|

Dear Sarang,

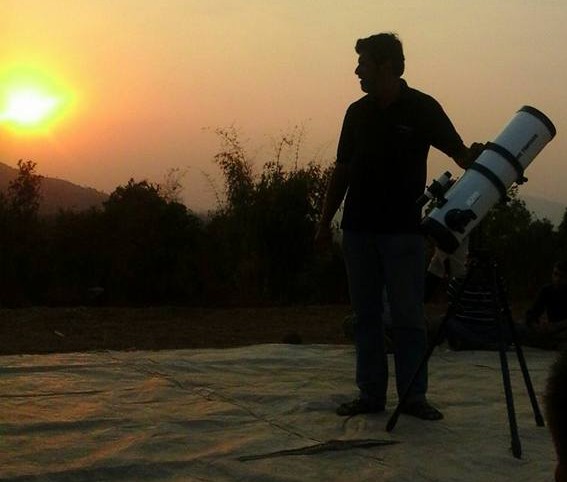

When you invited me to participate in the Messier Marathon Mania, I did not understand why. I am not into marathons, messy or clean, and neither of us is maniacal. Then you explained that “mania” was just a marketing appendage to the real thing—Messier Marathon. If Wikipedia were to educate me before I accepted your invitation, I might have declined the opportunity to find as many objects as possible during one night from the catalogue compiled by French astronomer Charles Messier. Me? Astronomy? No way! My knees creaked at the idea of staying up from 5.30 p.m. to 5.30 a.m. in the wilderness where the temperature was sure to plummet to sweater-plus-jacket depths. All that suffering just to spot 100 celestial objects? I shut my instincts up and said yes! And, my dear Sarang, I am glad I did. Because your telescope showed me more than those objects. When that one faint star turned out to be a collection of thousands of brilliant stars, I wondered about all the assumptions I make based on what I think I see. When I looked at two galaxies captured within a lens barely bigger than a single eye, I wondered about all that is within me beyond the physical. That coat hanger arrangement could have been shells or pebbles on any beach here. Except that it is a “very entertaining asterism in the Sagitta constellation,” as you put it. Where is that beach? Who is that child? Hazy gases giving birth to new stars; stars on the verge of an explosive death. Dimensions and distances beyond comprehension. Countless. Endless. It was a night that established my own insignificance as man in the grand scheme of things. And made me sad about our infinite capacity to damage the treasures that have been gifted to us. Before we began, a sudden gust of wind threatened to blow away the tent you were trying to erect. Was that a warning? As we wound up, a peacock called from the hills. Was that a plea to wake up to the infinite beauty around us? To be humble before all that we don’t know, yet? Thank you, Sarang. I learnt a lot. But I don’t remember the names of all the stars, nebulae and galaxies you opened my eyes to. I am an old romantic; I would rather let them remain celestial mysteries. You invited me to “explore stars, nebulae and galaxies” and to “explore yourself.” The latter I shall, thanks to that one night with you and the stars. With love, Your fellow earthling Sarang Oak is a passionate astronomer, author and teacher. Photo by Priyanka Kudchikar.

9 Comments

“Effulgence, I like that word.”

I agreed it was a nice word. After all, he was the client. “I like the alliteration: Intimacy of Indore and the aura of Aurangabad.” I was not sure if alliteration would help him sell more rooms in his hotels in the two towns. Aloud, I simply thanked him for liking the line. “You know, I always wanted to be a writer.” Aha! “You are so lucky. You make a living writing.” I could not afford a room in either of his hotels. Not that I admitted it. Maybe I could wangle a complimentary stay? “Effulgence … you are sure you cannot include it somewhere in the heading?” He was pleading for some indulgence. I was positive I could not. “Kerala is a beautiful place. We should have a hotel there. Maybe in a nice town … like Ernakulam.” For a moment, I did not figure out why the conversation had suddenly changed tracks and towns. Then the alliteration hit me. “Did you know about this word flocci something? Wait, I will write it and show you.” He jotted it down on a piece of paper, frequently glancing down at something hidden in the drawer—floccinaucinihilipilification. “We should shock people with our words. I find it fascinating. It will attract them.” Wasn’t he concerned with what the word meant? Obviously not. The meeting was over. Soon, I lost that client, probably because he found me too timid with words. Some months later, his brochure arrived in the mail, inviting me to the opening of their latest hotel in the “effulgence of Ernakulam.” I broke into a sweat when I read that their plan for the next year included another hotel … in Faridabad. First I thought there was an error in the heading: “Why Doctors Need Humanities”. After I read the article I was convinced that “Why Doctors Need to be Humane” would have been a more appropriate heading. Reading the article made me wonder once again: Why do many prominent doctors and hospitals avoid palliative care like, well, the plague. They welcome the best talent and the best technology, but palliative care? “We cannot spare beds for that.” To me, palliative care is synonymous with humane care. A hospital refusing to accommodate a facility for humane care is like a school saying we can give you reading and ‘riting, but no ‘rithmetic. So, why have I have jumped from that Times of India article on Humanities to humane care? Precisely because that article deals with humane care. Learn empathy with the -pathy The problem, says the author, Professor Anand Krishnan, Centre for Community Medicine, All Indian Institute of Medical Sciences, is not that our doctors lack the scientific knowledge. The problem “is related to their insensitive behaviour which emanates from their ignorance as well as inability to handle the emotional distress of sick individuals and their near and dear ones. Doctors should not allow scientific medicine to blunt their humanity, ignore ethics and the need for empathy." Professor Krishnan laments that “A typical consultation today is of less than ten minutes and consists of a few cursory questions followed by a long list of investigations and medicines to be taken with poor explanation of (the) whys and hows.” The death of E Ahamed, a Parliamentarian, kicked up a veritable why-how storm in both political and medical circles. Did they use the right equipment at the right time? Was the family denied access when it mattered most? Instead of resuscitating that controversy, let us take note of what Dr M R Rajagopal, widely acclaimed as the father of palliative care in India, had to say following Ahamed’s death, as reported by The Deccan Chronicle: "Science has to be used on human beings with humanity. Death is the inevitable consequence of life, and there is a time at which a gentle touch of a loved one, a few drops of water down the throat and religious rituals become more important than the latest technology.” Touch to reassure Recently, Dr Priyadarshini Kulkarni, a prominent palliative care physician ended up having to answer the difficult question of a family member, but for an entirely different reason. For long, she had been caring for an elderly woman. With her pain under control, often the patient would request the doctor to just sit with her. Dr Priyadarshini would comply, at times sitting with the patient for more than an hour, simply holding her hand in silence. One day, Dr Priyadarshini was just leaving after what turned out to be her last session with that patient, when the old lady called her back. With difficulty, she sat up on the bed and gave Dr Priyadarshini a warm hug. The patient’s daughter was a bemused witness. Soon, the patient passed away. Days later, during a visit to the house, the daughter asked Dr Priyadarshini: “I was her daughter. I took care of her for so long. Yet, at the end, she chose you, not me, for a goodbye hug. Why?” Perhaps, this is best answered by Dr Abraham Verghese, who received a National Humanities Medal from President Barack Obama in September 2016. During a TED talk, Dr Verghese regretted that “the patient in the bed has almost become an icon for the real patient who’s in the computer…. I call it the iPatient…. The real patient often wonders, where is everyone? When are they going to come by and explain things to me? Who’s in charge? There’s a real disjunction between the patient’s perception and our own perceptions as physicians of the best medical care.” Dr Verghese urges a return to old-fashioned touch, the thorough hands-on physical examination. He calls it a ritual, which he thinks tells the patient: “I will always, always, always be there. I will see you through this. I will never abandon you. I will be with you through the end.” Sharpen left, nurture right Yes, Professor Krishnan, let us introduce Humanities in medical curriculum. Let us revive the book and cinema clubs. Let us encourage our medical students to abandon the stethoscope and pick up the brush or the guitar as part of their course. Hopefully, all this will prevent what Dr Salvatore Mangione of Jefferson University fears: “Medical school attracts those that are left brain, but then proceeds to atrophy what is left of their right brain.” Some medical schools are already into Humanities. Dr Sulabh Kumar Shrestha, a medical oncologist (“loves writing poetry, listening and playing music and travelling”) writes: “I pursued MBBS at KIST Medical College, Nepal and we had ‘medical humanities’ incorporated in earlier years, although we needn’t appear for exam…. We had weekly sessions named ‘Sparshanam’ i.e. touch.” The session titles were “empathy, doctor-patient relationship, the patient, the doctor, breaking bad news (and) compliance.” The students were given paintings, photos, poems and quotes. A 5-minute timer was set for each group to interpret those. “The two major questions that we had to answer were: What do you see? What do you feel?” For most medical colleges, who find it difficult to accommodate Humanities between Anatomy and Physiology, I would like to suggest a few chapters in the medical textbook, which perhaps Dr Henry Gray would have added if he were around. Right after “Leave Your Phone, Touch the Patient” and “Compassion is Not on Prescription” let us introduce a lesson on “Disconnect the Tubes, Just Connect”, followed by “The Family is Patient Only When You Talk” and ending with “Letting Go in Peace is Medical Achievement, Not Failure”. |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed