving at all. The daughter rushed. Holding his hand, she called out to him. With great effort, he tried to open his eyes. Apparently, he recognised her. Just one word escaped his mouth: “sing.” And she sang. His favourite song. His face transformed. He was almost smiling. The next day he passed away in peace, at home. Life has pulled her back to its many inevitable chores and testing challenges. But she is unable to fill that gap. She knows somewhere he is listening. And applauding whenever she sings. So, she sings on. Nothing new in watching its film adaptation after reading a book, right? There is always a temptation to compare—was the book better?

The Netflix version of All the Light We Cannot See diverges from the book in many ways. Yet, for me, the book and the film were a compelling experience, each in its own way. When I started reading the book by Anthony Doerr, I found the treatment rather intriguing. Short chapters painting lives in two different parts of the world. Emotions co-existing with explosions. Empathy with enslavement. Two parallel worlds—one of a young blind French girl the other of a young German orphan boy, both dragged into World War 2. Until their worlds merge in senseless destruction not in their control. Apparently, Doerr took ten years to write All the Light We Cannot See, with most of those years dedicated to research on World War 2. Indeed, the book does leave you grimy, gasping and bleeding, as if the bombs just shattered the roof you were sheltering under. You too may echo the blind girl’s questions to her father in the film version: "Can you explain to me why a whole city is running away with nowhere to run to? Can you explain why the Jews are running the fastest? Can you explain why one country wants to own another?" It must have been a tough ask for Steven Knight (the writer of the serial) and Shawn Levy (the director) to adapt a story set in the early 1940s and published in 2014 to the sensibilities of the 2023 audience. I think they have done well. Both the printed and the filmed version throw light on the same fundamental question: what is the purpose of war regardless of which country you belong to, given that we are all fragile mortals? And for all of us, isn’t that light within, that none of us can see, the most dazzling? If we choose to see it? When I watched the series, I was already familiar with the characters, thanks to the book. Now that the episodes have shown me the sights and sounds of uncaring war and the uncared-for emotions of helpless human beings, I intend to go back to the book. I have a feeling it would be a different experience this time. Can revisiting locations where you once lived the moments that are now memories be therapeutic? How do you know which is better? Then or now? That or this? The two are different. You smile, you sob and even shudder. Then get back to what is. Shailaja, like her immediate family, did not think a few days in Vengurla would turn her life around. Yet during those days, she lived what could have been her life. She is aware of her dementia. And afraid of what it would erase next. I am grateful to the team behind “Three of us” for this unforgettable movie. And special thanks to Shefali Shah (really brought Shailaja to life), Jaideep Ahlawat (masterfully conveyed the joy and pain of a tantalizing return to a love he had given up on) and Swanand Kirkire (the caring husband confused by the apparent preference of his beloved wife for the past) for sensitively portraying the three central characters. Shailaja’s trip to the village she grew up in was a trip back in time to snuggle under memories for me too. The homes with semi-lit interiors, the well with the overgrowth, the vast open fields that I used to cut across to reach school and the almost-bare lanes where almost everyone knew everyone. Watch this movie, if you too would like to go back and hug your memories for a while. It may bring you more tears than smiles. Simply make the most of an opportunity for who you are to be with who you were. You may want to change the name of this movie from “Three of us” to “Two of us”— who you are, and who you could have been.  One of the telling sequences from the movie. Cajoled by her old dance teacher during a visit to the school, Shailaja joins a group of girls in their practice session. She starts well, then loses her moves. She leaves the group, backs away until she is almost hiding behind a pillar, as if seeking shelter from reality. Having been without a job (in the strict 9-to-5, on-the-HR-rolls sense) for nearly 30 years, it does feel strange when I occasionally encounter the question, “So, when do you plan to retire?” You mean I can be more retired than I am? Come to think of it, why should I retire at all? When The Economist recently echoed that question, I thought it would be fitting to put the retirement question to a few friends who are otherwise too busy working to answer my questions. The Economist column says most people don’t want to retire simply because they can’t afford to. Blame it on insidious inflation! Of course, some of the rich and the famous don’t want to because they don’t want to leave centre-stage. Where else can they draw the adrenalin from and get attention unless they are sitting behind that table day after day after day? Money mattersYes, money matters, tells my friend Lovaii Navlakhi, for the umpteenth time. He should know; that’s his job. If you started your job just last year, expect him to ask you next week if you have started saving for your retirement. You need to work for it, is what he says. He does not prescribe what you ought to do after your retirement. But he will run a stern eye down your investments and tell you what you need to put away if you insist on rounding the world. If the numbers say that’s an out-of-the-world possibility, he will gently point to the resort round the corner and remind you how much you can save by changing your goal. By the way, Lovaii has no plans to retire. Don’t ask me why. In the true spiritWhat I can tell you is why Geetha opted for early retirement from the bank where she used to work. She was part of the team responsible for reaching old age pension to poor, illiterate villagers. That experience exposed her to, in her own words, how the “other half” lived. When the first opportunity came up for voluntary retirement, she quit. And the very next day volunteered to work for a trust that provides ayurveda treatment and also serves the community around in several ways. Over the last 12 years she has been through it all—teaching the village women how to make chapatis to conducting odd-hour online meetings to raise funds to do more good for more people. “While I was in the bank, I was not seriously pursuing promotions. Now, given all the skills I have picked up here, I think I could have pushed to be the CEO of the bank,” Geetha joked. Geetha does not think retirement is synonymous with not doing anything. She is sure that’s the right time to reach out and help. Start at home. “It could be just sponsoring the education of your servant’s child.” Spiritually inclined as she is, Geetha is not too worried about the money part. A single mother, her daughters are settled and they had wholeheartedly supported her plan to leave the bank and take up community service. “What I have learnt is you should shed your ego. Keep yourself empty. Before you do anything, ask if it is for the larger good. Then go ahead and do it.” A different work codeUnlike Geetha, Siva has a long way to go before he attains the conventional retirement age. Yet, he too feels there is something spiritual about the idea of hanging up the boots (if that’s what software engineers like him wear). “Retirement,” he says, “is the time usually one could rest internally and, as the rush gradually slows down, one might begin to understand a lifetime of conditioning and its impact in terms of real inner peace and acceptance.” He accepts that it would be difficult to give up the skills that kept him fed all these years. But he is open to the idea of “doing the same thing differently” if only to derive satisfaction out of accomplishing some challenging work. He is clear that when he retires, he would not be financially dependent on whatever “work” he does. He hopes to save enough and then maybe “teach or mentor students from the underserved sections of the community.” This is his prescription for a happy retired life. Whatever your job or business was, “grooming ourselves to foresee and deal with the simple and common realities of life—health, contentment, forgiveness, acceptance and faith.” Helming a social causeSuprabha too is sure that she would lend her leadership skills for a social cause and not for a “corporate outfit” when she chooses to retire. She is some distance from retirement, but candidly admits that “my motivation has always been money.” In case she does not enjoy the work that delivers the money, she has a number of hobbies (partial list: running, trekking, biking, boxing) that keep her “adequately engaged.” Her motivation has always been to continuously upskill herself. So, what is her idea of retirement? “As time passes by, my ability to take breaks would increase. That's what I would call retirement.” And yes, she would love to be a nomad, not attached to a single place, and move where she would like to (preferably near the mountains). Peace in the bustleNo mountains for Umaya, though. He was born and brought up in a city and he would prefer to be in the midst of all the hustle and bustle and “yet retain my peace.” He is convinced that “or faculties remain sharper when we keep ourselves occupied.” That means you are unlikely to find him curled up in bed when the sun is at its zenith because he will be busy widening “the application of skills that I have gathered over the decades.” Now that Umaya has had his say, I have a confession. I had started writing this piece, confident that my friends would give me enough masala for something humorous. Instead, this is shaping out to be just the kind of boringly seriously work guaranteed not to upset the boss or a client. Very work like, in other words. More than a sipMaybe I should ask Jairam, who has always been my favourite Wodehousian writer, and who has just birthed his first book, Masala Chai for the Soul. His advice is not to retire if your job is your life and you have practically nothing else to do. Keep yourself involved in something for the sake of a timetable. It prevents you from drifting. “In the end,” he says, “runners easily overtake drifters.” He recommends picking up a job that is a mix of the old mixed with something sufficiently new. “That gets you to think anew.” “The mind is built such that it needs to dwell on something. An attractive dwelling place is your own aches and pains. A job gives your mind alternative pasture. Those aches and pains can wait. They may even reduce.” Not that I am an expert, Jairam, but that’s palatable philosophy without any masala. Don’t believe me? Listen to his parting advice. “The inconvenient truth is that our sense of self-worth is dependent not on who we are but what we do. So keep doing, keep living.” Maybe if I had caught him after he had just finished a cup of his favourite, he would have asked Jeeves to fetch his happy hat and then maybe, just maybe …. Too serious to relaxSomeone advised that I should speak to people from all age groups to gather a more representative view of what the world thinks of retirement. Well, the two youngsters I reached out to said they were too busy “working” to talk to me. One even went to the extent of suggesting that I was in the best position to write about retirement.

Such impudence, I say! Lasso these youngsters, Lovaii! Pull them in, deny them their iPhone 15 and make them suffer, I mean, save! Now that I have caught my breath, I am beginning to wonder. Is retirement serious business? As you cope with the hiccups of life, do too much time and not so much money combine with the looming full stop to reduce life to a sentence to suffer? What do you think? Whether you are on this side or that, pretty close or very far from the retirement fence, what are your thoughts on retirement? The to and fro Has eased But yet again We spelt it wrong It’s E-A-R Get the new, use it And hear hearts Here, there Close at hand Underfoot Listen To understand And respond Not echo The toxicity Let’s wear The new ear To truly hear Every chirp, rustle Whimper, sob And the loud hush With this ear Whether new or year Let’s just be Happy Image created using Microsoft Designer.

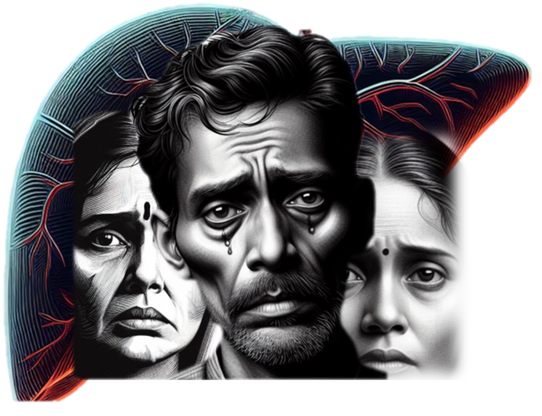

Wife: “Does it hurt now?” Husband: “How many times will you ask me? Now this pain will go with me. You take care of Guddi.” Guddi, 10, their daughter, is not very comfortable when he holds her hand. Wife: (Angry) And how do you expect me to do that? The wife accuses him of bringing this calamity on all of them because of his drinking. Guddi looks at both without any expression. Husband: “I wanted to help Sonu finish her college. Now I don’t know ….” The wife bursts out. Grabs Guddi. “And what do you want me to do with this one? Forget me. You are always more worried about your sister. Where is she now? Oh! My fate!” She slaps her forehead. Just then, the doctor walks in with Sonu, the sister. Seeing the sister, Guddi brightens up. Tries to run to her. Mother holds her back. The doctor examines the husband. Then says he has some good news to give. The sister is willing to donate her liver. The husband begins to ask something, but Sonu stops him. Sister: “Let the doctor finish what he is saying.” Doctor: “There are many reasons for liver cirrhosis. Some problems by birth, some virus. But in your case, we all know what the reason is ….” The husband holds his ears in apology and starts sobbing. “Never again.” Doctor: “Like I told you, no treatment will work at this stage. Only a transplant. That too quickly. Fortunately, your sister is a match. And she has agreed, and. Of course, there is no danger—" Sonu suddenly stops doctor. She addresses the patient, her brother. Sister: “The doctor says there is no danger to my life. He says he will take only a small piece of my liver. What I know is I am giving you a piece of my life so that you get a second life. Not for me. But for Bhabhi and Guddi. You were always worried about my college, right? Now you better get well. Because I want you to make sure Guddi completes her college. Remember, you owe it to me.” The wife gets up crying and does a namaste to her sister-in-law. She is unable to speak. Sonu enfolds her and Guddi in an embrace. In the background, the husband, weeping bitterly, does an apologetic namaste to the three. The doctor walks away. Guddi suddenly runs to him and pulls at his coat to stop him. Guddi: “Please don’t take too much of her liver. If you want more, take a little piece of my liver.” The doctor laughs and pats her head. Guddi runs back to the bed, sits, and holds her father’s hand. Her mother and aunt join them. Images by MS Designer Image Creator.

You wanted to walk with me, or rather, help me walk, didn’t you? You were even willing to push my wheelchair if I retuned in that state, weren’t you? The voice was familiar. Instinctively, I looked around. There was no one. Just darkness. I had stepped out for my walk earlier than usual. The streetlights were out, the sun wasn’t yet. Please don’t get spooked. I had also wanted to be with you. When they did not let me get away from the bed and all the tubes. And after. That’s why I decided to walk with you, just this once. Let’s just walk and talk. At least you do the walking, and we’ll think together. Sorry you had to be in the hospital for so long. The family tried their best to get you back. I am sure they did. But I had left me a few days before they took me out of the hospital. They just held on to the body. Were you in pain? After some time, it is no longer about me. It is about who is there, who thinks is responsible for me. What works for all. You may call it helping me fight. Or you may think it is torture by delegation. Would you have preferred to come home sooner? And do what? Trouble everyone at home? There everyone listened to what one doctor said. Here everyone would have been a doctor. You would run out of time and patience. Like it or not. And my journey would have just gone on, regardless. I flinched when they placed you on the hard floor. Then moved you this way and that to adjust the sheets and to place the things for the prayer. You were too much into the body that was no longer me. Suppose they took a call and took my stuff out of the body. Stuff someone else could use. Then moved what was left for the students to study. Would you have preferred that? Maybe that’s best for all? At least that’s what I am asking for in my will. Good for you. Take what you want and play with the rest. You know any time, now or then, what matters is if I am in you and you in me. In heart. In thoughts. Beyond rituals. Beyond expectations. But rituals are important. For generations. Respecting the memory. You are divine when you are no longer human. Strange! I could not place most of the people who paid obeisance to my body. Would they have come to feed me or even to just sit and talk with me before I had crossed over? And here they were, so solemn. Nice of them to come. Yet, somehow funny, thought. The sun is rising. Time for me to go. By the way, a sweet I used to enjoy a long time ago. I have been wanting to give it to you. Now that I have crossed the threshold, I can’t. Let me see. Then the blaring horn and blinding headlights of a wayward car broke the spell. The dawn was stretching and yawning. I would have dismissed it as a waking, walking dream, if my wife had not asked me after she finished putting away the veggies I had bought as usual. “What is this? Did you buy this? Or does this belong to someone else? Looks like some sweet.” Image by kordula vahle from Pixabay

|

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed