|

Mention law and most of us immediately visualise a court-centric complex system populated by lawyers and judges who tackle the incomprehensible rules and provisions populating thousands and thousands of intimidating pages. Now think of a situation where you are helpless, bed-bound and your life (or its peaceful closing) hinges on someone pulling off a legal miracle. Just when you have given up all hope, an advocate reaches out to you and resolves the situation you are facing with a large dose of selfless compassion. What would you call her? A saviour? An angel? A miracle? Well, she prefers to be called Sandhya. Advocate J. Sandhya is a practising lawyer based in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. She is also a social activist, and a former member of the Kerala State Commission for Protection of Child Rights. For the many she has helped and continues to help, she is the humane face of law. Many. Like Maya. And Asha. The rebirth of MayaIt was during the Covid years that a neighbour with the help of a social worker found Maya all alone at her rented home. She was smitten by some disease that had paralysed her. The home was flooded and infested. It was not easy to move her out. When she was admitted to a palliative care facility, Maya was not in a condition to move, talk, or remember anything. After several days of care, including physiotherapy, Maya dodged what had appeared to be lurking round the corner: death. When Advocate Sandhya stepped in, Maya had started to make efforts to talk. The first thing that Sandhya did was go to Maya’s home and shift all her stuff out. The landlord had insisted on this. Which posed a major question. Where would Maya live now? Based on the information Maya gave her, Sandhya contacted Maya’s uncle. He came and but did not wait for too long. He declared (in legalese) that he had nothing to do with Maya and he was not to be called again. It was heartbreaking for all to see Maya’s plight, but Sandhya was not ready to give up. Her conversations with Maya had revealed that Maya’s parent used to work in a prominent central government office. Sandhya contacted the organisation and informed them about Maya. Yes, as the only surviving member of the immediate family, Maya was entitled to a pension, provided there was documentary evidence linking her to the late employee of the organisation. Sandhya had to start from scratch. Painstakingly, she gathered enough evidence to establish Maya’s identity and her connection with the parent. It required a lot of paperwork and plenty of trips to the organisation’s office, all funded by Sandhya. Then, taking pity on their ex-colleague’s daughter, a few compassionate people in the organisation started coming to Sandhya and Maya to help them with the formalities. Finally, the official announcement came: Maya was entitled to a monthly pension of ₹30,000. On the health front, Maya was making very slow progress. But now she was very excited. The pension was giving her a second life. Perhaps she could afford the rent for another house and start all over again. Sandhya said, “For most of us, palliative care signifies that the end of life is very near. Not necessary! Sometimes, we witness miracles. And, with hope and care, some patients like Maya bounce back.” Given Maya’s condition, no one had imagined that she could get a regular income. “My thinking was about getting Maya back on her feet,” Sandhya explained. “From whatever I could gather from Maya, I surmised this pension was a strong possibility. As a lawyer, all I had to do was make a good case for it in terms of documentation. Fortunately, it worked out.” When a scam hit AshaAsha was ill, very ill. All she had as family was her son. Instead of going to school, the son would just hug and sleep with her at the government hospital where she had been admitted. What if she died when he was away? By the time Sandhya stepped in, the mother and son had been in the hospital for more than 40 days. Even if they discharged her, the doctors did not know where they could send her. The advocate managed to crowdsource some funds and get a private sponsor so that Asha could move to a rented house and the son could carry on with his education. Asha and her son moved to a small home. While Asha continued to face challenges with her mobility, life appeared to be slowly getting on track for both of them. But they remained desperate for money. One night, around 1 a.m. Sandhya got a frantic call from Asha. The latter had just received a call from the police cyber cell. They were coming to arrest her for being instrumental in moving one crore rupees of scam money through her bank accounts. Some weeks previously, Asha had received a call from an unknown number offering her commission if she opened new bank accounts and shared the details with them. Given their dire need for income, this was too irresistible a proposal for Asha and her son. Caution stood no chance before desperation. So, the son helped mother visit four different banks on her wheelchair. Of course, neither of them had any idea they were being played. Advocate Sandhya contacted the cyber cell and shared all the information with them, complete with photographs and documents. She made it clear that Asha was not a villain but a helpless victim in poor health. When they insisted on arresting and moving her to the north of India where the scam had originated, Sandhya agreed. However, she warned them that she was unlikely to survive the journey. Today, Asha is about 45. The son is 18 and has completed his ITI course. Her physical and financial struggles have not ended. But Asha is immensely grateful that she has the backing of someone like Sandhya. A little law, much loveSays Dr M R Rajagopal, Chairman Emeritus of Pallium India: “We are grateful to Sandhya for providing voluntary service whenever we seek her support on behalf of poor patients. There is always a sense of urgency when we reach out to her and she would gladly and efficiently help us, mostly by avoiding tedious litigation and by practical mediation.” He cited two instances. A young woman was dying of cancer. Her only daughter, eight years old, was clearly at risk of being harmed by her father from whom she and her mother had been separated for six years. Sandhya approached the Child Welfare Committee of the district. In two days, she managed to obtain an order that granted custody of the girl to the grandmother in the event of the mother’s death. The mother died after five days, in peace. A middle-aged woman, who had been abandoned by her family, was dying of cancer. Her only support was a home nurse, who was looking after her ever since she was diagnosed with the illness. There was every possibility that some member of the estranged family would return to claim the property after she passed away. So, she wanted to prepare a will, leaving her property to the home nurse. Sandhya helped her prepare and sign the document within the limited time that she had left in this world. She too could now leave in peace. Disputes are all too common when life is setting. Not just about division of estate but also about how long one should be kept alive on life support. How long should one extend the suffering of not just the patient but also the members of the family? As a person hovers between life and death, the challenges integral to both get magnified. Often the situation is beyond medicine (and palliative care) and a little practical nudge from someone well versed with the law and its application brings immense relief to all. Sandhya believes that law need not be impersonal and intimidating. “Institutions like Pallium India are doing a wonderful job taking care of health and life. Very often, law can make a significant contribution at the right time. Yes, the knowledge of law is important. More important is the willingness to help and to use one’s skill for the sake of humanity. Anyone can help in one way or another. I just happen to specialise in law and its practical aspects.” May Sandhya inspire more of us to help, one way or another. Names and some identifying details of all beneficiaries of Sandhya’s support have been changed to protect their identity. Image used solely as an illustration.

0 Comments

How would you like a lawyer by your side when you are critically ill? No, not to finetune the will. But to compassionately mediate as you, your family and the doctors struggle to take critical decisions about your very life. Nancy Dubler, the lawyer-turned-bioethicist who “pioneered bedside methods for helping patients, their families and doctors deal with anguishing life-and-death decisions” would have loved to help you. In its tribute to her after she passed away on April 14, The New York Times described her as the “mediator for life’s final moments”. She was 82. Dubler founded the Bioethics Consultation Service at the Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, USA. The Harvard-educated lawyer did this to “level the playing field and amplify nonmedical voices in knotty medical situations.” The team included lawyers, bioethicists and philosophers who carried pagers to alert them about ethical emergencies. In her 1992 book, Ethics on Call: A Medical Ethicist Shows How to Take Charge of Life-and-Death Choices, Dubler observed that modern medical technology “lets us take a body with a massive brain hemorrhage, hook it up to a machine, and keep it nominally ‘alive,’ functioning organs on a bed, without hope of recovery.” And the bioethicists help to untangle the “web of rights and responsibilities that ensnares all patients and caregivers.” Clarity cuts through silence, liesIt was at the end of 2005 that’s Dubler warned about the exponentially increasing conflict in medicine. Nineteen years later, the confusion and the conflicts have only got worse. Economic factors like insurance now play a significant role. As Dubler put it, “The dynamics of the doctor-patient and provider-patient relationships have been deformed by the increasing focus, in fact and in the media, on the cost-containment thrust of both managed care and acute care medicine. There are simply more parties to any decision and thus greater potential for misunderstanding, misinformation, disagreement, and dispute.” In A Hastings Center Special Report on Improving End of Life Care Dubler cites a case when the ICU team requested bioethics mediation because the family was not letting them discuss with the patient about his future care. The patient was alert and aware and had recently been removed from a ventilator. The decision they needed was about placing him back on ventilator in case the need arose. The medical team told Dubler that the patient’s multiple cardiac problems had been “addressed to the maximum medically.” His two sons, loving, devoted and who stayed with the patient, vehemently opposed any such discussion as they felt it would upset their father. The sons knew that their father was very sick but “the independent and proud person” needed hope to go on. Dubler cited studies that established “when family members try to shield the patient from bad news, the patient usually knows the worst, and the silence is often translated into feelings of abandonment.” Finally, they thrashed out a format and Dubler spoke to the patient. After reintroducing herself to the patient who was “clearly very weak and tired,” Dubler asked if he would want his sons to make decisions for him if he was unable to do so. He was also okay with the order of decision-making, the older son first. Then came the important question of whether the patient would be willing to be intubated again if the doctors thought it necessary. The patient said, “I would think about it.” This mediation defused the conflict about sharing information with the patient. At least, the patient and everyone else had a resolution with which they could work. As Dubler observed, “The mediation prevented the bifurcation of family and staff. It was labor intensive, requiring two hours, but it provided clarity going forward.” The tools of bioethics mediationThe bioethics mediator comes “fresh to the facts of the case, impartial to the situation of the case, uninvolved in the prior treatment decisions in the case, and unallied with any party in the particular disagreement.” The process helps the parties to identify their goals and priorities and to generate, explore, and exchange information and options. Of course, the agreement reached must have sufficient and realistic structural supports to become “the reality of care.” As Dubler stated, bioethics mediation helps to:

Conflict in end-of-life decisions can be potentially destructive for surviving family members. Skilled bioethics mediators committed to managing, not banishing, disputes can help to tame some conflicts. In her tribute to Dubler, Nancy Berlinger, a senior research scholar at The Hastings Center, says: “She always kept her eye on the reality of the experiences of being a patient, being a family caregiver, being the clinician in the room, and being responsible for the care of this patient and for discussions with this family. She would remind clinicians of their basic ethical duty—to be faithful to that person in the bed—and would remind bioethicists that when we were discussing ethical challenges, identifying principles, and crafting guidance, the same duty applied to us.” Thank you, Nancy Dubler, for devoting your life to helping many lives depart in peace, without being shrouded in conflict. Reading about Dubler introduced me to the concept of bioethics mediation and raised some questions. Is this practiced in India? Is it part of palliative care? If it is not, should it be? If feasible, should a compassionate lawyer be a part of the team responsible for the patient in the final stages? I am hoping to be educated by my knowledgeable friends in palliative care. Sources

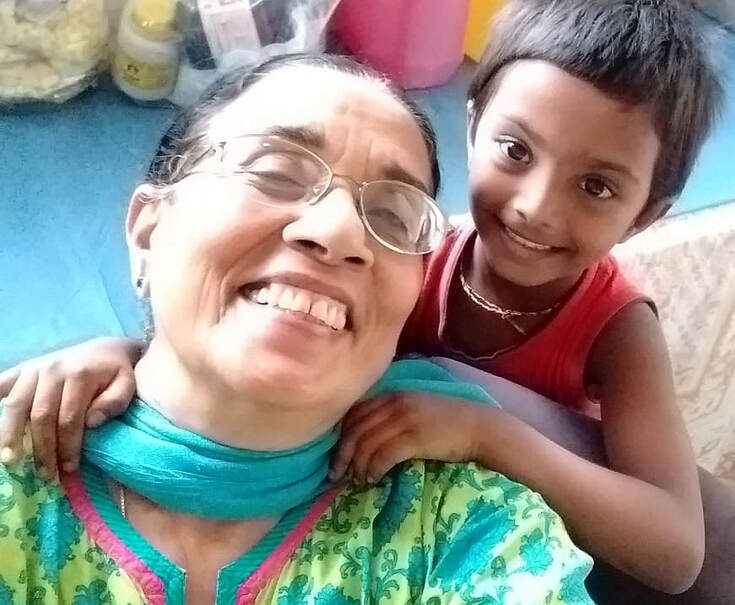

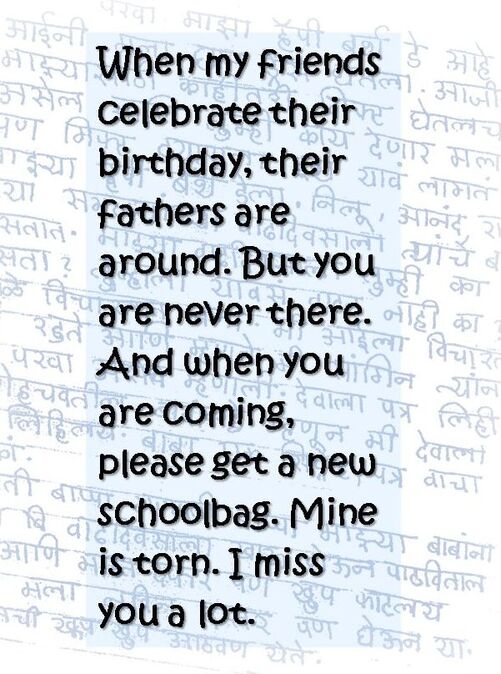

Improving End of Life Care: A Hastings Center Special Report, November - December 2005. The New York Times, May 10, 2024. Image of Nancy Dubler: The Hastings Center. Last Sunday, the day the world celebrated mothers, was no different for this mother. Her two sons, 33 and 31, are growing without hunger, pain, joy or sorrow, thanks to her. But do they even know her? Sometimes they do in the dining hall what they ought to do in the bathroom. Or do in the kitchen what they ought to do out in the yard. Radhamani would discover after cleaning up the mess that the younger was down after another epileptic fit. She would rush to find someone to mind the elder son and then rush to the hospital to fix the wound. She has just one persistent sorrow. That they don’t know her, her love. Every moment, she pines to hear them calling out to amma. There are times when she is cleaning the vessels or sweeping the yard, that she would hear that call. She would look up eagerly, only to realize nobody had called her. Writing erases pain Writing offers her relief. When she writes, her sorrows get erased. She has already published three books in Malayalam. She had a small government job. Father was a sweeper at a bank. Mother was a housewife. After finishing his work, in the afternoon, her father would go to pick jackfruit leaves which he would bundle up and take to the market to sell. Her most cherished moments were when she and her mother joined him to help pack up the leaves and carry those to the market. Radhamani had to displease her parents when she decided to marry her childhood friend, Raj. Both families objected. But the couple stuck to their decision. Radhamani and Raj had their first son nine years after marriage. They named him after the poet they both loved — Shelley. Two years later was born the second son — Sherry. The boys were a little late to start talking. When Shelley was three and half, their regular doctor felt something was wrong and recommended admission to a larger hospital. Both children were diagnosed to be autistic. The parents were advised to pray. “I realized the truth that they would need my help to go through life. Gradually I regained strength.” Radhamani had no option. By this time, her father was dead. Radhamani’s family returned to live with her mother. When both of them left for work, Radhamani’s mother would look after the boys. “The boys would be at a special school until the afternoon. Then mother would feed them and take care of them.” Waking up to cruel reality Radhamani’s world collapsed when her mother passed away. That’s when she came to know firsthand how tough it was to bring up the boys. When the boys were 8 and 6 respectively, a heart attack claimed Raj. That shock haunted Radhamani for a long time. Now, it has been 25 years since he moved on. She learnt that the boys had no clue about death when the family went through Raj’s cremation rituals. They were in no position to do whatever they were expected to do as sons. That whole night Radhamani spent crying. “I know when I die my sons will forget me within a week,” Radhamani states calmly. “Yet when I go out somewhere, they would be waiting at home. Waiting in the hope that I would get something to eat. That waiting is enough for me to live on. Else I would have taken my life long ago.” Finding refuge in words People tell her death lurks in her stories and poems. Radhamani knows. “It is my writing that keeps the thoughts of suicide away. That is why my writing smells of death.” “After I die, someone should adopt my children. I hope the government opens a facility to take care of such children in every district. That is my appeal, my prayer. Then I can die in peace.” This is based on a report dated May 14, 2023, in the Malayalam newspaper Mathrubhumi, written by Sajna Alungal. Illustration based on images accompanying the story.

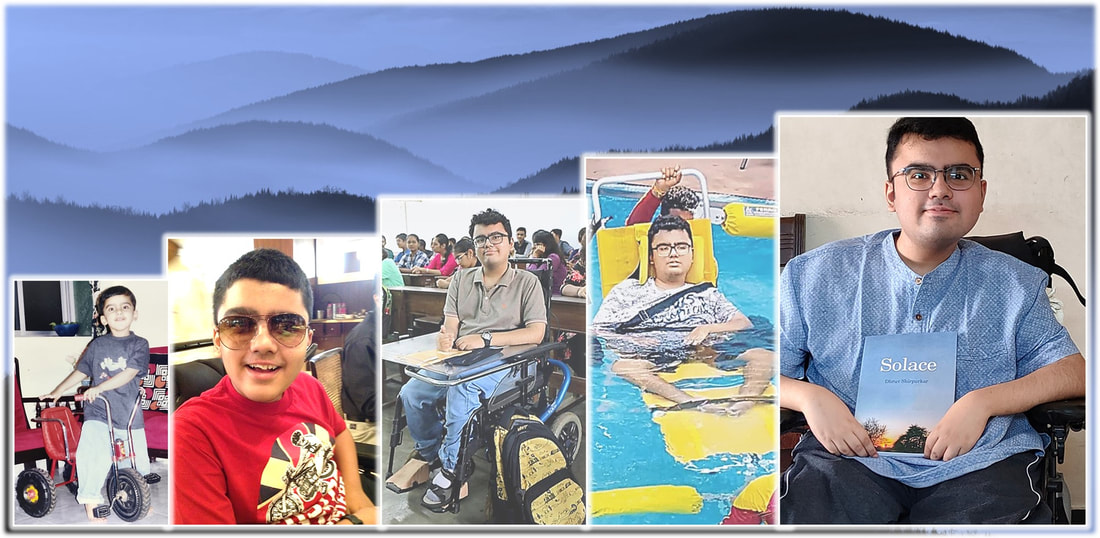

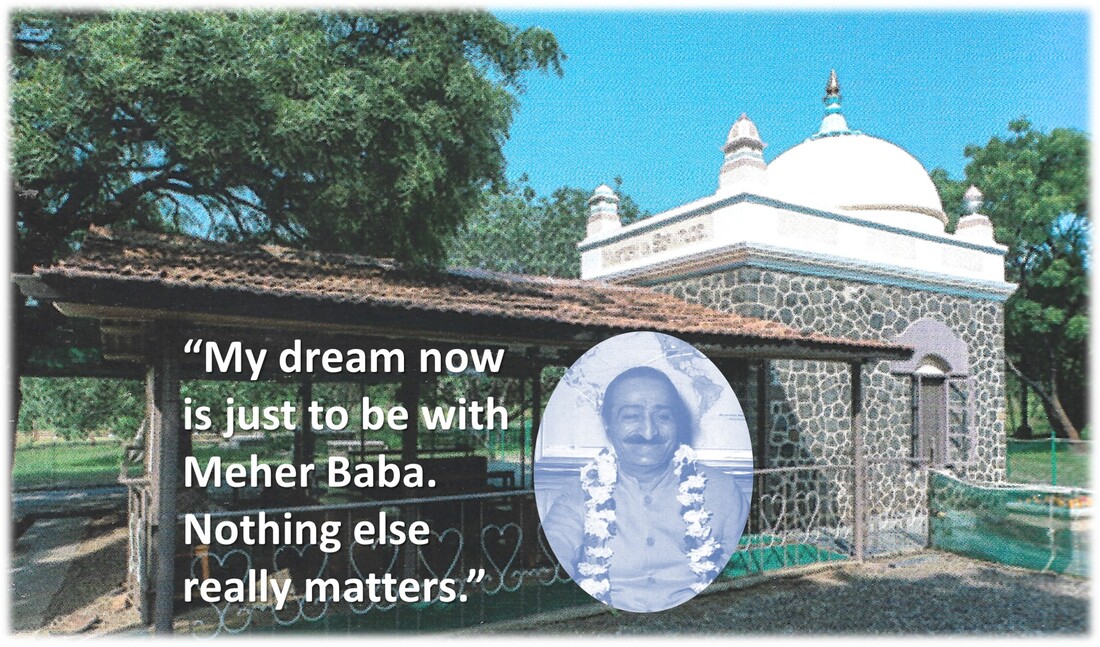

A child was born to the Shirpurkars in November 2000. It was a joyous occasion for family and friends. Then came the time for the child to toddle around. Something was wrong, the parents thought. He was falling more than walking. He struggled to maintain his balance. Soon came the diagnosis. He had a rare genetic disorder: Duchenne muscular dystrophy. His muscles would continue to waste away. There is no cure. It was not easy to find a school that would accept him and his companion disabilities. “Inclusion must start in school. Else, discrimination will persist. My teachers played the most important role in my life, preparing me for all that I have ever done and will do in my life.” He would go on to graduate in Economics. “I wanted to do Engineering, if only to prove a point to those who tried to dissuade me, given my condition. Then I thought about it and chose my favourite social science—Economics.” He was a brand ambassador for the first Wheelchair Accessible Beach Festival in India in 2017. He is associated with an NGO working for inclusion of disabled individuals. He has been a blogger right from the age of 13. “I enjoyed writing while in school. My early efforts were rather immature. But I kept at it as a hobby. In college, English was a compulsory subject, including blog writing. That led to my current blog.” And at 22, Dhruv Shirpurkar has just published his first book, Solace. “After I managed to finish my graduation, blogging became a full-time profession. Wrote more. Readership improved. Gave me confidence. Why not write a book? Publishers and agents were taking too long. Given my health condition, it was wise not to delay. Another bout of pneumonia and anything could happen. So, I went ahead and self-published my dream project, this book.” We matterThis book is a collection of the random thoughts of a young writer who is disabled in body, not in mind. His thoughts force all of us to think. In his introduction to the book, Dhruv makes it clear that the book is not his biography. “I have not done anything extraordinary in my life, but it is more of a book that is meant to help others.” Until recently, he was quite bothered that he had not done anything extraordinary. He suspects many of his readers might have the same concern. This is what he wants to tell them: “It doesn’t really matter what we have done and what we have not done in life. We all have some role to play in God’s divine plan whether we know it or not, whether we believe it or not. We are all worthy and we matter.” My disability is not my identity

Inclusion must start in schoolDhruv remembers looking for a school as a painful phase for him and his parents. Many schools were unequipped for a student like him. Many were unwilling. After a long and frustrating search, Nalanda Public School accepted him. “Thankfully my school was very inclusive.” He narrates a school incident in the book. He had gone to the washroom (with his attendant). His classmates were making a lot of noise. The teacher punished them by making them hold their ears. When Dhruv returned, he was excused from the punishment as he was not present. Later, his angry classmates passed some insensitive comments. “If this is the privilege he gets, then even we will also come on a wheelchair and pretend to be disabled, so that we will be excused,” someone said. Dhruv angrily responded, which worsened the situation. Then, one of Dhruv’s favourite teachers stepped in. She made everyone understand that they were all classmates with inherent differences that all should accept. She went on to encourage everyone to speak up about their grievances, just to clear the air. “My teachers have really taught me what it is to love someone unconditionally even though that person may not be related to you. If you cannot love your fellow human beings, then you have achieved nothing in life. This is what made my schooling the most extraordinary experience of my life. It truly makes me feel that I did not just go to a school of education, I went to a school of life.” It is positive to let goIt is not easy for many, especially the members of a disabled person’s family to accept that the problem cannot be resolved. Yet, in hope and in desperation, they keep trying, even resorting to “pseudoscience”. In his book, Dhruv suggests that leaving hope is not bad. “Sometimes you have to stop hoping for something better and start living. Leaving hope is not bad if it allows you to take control of your life. It allows you to bring change. It guarantees success, something hope won't. You underestimate yourself thinking change will come. You are the source of change, and everything is in you. A change will come only if you work towards it. Otherwise, you are hoping for a miracle and miracles are not miracles if they are expected. Positive attitude involves letting go when you know there is no point hoping. So, stop hoping and start living.” The idea of deathWhat does he think of death? Dhruv is calm and clear when he shares his thoughts during a conversation. His idea of death is simple. “We accept death for others, not for ourselves and not for others without whom we cannot live." His medical condition forced him to ponder about death right from puberty. “Unlike what was expected out of me, I did not develop negative emotions about it. Instead, I came to the conclusion that there is no point struggling with it. I decided to accept it and forget about it. Not about the event itself, but about its consequences.” Is he comfortable talking about death? “Yes. But I am conscious of speaking about it because of the way people respond to it. This response is dictated by their belief that I have certain negative emotions attached with it and I have not accepted it.” He compares dying to growing. “One doesn’t know while growing what good will come of it until he experiences it. I also do not know what good will come out of it. A child plans what he or she is going to do in life with the conviction that nothing is going to deter him or her from achieving those goals. However, the child cannot see the future. This is how I like to think about death.” Solace has moreSolace has more to make the reader think and smile. Like the personality sketch of a cool cat. The reason why the microwave went on strike. Then there are some interesting poems. There are also some profound thoughts on spirituality. The book may or may not occupy the pride of place on your bookshelf. But you will want to keep it within reach so that you can connect to Dhruv whenever life throws a seemingly insurmountable obstacle at you. His approach and words might help you overcome and move on. Dhruv wants his readers to “hold on, continue on your journey and don’t listen to anyone else when your heart calls out to you.” A website had run Dhruv’s story under the headline, “Don't look at him with pity; look up to him for his grit.” If this book makes you shun sympathy and embrace resolve without fearing failure, Dhruv would have succeeded in his mission to help you succeed. After all, he wrote this book for you. To buy your copy of the book, please write to Dhruv at [email protected].

Image credits: Dhruv Shirpurkar; Rediff.com; Mid-day.com THE UNSEEN FACES SERIES 6. DR KHURSHID BHALLA I reached the hall a little late. Given that it was the first annual day celebration of “doctor foundation”, I expected to disturb the speech of some important physician, while the other doctors on the dais frowned at the latecomer. Instead, I found a lovely dance by children in progress, all energy and rhythm. Then came another, where the young choreographer (“a volunteer” the emcee said), was also a participant. Distribution of certificates to those who had completed a beautician’s course (“conducted by an employee”) followed. As I began to wonder if I was at the right venue, I looked around at the audience. They were mainly children, all dressed for a special occasion. They were restless and happy, with my immediate neighbour bouncing up and down on his seat, enjoying the music. He looked at me as if asking why I was not joining him in the celebration. The lone photographer was having a difficult time protecting his tripod from those constantly running to a better seat. Just then, the person who had invited me appeared on the stage. The applause told me she was a favourite of the audience. After all, she was the popular “Bhalla Madam”— Dr. Khurshid Bhalla, Founder Trustee of The Doctor Foundation. Facilitating the miracle of birthYoung Khurshid was always sure she would become a doctor. Her father, the late Maj Gen Dhunjishaw Doctor, had served as the Commanding Officer of a number of military hospitals across the country. That exposure, and her love for children presented paediatrics as a good option. Until a child’s death made her change her mind. “During my internship, I happened to witness the death of a child who had been admitted to the hospital just four days previously. I was shaken up by that death. To me, it was grossly unfair that such a small child should die, even when he was undergoing treatment in a hospital and the paediatrician on duty was close by,” she remembered. She turned to gynaecology and obstetrics. “I thought I would be happier dealing with birth. For me, every birth remains a miracle.” Dr Khurshid Bhalla, now 65, retains her love for children, though she has not helped deliver a baby for several years. Instead, at the helm of The Doctor Foundation (named after her father), she is today on the threshold of a new era in community care, going beyond medicine. Unfit for the business of careShe had the option of working with a private hospital or setting up her own clinic. Yet she has spent most of her life working for charitable organizations. Why? “It is not that I did not try,” Dr Bhalla explained. “I did set up a small clinic in Pune. There I would carefully examine the patients who came, hear them out and then prescribe the test or medicine that they required. I would charge about ten rupees per patient. I thought it was my duty to help the poor and serve them at a price they could afford. I was naive enough to think my model clinic would help a lot of people in the locality. Instead, they simply stopped coming. And my nurse, who was my assistant, told me unless I started giving injections and tablets, no one would come. So, that was that. Obviously, I was not cut out for the business side of care and I could not afford to keep the clinic open.” In 1996, she joined Care India Medical Society, a trust that provided a social support system in the prevention, early detection and terminal care aspects of cancer management. “Care India’s clinic where I worked was surrounded by homes of the underprivileged. HIV infection was rampant. A few years after I joined, I came across many HIV patients and their families,” Dr Bhalla remembered. During those years, HIV infection was almost a certain death sentence. Many mothers lost their children; young wives their husbands. “I would visit the women at home and try to help. Some NGOs came forward to adopt some of the orphaned children. There was one shelter in the outskirts of Pune that took in HIV patients. They had zero facilities. Often the watchman, out of compassion, would bring rice and dal from his house to feed the patients.” It was quite common to simply abandon HIV patients on the streets. “I heard many horror stories of patients curling up on the road all alone. When they vomited or had diarrhoea, they would drag themselves a little away from the filth, helpless and miserable. I knew this was cruel reality and not just fiction, when I heard a social worker casually announcing how she had abandoned her husband, who was in the final stages of AIDS, outside their house before she came to work.” Serving the imprisonedAs part of Care India’s work, Dr Bhalla used to visit Yerwada jail in Pune to examine women inmates. “The jail authorities were surprised that I mingled closely with the women. For me, they were simply human beings who needed care. Some of them were overcome because someone from ‘outside’ was willing to touch them, talk to them.” Dr Bhalla was shocked to learn that some of the HIV-infected prisoners, whose terms were over, refused to leave the jail. They would plead to remain in prison. “Where else would we go? Our families do not want us.” One ex-inmate settled under a tree a little away from the prison. The police decided to force the issue and took him to his house and browbeat the family into accepting him. After all, he was the owner of the house. That didn’t work. The next day he was back under the tree. Finding a new pathThen Dr Bhalla got an opportunity to extend her work in HIV. In 2004, she joined Mukta, set up by Pathfinder International, funded by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. She started work in Budhwar Peth, where most of Pune’s sex workers continue to live and work. “There were about 3,800 women living within one km radius. Initially as I tried to connect to them, I understood that they had the same story—mouths to feed. And as they put it, ‘after the first time, it gets easier.’” They did not want to be tested for HIV. “What’s the point?” they would ask me. “If we have the disease, we are going to die, test or no test. We would rather die without knowing.” It took a long time for things to improve. Things eased once antiretroviral therapy (ART) arrived on the scene. HIV infection was no longer a death sentence. Dr Bhalla considers the 10 years with Mukta a great learning experience in helping the community scientifically. “We had some of the best trainers working with us. For the first time, I found myself hopping into a bus and travelling to unknown villages to set up a network of clinics. I never considered myself a teacher. That stint taught me to be a trainer, to work with a team, to share the commitment so that more people could benefit.” After Mukta, Dr Bhalla returned to head the charitable chemotherapy unit of Care India Medical Society for a few years. Be compassionate, not emotionalWhen it comes to palliative care, the norm is “detached attachment”. You should be fully attached when you are there with the patient, but detach yourself later. This ensures you don’t carry a baggage of interminable worries, fears and sorrows home. “I know that I am a softie. But I can’t help being fully attached to my patient. Yes, I have been a victim of compassion fatigue more than once. But that’s who I am. I always say that I have more friends up there (in the heavens) than down here,” Dr Bhalla confesses. A 10-year old boy with cancer of the bone was Dr Bhalla’s patient when she was at Care India. He was the only son of a mother with three daughters. Once the doctors were discussing his case with the mother. After all the tests, they had concluded that the only option was to amputate the affected arm. They announced this to the mother. “They ignored the boy who was in the room with them. As soon as he heard the verdict, he jumped up and ran out, screaming. I was very upset. That was not the way to break the news. They treated the boy as if he didn’t exist. I was determined to make amends,” Dr Bhalla remembered. Despite warnings from her senior, she took personal responsibility for the child. “If he were my son,” Dr Bhalla told his mother, “I would try to save the arm.” She took the boy to Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai. There she found that there was a procedure to excise the affected portion and spare the arm. With the mother’s permission, Dr Bhalla got the surgery done in Pune. “I felt vindicated. The family was happy. But the joy did not last too long. The cancer returned. The boy was in severe pain. Then he died,” Dr Bhalla was distressed to recollect the case. “Finally, I understood why my boss was cautious. There had been a similar case where they had opted for the amputation. That boy was now doing well and was a regular participant in the NGO’s cultural programmes. It was a painful but necessary lesson. You must be compassionate, but being emotional can cloud your judgment.” Dr Bhalla regrets that compassion is largely missing today. “When my father was dying of cancer, several doctors were treating him and would come to meet him every day. He always looked forward to these meetings. Then they stopped coming. He would often ask us why they hadn’t come. Finally, the truth dawned. There was no treatment left for my father. What would they tell him? It was perhaps embarrassing to tell him that there was nothing more they could do. Looking back, I think even I failed my father as a doctor. Like the others, at that time I too did not know how to talk of death.” Caring for the communityIt is 2 a.m. The family has gathered around the bed of the dying elder. It is clear the end is near. The family has been prepared. Nevertheless, a call is made. After putting the phone away, Dr Bhalla gets ready quickly. Her scooter takes her to the house through empty streets, where “the stray dogs are my only companions”. She arrives and peace descends. She sits with the family until the end. She checks the patient one last time, leaves whispered instructions, consoles the family and goes back home. “This is something I have been doing for a long time. Many of my patients are the elderly or terminal. I spend time with them and the family. It is a privilege to be with them during the last moments. Nothing happens medically; a lot happens emotionally.” Is this a service under The Doctor Foundation? “Yes, it falls under my free home visits,” Dr Bhalla said. Walk into the Foundation’s clinic at Bhawani Peth in the evening and you are likely to encounter boys and girls learning to dance, young women learning to be beauticians, a tuition class and a couple of sewing machines that used to train would-be tailors until recently. Aren’t these rather strange engagements for The Doctor Foundation, headed by a medical doctor? “The Doctor Foundation’s objectives are rather broad, but the main goal is medical care,” Dr Bhalla explained. “We were registered in 2013 and started out with home visits in 2015. We started this clinic in 2016 and opened another in Kondhwa (another locality in Pune) in 2017. I am fortunate to have a team of doctors, mainly specialists, offering their services at the clinic on different days. The idea is to offer professional medical service at a nominal cost. Why should the poor be denied the service of a medical specialist just because they cannot afford it?” And the dancing children? “My original idea was a care and community centre for the elderly. We ended up attracting more children from the neighbourhood. In any case, once we finished with the patients during the day, the entire space was available. Why not put it to use? “An NGO donated sewing machines to teach the women in the community. Somehow, tailoring seems to have fallen out of favour, and so the machines are now idle. Then we had a part-time choreographer come in, keen to teach the boys and girls dancing. He is a big hit now! We also had an employee who was already qualified, volunteering to conduct a beautician’s course. Then a couple who takes tuitions free of cost for poor children asked me if they could conduct their classes here. So, we have a lot of young people coming to the clinic and, in my view, that really energizes the place,” Dr Bhalla said. That explained the dance performances I saw at the annual day celebration. “I thought it was a great opportunity for the children to showcase their talent. The money for hiring the hall was donated by a well-wisher. In fact, the Foundation has not spent on a single piece of furniture you see here. Some came from my house; others are kind gifts from various people. I prefer to spend only on essential overheads. The rest is all for the patients,” Dr Bhalla was very clear. Plans to do moreSo far, Dr Bhalla and her team of visiting specialists have cared for more than 5,000 patients across the two clinics. She is very keen that the Foundation does more. Her wish list for The Doctor Foundation has three main items. Set up a network of partner clinics. She wants to identify clinics that provide ethical, efficient service to patients and make them Preferred Partners of the Foundation. “I would like to begin with Pune and then spread to other districts.” Improve the home care programme. Recruit the minimum essential team and train them. “I have a couple of old cars lying around. I will be happy to begin with those.” Set up a hybrid home. “It will be a home for the elderly to begin with. Then I would like to add on an orphanage for children. I think the young and the old will provide each other very healthy company. It will be a happy home for both. They will not be just put there; they will want to be there.” Would the plans be commercially viable? “I am counting on cross-subsidization. Those who can afford to pay will get better facilities. In the process they will help us serve more poor patients. The service quality will be the same.” Dr Bhalla is positive her dreams would come true. Dr Bhalla is grateful to her fellow trustees for helping her set up The Doctor Foundation. “It has given my life purpose. I have a good reason to wake up every morning.” She also thanks her fellow doctors, the specialists who spare the time for The Doctor Foundation. “It is hardly remunerative for them. But they do it in the spirit of giving back.” Several hundred beneficiaries may not understand the intricacies of a trust. They are simply grateful that Bhalla Madam will hear them out and tell them what is wrong with them. They know she is on their side. And she always has the time to sit with them and hold their hand. … and they went back and lived |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed