|

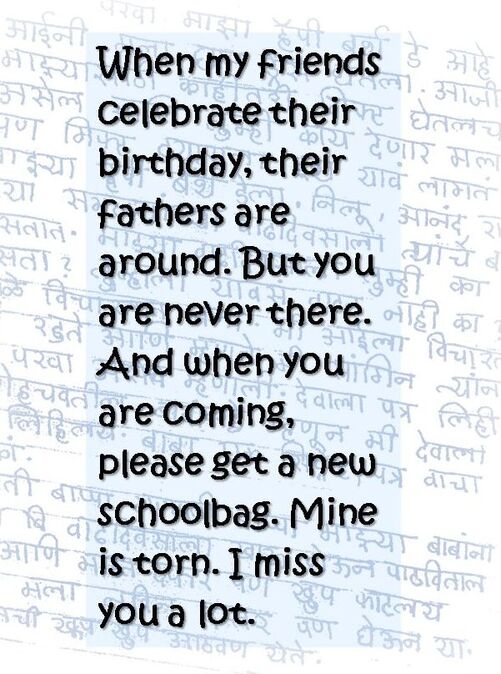

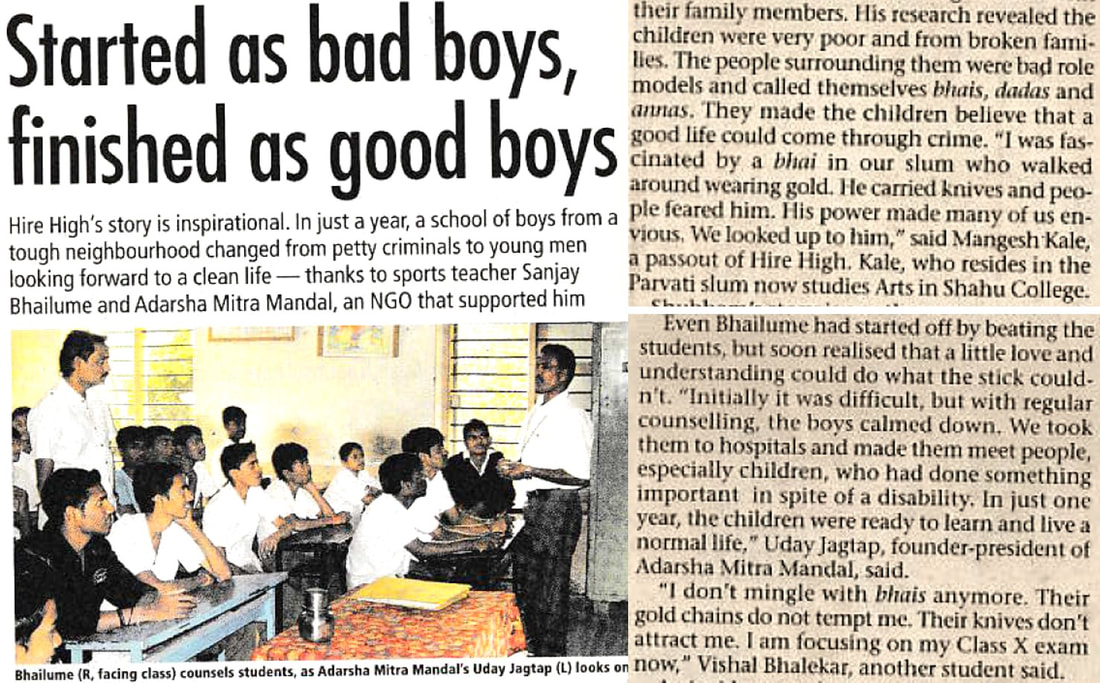

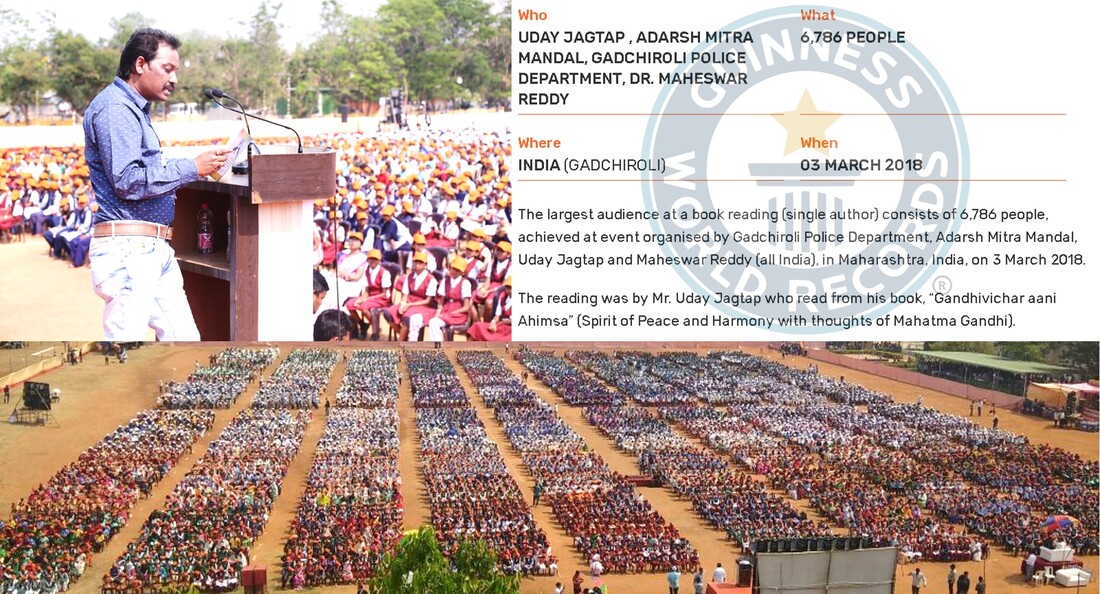

THE UNSEEN FACES SERIES: 5. UDAY Uday was about 11 years old when he saw his elder sister being teased on her way to school. That prompted Uday to start learning karate. He went on to become a popular martial arts instructor in Maharashtra and very successful in national-level tournaments. Years later, Uday was at a court in Pune to meet someone when a boy called out to him. “Sir, what are you doing here?” Uday recognized him as one of his karate students. That boy was with several others, who were all carrying their schoolbags. They had apparently decided to skip school to come to the court. Why? They wanted to see a notorious criminal who was to be produced in court. “He was their hero. I thought it was urgent and important to give them another role model,” Uday remembered. “Else, they were sure to follow their hero and take to crime.” That incident started Uday Jagtap’s journey to turn people, especially children, away from crime and integrate them into the mainstream. So far, that mission has fetched Uday many honours, including a Guinness world record. Giving crime an option Uday believes that for most people, crime is not the primary livelihood option. “The first crime is often the result of an impulsive action or an accident. That lands them in jail, and they get branded as criminals. When they are released, no one is willing to give them a job, nor do they have the money to start some business. Whether they are reformed or not, they are left with one option to survive: crime. And the child of a criminal is more likely to turn to crime,” Uday said. With the help of his family and some friends, Uday produced a small film. It showed a young man, like many in Pune, who felt proud to commit a crime. The film focused on the plight of the family after he was put away. How the young wife struggled to eke out a living. The gradual change in the attitude of his friends, who were once his admirers. Far from making him a hero, the film depicted how crime made him a victim and caused untold misery to his family. Uday used this film as an ice breaker when he set out to understand the mindset of a criminal. He got permission from the authorities and visited Yerwada jail. “I showed them the film and had long discussions with about 2,500 inmates. The hardened ones apart, many of them regretted their actions, but had no clue how to get on with their lives once they were released.” Just to drive the message home and to ensure they were committed to turning over a new leaf, Uday drafted a letter. It was from a daughter who was missing her father at every birthday. “Day after is my happy birthday. When my friends celebrate their birthday, their fathers are around. But you are never there. Don’t you feel like coming? Everyone asks me. When I ask mother she just cries and promises to tell you.” The letter ends with a plea to Ganpati Bappa to send her father to her with treats on her birthday. “And when you are coming, please get a new schoolbag. Mine is torn. I miss you a lot.” Of the 2,500 prisoners who received that letter, 190 sent a reply to the jailor saying they wanted to start a new life. “In response, an NGO that I belonged to, Adarsh Mitra Mandal, promised to support the education of their children. Also, the jailor chose 26 of them who were due for release and recommended them for suitable jobs. We found them jobs based on their qualification, experience and interest. Eleven years later, some of them have found new jobs or have started a business. But, not one of the people we supported went back to crime,” Uday proudly stated. Correcting them young Uday thinks it is important for every child to have a healthy role model. Everyone appreciates an example like Sachin Tendulkar. However, “when you are growing up in a crowded slum or chawl, where most fathers spend time drinking and mothers are too busy keeping the family going, even Sachin can fail to score,” Uday pointed out. “It is easier to look up to the local goon who appears to lead a lavish, fearless life. We countered this by putting up photos and messages of well-known saints and historical figures at many homes. This had an immediate impact on the alcohol problem. Maybe the fathers found it a little awkward to drink when a Sant Gnyaneshwar or a Mother Teresa was keeping an eye on them. The ultimate beneficiaries were the children,” Uday said. There was one school in the locality, which was notorious for a high failure rate and rowdy behaviour. The pinnacle of achievement for many children was to feature on hoardings that celebrated criminal elements. “We worked with the teachers and the local police to identify some of these children. Soon, we were counselling some 24 children. We held classes for them in police stations. On the one hand, the children got to see where criminals ended up and the fate that awaited them. On the other hand, the initiative empowered policemen, used to being punitive, to become proactive in helping build a healthier society. We named this police-public project Parivartan." Sports libraries were another initiative started by Uday. “We keep complaining that children are addicted to the mobile and TV. But, as parents, we don’t or can’t afford to do anything about it. A sports library makes it easy to keep children occupied in healthy games. Any child can borrow a play equipment (bat, ball, chess set, skating shoes, etc.) for up to three days for a daily fee of one rupee. We urge them to play without fear; they will not be penalised if some equipment is damaged during play. For cricket bats, we put in a condition. They must find at least another 10 children to play with. As a result, we witnessed the formation of some informal teams. The heartening part is that even after eight years, the teams are still playing together. We have 3 sports libraries functioning in Pune and 25 in Gadchiroli.” The call of Gadchiroli Gadchiroli, situated about 900 km from Pune, is notorious for Naxal activity. Over four years ago, Uday happened to catch a news headline on TV: some Naxalites had been arrested in Pune. He wondered: if the violence that has caused so many deaths over the years can come to Pune, why can’t peace go from Pune to Gadchiroli? “My first reaction was to get in touch with the top police officers in Gadchiroli and tell them that I wanted to do some social development work there. Initially, they discouraged me saying that the ground situation was very bad, and I was better off doing my work in Pune. But so many policemen, so many adivasis dying! For what? I just couldn’t sit back, watch the news and be safe in Pune. I went to Gadchiroli.” Based on his Pune experience, Uday started helping the children first. “The children were innocent victims. They had to walk for 5 km or more to reach school only to find that there were no teachers. Most of them lived in thickly forested areas. We first got the children some bicycles. With generous help from Rotary and my friends, we managed to give them 110 bicycles.” Then came electricity. “I was warned that there would be severe opposition to electrification from the Naxalites. For me it was symbolic. More than 70 years had passed since the nation gained independence and they were still in the dark. They deserved light. We began with five schools and then lit up more than 1,000 homes with the help of solar power. Some of the old people at home would just sit and stare at the lamp at night. It was something they had never seen, never even dreamt of.” It was not possible to force the teachers to risk their lives and come to school, but it was possible to reach education to the children. “We set up e-learning facility in three schools. Attendance improved, not just of students but also of the teachers, who now faced a different problem. With students going to schools that had e-learning, the other schools were in danger of being derecognised for want of students. I met a group of 40 teachers, and they pushed the government for e-learning in more schools. At the request of the government, and with the help of Rotary, we set up e-learning in 1200 schools. Now, the teachers maintain the system and ensure regular update of the software.” While e-learning was a giant leap, it did not cover all children, especially those in remote areas, too difficult and too dangerous to access. Uday and his team worked out a solution--Gyanganga! “We set up libraries in all police stations. Most police stations in Gadchiroli are like fortresses. Once a policeman enters a station for duty he may not come out for over a month. But the children could go in and come out easily and safely. It worked well for the police and the children!” For those children who could not make it even to the stations, the police ensured that the library reached them. “We set up what we called ‘cot’ libraries. We would take the books to a village and spread the books on a cot. The children would come and read. The library would remain in one village for two days.” Uday wanted to help the children lead as normal a life as possible, away from the threat of guns and the shadow of death. So, following the Pune model, he also set up sports libraries in various police stations. Public health facilities were almost non-existent. The solution: mini ambulances, equipped with all essential facilities, manned by a medical team and operating within a 10-km “safe” radius. “It was a problem keeping the motorcycles refuelled at all times, ready for action. So, working with an engineering company in Pune, we have recently developed an e-ambulance than runs on three wheels for 80 km on a single charge. We will be deploying these soon.” Changing perceptions It was a happy sign that many Naxals were giving up violence, surrendering their weapons and accepting government support (land, means of livelihood) to once again live peacefully. However, Uday thought more needed to be done. “They had taken to the violent way of life after they were brainwashed. Now, they were willing to return to the mainstream but was it not necessary to reboot their mindset? We resorted to Gandhigiri to achieve this end. We offered those who had surrendered an opportunity to become familiar with peace and non-violence through Gandhiji’s teachings. We gave them books. The police and I would talk to them. Finally, 56 appeared for the Gandhi Vichar examination.” Uday added: “It was a very significant moment for all of us. Those who could only think of violence were now wearing white caps of peace. Hands that held murderous AK47 guns were now holding simple pens with the power to transform lives.” Also, “there were attempts being made to fan inter-caste conflicts. With tremendous support from the police, we got leaders of different religions to talk to the people (especially children) and answer questions. It was soon clear to everyone that no religion advocated hatred or discrimination.”  Winning the battle against violence. Left: The winners in the Gandhi Vichar examination conducted for reformed Naxalites. Right: Children who did well in the Sadbhavana examination. Arrayed behind them are leaders of various religions, who taught the children that every religion advocated peace and harmony with all. G for Gadchiroli, the Guinness record holder While this transformation was revolutionary, Uday was convinced that making an impact would require the involvement of children. They were the ones who could bring about a radical change in the way the world looked at Gadchiroli. It was time for good thoughts to find expression as good words and set up one good deed that the world would applaud. It was time for Gadchiroli to bask in the Guinness limelight. The team mobilised 13,500 children from 273 schools for a Sadbhavana examination. The children were exposed to thoughts of leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, other historical figures and the religious leaders they had interacted with. The participants also had the opportunity to express their own thoughts on peace. Based on all these inputs, Uday Jagtap penned a book Gandhivichar Aani Ahimsa (the thoughts of Gandhi and non-violence). This was read out by nearly 7,000 residents of Gadchiroli (mainly students) creating a new Guinness World Record: “The largest audience at a book reading (single author) consists of 6,786 people, achieved at an event organised by Gadchiroli Police Department, Adarsh Mitra Mandal, Uday Jagtap and Maheswar Reddy (all India), in Maharashtra, India, on 3 March 2018.” Uday said, “I told the children that it was up to them to change the way the world saw Gadchiroli.” This world record is what Gadchiroli should be remembered for, not violence and not backwardness. You have made it happen, you can make it last.” A copy of the world record citation was given to all and now occupies a pride of place at more than 7,000 homes. “According to a police survey, the Naxal movement has seen no fresh recruitment in the last four years or so. I am confident a new Gadchiroli will emerge in another five years,” Uday is positive. He conducts regular educational tours to Pune for the children of Gadchiroli. “It is hard to believe, some of them have not seen a world outside the forest where they live. The visits and the interactions open their eyes to possibilities beyond a life of fear, suppression and violence.” We are at peace only if all of us are “I may provide all the comforts to my children. But in the process if I totally ignore my neighbour who continues to live in misery, anger and frustration, I am putting my family in danger. We are safe if all of us feel safe. We are at peace if all of us are at peace. So, the motive behind social work is in a way selfish. That’s how I see it,” Uday smiled. He is grateful for all the support he has received. “There is nothing that I could have done alone. I have had great support from the police in Pune and in Gadchiroli. My friends in Adarsh Mitra Mandal have been with me every inch of the way. There are many organisations that came forward to help financially and otherwise. Many are keen to take up new projects.” Doesn’t he fear for his life when he works in the jungles where every shadow hides possible death? “Of course, there is always a threat and I keep getting indirect messages to stop what I am doing. Fear does not help. At the same time, when you become a martyr, you end up being just another statistic. To do more and to help the cause of progress, you need to remain alive. Therefore, while working, I do take basic precautions.” Yes, there have been failures. There have also been touching moments, “more precious than any record.” “There was this old woman who would keep calling me at every odd hour. She was living alone and was unable to move around. Her daughter lived at a distant place with her husband, who was a violent alcoholic. The mother was worried the son-in-law would one day kill her daughter. I would keep reassuring her that within 10 minutes of her call either the police or some friends would reach her to help. One day she told me: ‘Beta, when I speak to you, I am able to sleep in peace. That’s why I keep calling you.’” Then there was another old woman who rebuked him. “Several years ago, at the time of Ganesh festival, we screened a movie that showed how boys could put on fake looks and make false promises to lure gullible young girls. An evening after the show, one elderly woman got up and roughly caught hold of my shirt. ‘Why didn’t you make this two years ago? You would have saved my daughter.’ Then she broke down.” At 47, Uday heads a business that employs 350 people across 8 offices and deals with 94 well-established companies that outsource work to his enterprise. “Most of the money for the social work I do comes from here. Also, the people who work with me typically contribute a month’s salary. Then there are project-based donors.” As his family pleads with him to be careful for their sake, he is now focused on delegating old and new projects to other NGOs and individuals, who are genuinely interested in social work. And he continues to make regular visits to Gadchiroli. What next? “Pune is supposed to be a pensioner’s paradise, the Oxford of the East. Instead, we now have increasing unrest, violence and worsening traffic. I have started some work on tackling the traffic problem. Plus, I would like to do more for children. Recently I managed to expose the menace of hookah-pens and e-cigarettes. The government has now banned its use. There is so much to do.” Uday Jagtap is far from done.

12 Comments

|

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed