|

THE UNSEEN FACES SERIES: 2. ROMESH Tomatoes are important. Ask Romesh Kumar, a farmer in Pachote village in Chenani, Udhampur, Jammu. “When we formed groups to try out new techniques to cultivate vegetables and flowers, women farmers from Mandlote village thought it was a joke,” Romesh remembered. They had never been able to cultivate vegetables in Mandlote. So, how were they, some of them helpless widows with children, expected to believe Romesh? Believe they did! In a few months, thanks to the support and encouragement from fellow farmers led by Romesh, they produced enough tomatoes to eat at home. “That was the turning point! From hand-to-mouth survival on maize and the occasional kadam (a local leafy vegetable; Kohlrabi) they now had the luxury of eating fresh tomatoes during family meals!” Romesh said. Of course, Romesh had his own doubts, too. So, he decided to experiment. “I planted 1,300 tomato saplings in about one kanal (eight kanals make one acre). I put to use all the new techniques I had learnt. I ended up getting about 40 quintals of tomatoes!” For a traditional farmer, used to the same manual methods for at least four generations, it was a miracle to end up with that much produce, mound after mound of luscious tomatoes! The traditional farmer in Romesh continued to be sceptical when he went on to plant capsicum. “Nobody has ever grown capsicum in my village on a commercial scale. So, I decided to take a chance with just four lines of plants.” It was a “gigantic” success! The capsicums weighed 250 gm each on an average. Romesh the modern farmer was born; so was Romesh the guide and mentor to fellow farmers. From farmer to leader Born in 1983, as the oldest of three brothers and a sister, Romesh had to give up school during grade 9. “My father was finding it difficult to manage everything. So, I joined him and picked up farming.” He is happy that his brothers were able to complete school. And he will ensure that his two sons (12, 5) get good education. “Maybe if I were more educated, I would have learnt all these new things faster and better.” “Not so long ago, after putting in a lot of hard work across 10 kanals, we would barely get ₹ 1 lakh a year. Now, if you follow the right techniques, you can get the same income from just one or two kanals. It is not a matter of luck, just simple, systematic effort using scientific methods.” The 50 farmers Romesh has guided to prosperity so far are happy to agree. The project that taught and supported farmers like Romesh to cultivate vegetables and flowers was discontinued in October 2018. Romesh goes on. Without all the institutional and expert support, is it worth the extra effort? “Some five years ago, we all started learning together, thanks to the project. Lessons were taught to groups of farmers, demonstrations were given to groups, benefits were given to groups. Individually, none of us could afford to buy a diesel plough. Together we did and that too with government subsidy. We took turns to plough our land. When all of us use our resources like land and water the right way, the benefits are multiplied for every family. Every child eats better and gets the chance to study well. We have to just keep going, try to do better, support one another. I am grateful I was given this opportunity.” His initiatives to help others made him a popular candidate for the local body elections. Not surprisingly, he won the Ward Panch position in December 2018. Being the bridge to benefit Today, he is an important bridge between various government departments and his fellow farmers. He understands the needs of the farmers in different villages. He recommends beneficiaries for government subsidies and schemes including those for seeds and home. How does he pick a beneficiary? “I verify that the beneficiary has a genuine need and the willingness to make full use of the benefit within the prescribed deadline. Else, they would be denying someone else an opportunity.” His days are longer now, and he has to walk longer distances. What else has changed? “I have never felt that I am someone special. I am one of them, another farmer. We have all been through difficult times. Now, a few of us have seen some success. All I am doing is sharing a little knowledge, giving them a little confidence. So that more of us can succeed.” Ashishkumar Patel, a development professional, who worked with Romesh through the duration of project, said: “Projects may start and end. But it takes a hardworking local person to assume the leadership role to ensure its success during and, more importantly, after the project is over. I am happy to have witnessed Romesh’s growth. Now, his personal mission is to continue to work for everyone’s success. I am sure Romesh will achieve greater success in this project.” As usual, Romesh’s day had started before the sun rose. Now, before it gets too hot, he is gearing up for a regular trek, with his brothers who are his co-farmers and a couple of neighbours. They load some crates and gunny bags full of capsicums and tomatoes on two mules. The rest they carry on their heads and shoulders. They have a testing kilometre and half to cover, all uphill. Once they reach the highway, the produce will travel to the market. And Romesh will proceed to a meeting with the government officers and community members. THE UNSEEN FACES SERIES: 1: GUS

8 Comments

After I read a newspaper report about the state of drought in Maharashtra and how man and animal were both at the mercy of the next monsoon, I called up my friend. He is the CEO of a company that is involved in corporate social responsibility (CSR) work (including water conservation) in several villages. “I appreciate your concern, Mohan! We now have someone looking after our CSR activity. I will ask him to speak to you. Catch up later!” That was abrupt! Was he too busy running the business to bother about CSR? My conversation with his new CSR Manager a day later was revealing. “Thank you, Mr Joshi for your interest in my work. To be honest, I am busy with my year-end paperwork. I have budgets to prepare and I need to close year-end issues with our partner NGOs. Your suggestions are great, but I just don’t have the bandwidth to take up anything new. I have just one intern to help me. And the boss wants the impact presentation tomorrow.” While I commiserated with him, I could not help wondering if the profit centres in my friend’s company made do with one intern and used that excuse: no bandwidth. Saving 5000 mothers Around the time Indian law mandated companies to spend a portion of their profits for social good, some of us were in Jawhar, a remote district in Palghar, Maharashtra. This place had various problems, but the specific issue on our radar was maternal mortality. It was a familiar story—early marriage, the pressure to give birth to a male child leading to repeated pregnancies, no access to medical care and utter neglect of nutrition. Haemoglobin levels in expectant mothers in the region were at times less than 4 g/dl (whereas in a normal, urban setting a drop below 10 g/dl is enough to set off alarm bells). Over the next three years, we achieved a fair amount of success—Hb levels rose, maternal mortality fell. Apart from the government, the Indian Medical Association and the NGO Pragati Pratishtan, many shared our work and the satisfaction we derived from it. Meaningful engagement I remember interacting with the audit team from one of the companies. They came there to ensure the medicines were being put to good use. They went back transformed, having seen how they were helping transform the very lives of poor villagers and save many mothers and infants. I shared the Jawhar story with my busy CEO friend as we met at a Rotary lunch. I believed the audit team went back more committed to their employer, more charged up to do better work, I told him. And all of them became ambassadors for their company’s products. The other participating companies too must have experienced the positive change, if they had bothered to keep their customers and employees posted. I was getting somewhere, but I could see my friend was still sceptical. “So, like you guys did in Jawhar, my employees go out there, solve the drought and my business booms, is that it?” he smirked. Precisely! I ignored the sarcasm. “Listen, the law wants me to spend 2% on CSR and I am doing it. Beyond that, what’s in it for me?” When you do good, sustainable work, you are fulfilling your responsibility to society. And, in the process, when you ensure your brand gets greater visibility, you are fulfilling your responsibility to all those who have a stake in your business. That's what's in it for you Having been his mentor, I knew some of the problems his company was facing. Their product was technically superior. However, it was also pricier and struggling to survive in a market flooded with hundreds of cheaper, me-too competitors, who were more aggressive advertisers. His company comprised several islands of excellence. The silos were deeply entrenched. Much as my friend tried to build them, the “we-are-one” bridges never survived for long. At the same time, they were doing some good work on the CSR front. They had fabricated a library on wheels, the only source of books for schools in several villages. And their little water tankers on three wheels were the only source of drinking water in remote locations as the severe drought singed crops and lives. Imagine, I told him, that you were some 20 years younger. You are social-media savvy, discerning and passionate. You are bold, intelligent, a fantastic team player and, yet, ever willing to trek down a new path. He must have liked the picture I painted because he was smiling. Now, would you like this younger version of you to be your customer? “Yes!” Would you like to recruit him? “Of course!” Perception as a differentiator Suppose you had taken pains to make this young you aware of the good work you are doing in the villages around the factory. Is he likely to pay more for your product that is helping children read? Will he feel proud to belong to a company that is reaching drinking water to families living in barren lands? Even if he were not aware of your niche products, would he easily recollect your brand because the name was emblazoned on vehicles engaged in keeping the length and breadth of the town clean? When you do good, sustainable work, you are fulfilling your responsibility to society. And, in the process, when you ensure your brand gets greater visibility, you are fulfilling your responsibility to all those who have a stake in your business. We talked for long. At the end of it, he wanted me to go over and address his senior team. I hope your CSR Manager would be present, too? “Of course!” I agreed to meet them after two weeks. I needed that time to put together some resumes to beef up his CSR department. That band deserved more width. This was first posted by Mr Mohan Joshi in two parts in LeaderConnects. Abridged and re-posted with permission.

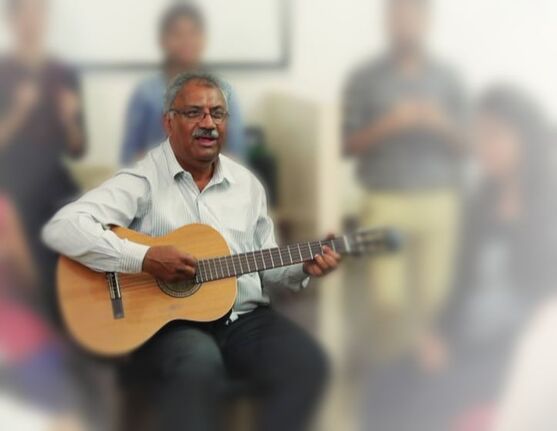

"I want to be someone capable of seeing the unseen faces, of seeing those who do not seek fame or glory, who silently fulfil the role life has given them. I want to be able to do this because the most important things, those that shape our existence, are precisely the ones that never show their face." Paul Coelho Like the flowing river Meet Gus in the first of a series featuring "unseen faces".  1963. Gus, 12, has just won the full house in Housie (Bingo) in his school. The prizes had been on display even before the game started. He is eager to receive the first prize from the school’s Summer Holiday Camp Manager. It is a beautiful statue of Our Lady. He can’t stop smiling when he accepts it. Then, in a moment, his world changed. “You take this,” the Camp Manager took away the statue and handed him a smaller bust, which was chipped. The boy who had won the second prize happened to be from an affluent family and deserved the better prize, a shocked Gus was told. Surely, it would make no difference to Gus, right? Gus felt angry and sad. An inferior prize, just because he was poor? He was already waging another battle at home. Because he was standing up to an alcoholic and trying to protect his mother and four little siblings. He felt responsible for them. Why was the world so unfair, Gus wondered. He just had to grow up and find a job, any job, that would give him money so that he could look after his family. 2019. Gus is overseeing another game of Housie with a group of girls and boys, all around the age of 16. For every boy and girl, it is an effort and an achievement to face a group of people and read out the numbers by turn. Gus gently prods a boy to make eye contact while announcing a number. One girl who has problems with her sight and hearing (“I want to be an accountant”) is helped by her neighbour. There are no statues; the winners get mints and chocolates. The real prize is the time they get to spend together, to work together and to enjoy themselves. They are all equal. At every opportunity, Gus slips in a tip, a piece of advice. Through games, dance and music they are picking up social skills. And, for them, something that is less difficult to spell than to acquire —confidence. When Gus steps out of the room, I play the devil. “Gus sir is saying do this and don’t do that. Do you think he is being practical? The outside world is so different. And surely money is important.” “No! Gus sir is right. He is telling us the right things.” That’s the girl who would be an accountant one day. “I had so much fear. Now I think I can do something.” “He listens to us,” avers another. He is now less conscious of his appearance. And a lot less angry with the world than when he had joined. “Yes, money is important,” a boy patiently explains to me. “But it is no more important than petrol. Sure, you need it to go from here to there. That is not the whole journey, though.” Some of them have learnt to play the guitar “somewhat”, thanks to Gus, they tell me. They were scheduled to have a dance session, but a neighbour was not happy with the noise of the ghunghroos. So, they have to figure out a new location for dance sessions. And all of them have been with Gus sir for barely a month. Au(Gus)tine Mendonca is, by qualification, an engineer. However, he considers himself a “people person”. “I was working in Bahrain for nearly 15 years. Initially, the local boss would keep calling me ‘Hey Indian’. It was infuriating. Then I realized they probably found both “Augustine” and “Mendonca” a mouthful. Next time he called me ‘Indian’, I told him he could call me Gus. And the name stuck.” Gus says he has “corrected” his career. “I took up engineering because I was desperate to qualify and start earning. If I could go back in time, I would probably take up HR. Not the admin-kind of HR, but the people-kind. Understand them, work with them, motivate them. That kind of HR.” The Bahrain stint helped Gus clear all the family debts. When he returned to India, he worked with various companies including an engineering company and a hospital. The engineering company once faced a drastic fall in output during the night shift. Gus spent time with the workers and figured out the reason. As a cost-cutting measure, a supervisor had withdrawn the mosquito repellent they used to give all employees. Now, instead of manning the machines, they were busy slapping the mosquitoes. Gus got the repellent back and, sure enough, productivity was back on track. The famous but abrasive chief of the hospital was angry. Everyone feared his morning rounds. “Why do you have your rounds immediately after mine?” he once asked Gus. “So that I can undo the damage you do,” Gus replied. Gus had a collection of doctor jokes, which he used liberally during his rounds. Those served to soothe frayed nerves and restore morale. “What nonsense!” the chief roared. “Tell me one of those jokes right now.” Gus did. And the chief burst into laughter.  Apart from doing the jobs that came his way after the Bahrain-stint, Gus also felt a pull to seek out the less privileged and help them. He worked at a night school and assisted a couple of NGOs. Once at the night school, he saw a boy sitting outside on the steps. Gus asked him why he was not in class. The boy had been thrown out because he had beaten up another boy. His language was harsh, almost abusive. Gus sat next to him. “There is so much age difference between us. Do you think we can have a more polite conversation?” The boy looked at him. “You are the first person who wants to talk to me.” And the story came out. The boy had lost vision in one eye in a playground accident. Ever since, he was called “blind” by other children. He was constantly ridiculed and forever the butt of cruel jokes. The teachers also wrote him off and joined the students in abusing him. That day, he opened his notebook to find that someone had written an abuse targeted at his mother. The violence followed and the teacher was prompt in expelling the boy from class. Gus summoned a meeting of the teachers and asked for an explanation. “That boy is impossible; he must be removed from the school.” Gus interrupted the chorus. “That boy will not be removed,” he was categorical. Then he proceeded to find out exactly what the teachers knew about the boy. Had they bothered to find out anything at all? A few days later, Gus ran into the boy again. He was all smiles. “I am back in class. They are talking to me now. They are nice.” “Sometimes, all they need is a hand, a chance. Just what I needed once upon a time," Gus said. “It is so easy to brand someone as bad or impossible. Just dig a little deeper. I did once. And behind the alcoholic I found a jovial, talented and loving man. If you must, hate the problem, not the victim. “When the boys and girls come and tell me they are eager to get any job so that they can start earning, I understand. But I don’t want them to make the same mistake that I did. So, I talk to them individually, find out what they are interested in and try to guide them accordingly. “A few companies are very happy to employ these boys and girls. They say they like the attitude and the willingness to work hard. That is so nice of them. “Some of those I had the opportunity to help are doing so well now. They stay in touch. They come and meet me at times. “Of course, in some cases, I failed. They started earning and money derailed their lives. Bad company, expensive addictions, and the wrong notion that they had ‘arrived’. “In every case, I begin with a positive intention, whatever the outcome. Unless I am confident of them, how can they be confident of themselves?” Says Yogesh Kapse, a social development professional, who has been working closely with Gus, “It becomes easier for us to support a project when we know that there is someone as passionate and as committed as Gus mentoring it." Apart from imparting “employable skills” to the youth, Gus shares art and poetry with all. Today is song time. He picks up the guitar and the boys and girls join him in singing their “special” song: I am special You are special We are special, you see Black or white Short or tall Fat or thin All of us are special, you see. Augustine Mendonca is currently associated with Parineeti Projects.

|

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed