|

What if there was an agency that could kill whoever you wanted at a bargain rate? The more you want dead, the less you have to pay. How long would your list be so that you can make the most of the bargain?

It was not easy for Peter, the central character in Neil Gaiman’s short story, “We can get them for you wholesale” to find an assassination agency. Finally, he found one and went on to have a meeting with one of the sales guys from the firm. Peter wanted to start with one guy in the office who he suspected was having an affair with the woman he was engaged to. Then the sales guy offered a two-for-one deal, just 250 pounds each. After some thought, Peter added the woman’s name. At their next meeting, the sales guy offered an even better deal—an irresistible bulk rate of 450 for 10. Peter took some time to think of the 10, “hunting for wrongs done to him and the people the world would be better off without”. It included his boss, the Physics teacher from school, an annoying TV newsreader and a neighbour with a yappy dog. After the list of 10 was ready, Peter was very satisfied with “an evening’s work well done”. He enjoyed the feeling of power he felt as he tightly clutched the list deep in his pocket right through work the next day. At the next meeting, the sales guy mentioned more enticing offers. Finally, irresistibly drawn down the path of better bargains, Peter asked how much it would cost to kill everybody in the world. “Nothing,” came the answer. “We’ve been ready for a long time. We just had to be asked.” Peter was mulling over what that meant when he heard cries all around and a soft knock on the door. Usually, I drop off to sleep after I complete a few pages of the book I am reading. After this story, I was wide awake, thinking of the people who might employ such an assassination firm.

They have been ready for a long time. And so many of us have already asked them. How long do we ignore the knock at our door?

0 Comments

Procrastination is how you make the most of your time. While you are at it, do thieve some to enjoy yourself. After all, I have just about 800 left and you too have not much left, given that each of us has 4000 weeks, give or take a few. That’s Oliver Burkeman’s estimate. Just that number immediately tells us what really matters, what is precious. TIME! So, you have your ways (prescribed and digital) to tame time, you think? “The more you struggle to control it, to make it conform to your agenda, the further it slips from your control,” says Burkeman in his famous book, Four Thousand Weeks. The problem, he says, is that time management techniques don’t acknowledge that time is limited. When you try to manage it, you no longer enjoy it. Time was when we worked by the sun. Rise, shine and set, all with the sun. Then came the industrial revolution that made time another asset to divide and exploit. Are you among those who pine for a bonus 24 to add to your given 24 in a day? It can be liberating if you accept the limit. “The paradoxical reward for accepting reality’s constraints is that they no longer feel so constraining,” says Burkeman. What if you had all the time in the world to be at your device or at work? After all, there is so much to get done by EOD. Once you accept time is finite, how do you make the most of it? Burkeman has a few suggestions. Know what must be done now, procrastinate or even neglect the rest. Limit what you take up and know you must choose and settle for some. Most importantly, enjoy what you use your time to do. As the author puts it, the only way NOT to waste time is to use some of it "wastefully focused solely on the pleasure of the experience.” Burkeman prescribes giving up some control over time and sharing it with family and friends. You will gain emotional riches when you prioritize the out-of-range, in-person kind human connections over the online. Want to know how well you gel with time? Burkeman suggests four questions to ask yourself:

Accept the answers and get going. Enjoy it while it ticks. Based on Four Thousand Weeks: Time and How You Use it by Oliver Burkeman; Bodley Head, 2021.

She chose hand surgery because she could perform that sitting, confined as she was to her wheelchair. The Sitting Surgeon would go on to give wings to many. Dr Mary Verghese was keen to study obstetrics and gynecology. An accident shattered her dreams and left her a paraplegic. After that she underwent multiple excruciating surgeries so that she could get better at being a surgeon, who could not stand. In Take My Hands Dorothy Clarke Wilson tells The Remarkable Story of Dr Mary Verghese of Vellore. Here are some extracts from the book that reveal what a struggle it was for Dr Mary to recover from two spinal surgeries. The [first] fusion operation was performed on March 14, 1955. Bone chips taken from her hip were inserted between five lumbar vertebrae, in order to effect rigidity. [After the surgery] body encased in two slabs of plaster, either one removable, Mary was again placed on a revolving bed. Twice each day she was turned. In the morning, the nurses would remove the top slab and bathe her. Then, turning her over, they would remove the other slab and bathe her back. For two or three hours she was left lying face down. The back slab was then replaced, and the bed turned to leave her again lying on her back. The procedure was repeated in the evening. It was for the hours of greater freedom twice a day, lying on her face, that Mary lived. Head taped and pillowed, a book lying on a low table below the open bed frame, arms resting on the table, she could read or study. Avidly she read book after book [including] volumes on the causes of nerve paralysis. Immobile, widening horizons Not that the longer periods on her back were wholly wasted. She used them to pray for other people and to strengthen her own spiritual life. She enjoyed the visits of her many friends. She shared the problems of students and nurses, listened eagerly to news of all the latest romances and even tried to promote a few. Friends brought flowers every day, and one doctor even fixed a pot of blossoms under her bed so she could see it when she was lying on her face. Dr. Rambo, the American eye specialist, brought a travel poster of the Jungfrau and fastened it to the wall. 'You need something to widen your horizons,' he told her with a smile. 'This will help.' It did. How it did! It stretched the walls to include unbelievable vistas. The pinnacle of whiteness was like a glimpse of heaven. Reflecting life around Nurse Effie Wallace, as ingenious as she was practical, had attached a mirror to a bar over Mary's head, reflecting not only her face but the trays of food set on her chest, so she could feed herself normally, with her fingers. Even better, the mirror could reflect objects outside the window: the big tree, a bougainvillea bush, people passing along the path towards the leprosy clinic. The second operation was for fusion of her lower thoracic vertebrae, utilizing bone chips taken this time from her leg. Back in her room, Mary began again the weeks of immobility and waiting: the imprisoning slabs of plaster; endless hours on her back; the two shorter periods of respite each day on her face, the open book on the low table beneath her, the pot of flowers a splash of brightness on the bare cement floor; the cheering visitors; the young nurses and student doctors dropping in for advice and gossip; the praying for the needs of others; the sounds of hurrying feet; the reflections of a tree, a garden, striding figures. [Some years later, the aircraft was ready to take off as Dr Mary returned after her Fellowship at the Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, New York.] The doors were closed, the seat belts fastened. The great plane began to move clumsily towards the runway, like a bird out of its proper element … or like a human being intended to run on swift limbs but doomed to lumber on wheels. It came to a stop, shuddered as if in mortal agony, then with a roar burst its bonds, mounted upward into freedom. Mary felt a kindred surge of triumph. She saw far below a huge city shrunk to incredible smallness, a blue expanse dotted with toy ships, then nothing but sunlight and clouds and infinite skies. She closed her eyes in wondering gratitude. I asked for feet, she thought humbly, and I have been given wings. The Mary Varghese Institute of Rehabilitation is part of the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department of the Christian Medical College Vellore. The Mary Verghese Trust that was started by her in 1986 continues to conduct vocational training programs for persons with physical disabilities. In recognition of her contributions to medicine, in particular, to the field of physical rehabilitation in India, Dr Mary Verghese was awarded the Padma Shri by the then President of India, Shri V.V. Giri in 1972. She died in December 1986 at Vellore. Portions extracted from Take My hands: The Remarkable Story of Dr. Mary Verghese of Vellore written by Dorothy Clarke Wilson. © Dorothy Clarke Wilson 1963.

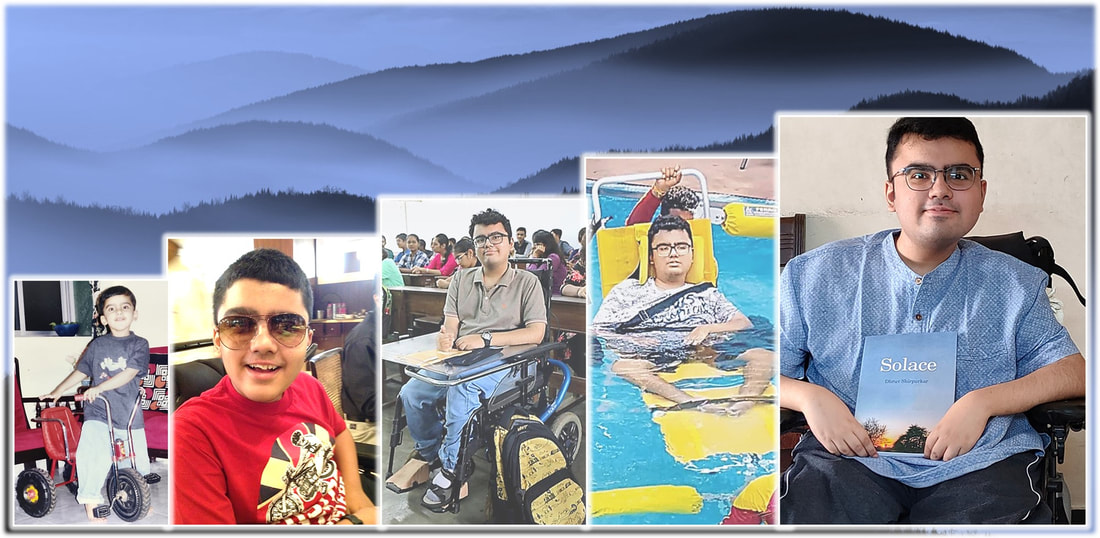

Image of Dr Mary Verghese from https://givecmcv.org/rehab-mela/ Jungfrau Photo by Carol Jeng on Unsplash. A child was born to the Shirpurkars in November 2000. It was a joyous occasion for family and friends. Then came the time for the child to toddle around. Something was wrong, the parents thought. He was falling more than walking. He struggled to maintain his balance. Soon came the diagnosis. He had a rare genetic disorder: Duchenne muscular dystrophy. His muscles would continue to waste away. There is no cure. It was not easy to find a school that would accept him and his companion disabilities. “Inclusion must start in school. Else, discrimination will persist. My teachers played the most important role in my life, preparing me for all that I have ever done and will do in my life.” He would go on to graduate in Economics. “I wanted to do Engineering, if only to prove a point to those who tried to dissuade me, given my condition. Then I thought about it and chose my favourite social science—Economics.” He was a brand ambassador for the first Wheelchair Accessible Beach Festival in India in 2017. He is associated with an NGO working for inclusion of disabled individuals. He has been a blogger right from the age of 13. “I enjoyed writing while in school. My early efforts were rather immature. But I kept at it as a hobby. In college, English was a compulsory subject, including blog writing. That led to my current blog.” And at 22, Dhruv Shirpurkar has just published his first book, Solace. “After I managed to finish my graduation, blogging became a full-time profession. Wrote more. Readership improved. Gave me confidence. Why not write a book? Publishers and agents were taking too long. Given my health condition, it was wise not to delay. Another bout of pneumonia and anything could happen. So, I went ahead and self-published my dream project, this book.” We matterThis book is a collection of the random thoughts of a young writer who is disabled in body, not in mind. His thoughts force all of us to think. In his introduction to the book, Dhruv makes it clear that the book is not his biography. “I have not done anything extraordinary in my life, but it is more of a book that is meant to help others.” Until recently, he was quite bothered that he had not done anything extraordinary. He suspects many of his readers might have the same concern. This is what he wants to tell them: “It doesn’t really matter what we have done and what we have not done in life. We all have some role to play in God’s divine plan whether we know it or not, whether we believe it or not. We are all worthy and we matter.” My disability is not my identity

Inclusion must start in schoolDhruv remembers looking for a school as a painful phase for him and his parents. Many schools were unequipped for a student like him. Many were unwilling. After a long and frustrating search, Nalanda Public School accepted him. “Thankfully my school was very inclusive.” He narrates a school incident in the book. He had gone to the washroom (with his attendant). His classmates were making a lot of noise. The teacher punished them by making them hold their ears. When Dhruv returned, he was excused from the punishment as he was not present. Later, his angry classmates passed some insensitive comments. “If this is the privilege he gets, then even we will also come on a wheelchair and pretend to be disabled, so that we will be excused,” someone said. Dhruv angrily responded, which worsened the situation. Then, one of Dhruv’s favourite teachers stepped in. She made everyone understand that they were all classmates with inherent differences that all should accept. She went on to encourage everyone to speak up about their grievances, just to clear the air. “My teachers have really taught me what it is to love someone unconditionally even though that person may not be related to you. If you cannot love your fellow human beings, then you have achieved nothing in life. This is what made my schooling the most extraordinary experience of my life. It truly makes me feel that I did not just go to a school of education, I went to a school of life.” It is positive to let goIt is not easy for many, especially the members of a disabled person’s family to accept that the problem cannot be resolved. Yet, in hope and in desperation, they keep trying, even resorting to “pseudoscience”. In his book, Dhruv suggests that leaving hope is not bad. “Sometimes you have to stop hoping for something better and start living. Leaving hope is not bad if it allows you to take control of your life. It allows you to bring change. It guarantees success, something hope won't. You underestimate yourself thinking change will come. You are the source of change, and everything is in you. A change will come only if you work towards it. Otherwise, you are hoping for a miracle and miracles are not miracles if they are expected. Positive attitude involves letting go when you know there is no point hoping. So, stop hoping and start living.” The idea of deathWhat does he think of death? Dhruv is calm and clear when he shares his thoughts during a conversation. His idea of death is simple. “We accept death for others, not for ourselves and not for others without whom we cannot live." His medical condition forced him to ponder about death right from puberty. “Unlike what was expected out of me, I did not develop negative emotions about it. Instead, I came to the conclusion that there is no point struggling with it. I decided to accept it and forget about it. Not about the event itself, but about its consequences.” Is he comfortable talking about death? “Yes. But I am conscious of speaking about it because of the way people respond to it. This response is dictated by their belief that I have certain negative emotions attached with it and I have not accepted it.” He compares dying to growing. “One doesn’t know while growing what good will come of it until he experiences it. I also do not know what good will come out of it. A child plans what he or she is going to do in life with the conviction that nothing is going to deter him or her from achieving those goals. However, the child cannot see the future. This is how I like to think about death.” Solace has moreSolace has more to make the reader think and smile. Like the personality sketch of a cool cat. The reason why the microwave went on strike. Then there are some interesting poems. There are also some profound thoughts on spirituality. The book may or may not occupy the pride of place on your bookshelf. But you will want to keep it within reach so that you can connect to Dhruv whenever life throws a seemingly insurmountable obstacle at you. His approach and words might help you overcome and move on. Dhruv wants his readers to “hold on, continue on your journey and don’t listen to anyone else when your heart calls out to you.” A website had run Dhruv’s story under the headline, “Don't look at him with pity; look up to him for his grit.” If this book makes you shun sympathy and embrace resolve without fearing failure, Dhruv would have succeeded in his mission to help you succeed. After all, he wrote this book for you. To buy your copy of the book, please write to Dhruv at [email protected].

Image credits: Dhruv Shirpurkar; Rediff.com; Mid-day.com How do you deal with cancer? What do you say and what do you want to hear? When you are the patient and when you are a dear one? Do you cling on or let go? Do you deny or accept? This is how Reacher's mother and her two sons (Jack and Joe) spoke about her impending death. In what is probably a goodbye meeting with her sons, she talks about her cancer that is about to take her away. It is not an easy conversation. Yet, it is just the kind of "death literacy" conversation that Dr M R Rajagopal advocates. This was written some years ago, soon after I finished reading Lee Child's book, The Enemy. After I recently watched the Amazon series on Jack Reacher, I revisited the blog. I have extracted what is relevant to this post and introduced subheads. The text I have added is in italics or within square brackets. Thank you, Lee, for permission to use this very real and touching part of your exciting work. After hearing from her doctor that she was dying, Jack Reacher and his brother Joe are in Paris to meet their mother. They know something is wrong, they know about an accident. This description is in Jack’s words. We heard slow shuffling steps inside the apartment and a long moment later my mother opened the door. She was very thin and very grey and very stooped and she looked about a hundred years older than the last time I had seen her. She had a long heavy plaster cast on her left leg and she was leaning on an aluminium walker. Her hands were gripping it hard and I could see bones and veins and tendons standing out. She was trembling. Her skin looked translucent. Only her eyes were the same as I remembered them. They were blue and merry and filled with amusement. ‘My boys,’ she said. ‘Just look at the two of you.’ She spoke slowly and breathlessly but she was smiling a happy smile. We stepped up and hugged her. She felt cold and frail and insubstantial. She felt like she weighed less than her aluminium walker. She turned the walker around with short clumsy movements and shuffled back through the hallway. She was panting and wheezing. I stepped in after her. Joe closed the door and followed me. My mother made her way to a sofa and backed up to it slowly and dropped herself into it. She seemed to disappear in its depth. ‘What happened?’ I asked again. She wouldn’t answer. She just waved the enquiry away with an impatient movement of her hand. Joe and I sat down, side by side. ‘You’re going to have to tell us,” I said. ‘We came all this way,’ Joe said. ‘I thought you were just visiting,’ she said. ‘No, you didn’t,’ I said. They find outShe had broken her leg when a car hit her. Then the X-ray revealed that she had cancer. Nobody spoke for a long time. ‘But you already knew,’ I said. She smiled at me, like she always did. ‘Yes, darling,’ she said. ‘I already knew.’ ‘For how long?’ ‘For a year,’ she said. Nobody spoke. ‘What sort of cancer?’ Joe said. ‘Every sort there is, now.’ ‘Is it treatable?’ She just shook her head. ‘Was it treatable?’ ‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘I didn’t ask.’ ‘What were the symptoms?’ ‘I had stomach aches. I had no appetite.’ ‘Then it spread?’ ‘Now I hurt all over. It’s in my bones. And this stupid leg doesn’t help.’ ‘Why didn’t you tell us?’ She shrugged. Gallic, feminine, obstinate. ‘What was to tell?’ she said. ‘Why didn’t you go to the doctor?’ She didn’t answer for a time. ‘I’m tired,’ she said. ‘Of what?’ Joe said. ‘Life?’ She smiled. ‘No, Joe. I mean I’m tired. It’s late and I need to go to bed, is what I mean. We’ll talk some more tomorrow. I promise. Don’t let’s have a lot of fuss now.’ We let her go to bed. We had to. We had no choice. She was the most stubborn woman imaginable. She's only sixtyThe two brothers found her refrigerator “stocked with the kind of things that wouldn’t interest a woman with no appetite.” They started talking. ‘What do you think?’ Joe asked me. ‘I think she’s dying,’ I said. ‘That’s why we came, after all.’ ‘Can we make her get treatment?’ ‘It’s too late. It would be a waste of time. And we can’t make her do anything. When could anyone make her do what she didn’t want to?’ ‘Why doesn’t she want to?’ ‘I don’t know.’ He just looked at me. ‘She’s a fatalist,’ I said. ‘She’s only sixty years old.’ I nodded. She had made up her guest room with clean fresh sheets and towels and she had put flowers in bone china vases on the night stands. It was a small fragrant room full of two twin beds. I pictured her struggling around with her walker fighting with duvets, folding corners, smoothing things out. We’re too late; she made sureNext morning, their mother was still asleep when Jack went and got breakfast. ‘She’s committing suicide,’ Joe said. ‘We can’t let her.’ I said nothing. ‘What?’ he said. ‘If she picked up a gun and held it to her head, wouldn’t you stop her?’ I shrugged. ‘She already put the gun to her head. She pulled the trigger a year ago. We’re too late. She made sure we would be.’ ‘Why?’ ‘We have to wait for her to tell us.’ She told us during a conversation that lasted most of the day. We started over breakfast. She came out of her room, all showered and dressed and looking about as good as a terminal cancer patient with a broken leg and aluminium walker can. The way she took charge spooled us all backwards in time. Joe and I shrank back to skinny kids and she bloomed into the matriarch she had once been. A military wife and mother has a pretty hard time, and some handle it, and some don’t. She always had. Wherever we had lived had been home. She had seen to that. First you live, then you die‘I was ten when the Germans came to Paris. I thought that was the end of the world. I was fourteen when they left. I thought that was the beginning of a new one.’ ‘Every day since then has been a bonus,’ she said. ‘I met your father, I had you boys, I travelled the world. I don’t think there’s a country I haven’t been to.’ ‘I’m French,’ she said. ‘You’re American. There’s a world of difference. An American gets sick, she’s outraged. How dare that happen to her? She must have the fault corrected immediately, at once. But French people understand that first you live, and then you die. It’s not an outrage. It’s something that’s been happening since the dawn of time. It has to happen, don’t you see? If people didn’t die, the world would be an awfully crowded place by now.’ ‘It’s about when you die,’ Joe said. My mother nodded. ‘Yes, it is,’ she said. ‘You die when it’s your time.’ ‘That’s too passive.’ Some battles can't be won‘No, it’s realistic, Joe. It’s about picking your battles. Sure, of course you cure the little things. If you’re in an accident, you get yourself patched up. But some battles can’t be won. Don’t think I didn’t consider this whole thing very carefully. I read books. I spoke to friends. The success rates after the symptoms have already shown themselves are very poor. Five-year survival, ten per cent, twenty per cent, who needs it? And that’s after truly horrible treatments.’ We talked it through, from one direction, then from another. It was a discussion that should have happened a year ago. It was no longer appropriate. I waited for Joe to ask the next obvious question. ‘Won’t you miss us, Mom?’ he asked. ‘Wrong question,’ she said. ‘I’ll be dead. I won’t be missing anything. It’s you that will be missing me. Like you miss your father. Like I miss him. Like I miss my father, and my mother, and my grandparents. It’s a part of life, missing the dead.’ We said nothing. ‘You’re really asking me a different question,’ she said. ‘You’re asking, how can I abandon you? You’re asking, aren’t I concerned with your affairs any more? Don’t I want to see what happens with your lives? Have I lost interest in you?’ We said nothing. ‘I understand,’ she said. ‘Truly, I do. I asked myself the same questions. It’s like walking out of a movie. Being made to walk out of a movie that you’re really enjoying. That’s what worried me about it. I would never know how it turned out. I would never know what happened to you boys in the end, with your lives. I hated that part. But then I realized, obviously I’ll walk out of the movie sooner or later. I mean, nobody lives for ever. I’ll never know how it turns out for you. I’ll never know what happens with your lives. Not in the end. Not even under the best of circumstances. I realized that. Then it didn’t seem to matter so much. It will always be an arbitrary date. It will always leave me wanting more.’ We sat quiet for a spell. ‘How long?’ Joe asked. ‘Not long,’ she said. We said nothing. ‘You don’t need me any more,’ she said. ‘You’re all grown up. My job is done. That’s natural, and that’s good. That’s life. So let me go.’ We owe it to herAs she wanted, they went out to dinner. [We rode a cab part of the way and then walked.] My mother wanted to. She was bundled up in a coat and she was hanging on our arms and moving slow and awkward. But I think she enjoyed the air. We all ordered the same three courses. We ordered a fine red wine. But my mother ate nothing and drank nothing. She just watched us. There was pain showing on her face. Joe and I ate, self-consciously. She talked, exclusively about the past. But there was no sadness. She relived good times. She laughed. ‘Why didn’t you tell us a year ago?’ Joe asked. ‘You know why,’ she said. ‘Because we would have argued,’ I said. She nodded. ‘It was a decision that belonged to me,’ she said. Next morning when Jack woke up he heard Joe talking to the nurse. She told me she was my mother’s private nurse, provided under the terms of an old insurance policy. She told me she normally came in seven days a week, but had missed the day before at my mother’s request. She told me my mother had wanted a day alone with her sons. Later, Joe found Jack getting ready to leave. ‘You leaving?’ he said. ‘We both are. You know that.’ ‘We should stay.’ ‘We came. That’s what she wanted. Now she wants us to go.’ ‘You think?’ I nodded. ‘Last night [at dinner]. It was about saying goodbye. She wants to be left in peace now.’ ‘You can do that?’ ‘It’s what she wants. We owe it to her.’ [At breakfast] my mother had dressed in her best and was acting like a fit young woman temporarily inconvenienced by a broken leg. It must have taken a lot of will, but I guessed that was how she wanted to be remembered. We poured coffee and passed things to each other, politely. It was a civilized meal. Like we used to have, long ago. Like an old family ritual. We left thirty minutes later. We hugged long and hard at the door and we told her we loved her, and she told us she loved us too and she always had. We left her standing there and went down in the tiny elevator and set out on the long walk back to get the airport bus. Our eyes were full of tears and we didn’t talk at all. This is a slightly modified version of the original post, which you can find here.

As I devoured one Lee Child book after another, I got lost in the world of Jack Reacher. He is the Grim Reaper to those who dare to cross him. The large man has an equally large heart intent on doing the right thing. Given all the bone-crunching action in Reacher's world, this part in The Enemy, was a surprise. With Lee Child's gracious permission I reproduced this extract as a tribute to my friends, especially those in palliative care, who deal with death in close proximity almost every day. They try to make every departure, always too soon, as comforting as the movie the dying must leave. Thanks, Lee! Thanks, friends! |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed