|

Mention law and most of us immediately visualise a court-centric complex system populated by lawyers and judges who tackle the incomprehensible rules and provisions populating thousands and thousands of intimidating pages. Now think of a situation where you are helpless, bed-bound and your life (or its peaceful closing) hinges on someone pulling off a legal miracle. Just when you have given up all hope, an advocate reaches out to you and resolves the situation you are facing with a large dose of selfless compassion. What would you call her? A saviour? An angel? A miracle? Well, she prefers to be called Sandhya. Advocate J. Sandhya is a practising lawyer based in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. She is also a social activist, and a former member of the Kerala State Commission for Protection of Child Rights. For the many she has helped and continues to help, she is the humane face of law. Many. Like Maya. And Asha. The rebirth of MayaIt was during the Covid years that a neighbour with the help of a social worker found Maya all alone at her rented home. She was smitten by some disease that had paralysed her. The home was flooded and infested. It was not easy to move her out. When she was admitted to a palliative care facility, Maya was not in a condition to move, talk, or remember anything. After several days of care, including physiotherapy, Maya dodged what had appeared to be lurking round the corner: death. When Advocate Sandhya stepped in, Maya had started to make efforts to talk. The first thing that Sandhya did was go to Maya’s home and shift all her stuff out. The landlord had insisted on this. Which posed a major question. Where would Maya live now? Based on the information Maya gave her, Sandhya contacted Maya’s uncle. He came and but did not wait for too long. He declared (in legalese) that he had nothing to do with Maya and he was not to be called again. It was heartbreaking for all to see Maya’s plight, but Sandhya was not ready to give up. Her conversations with Maya had revealed that Maya’s parent used to work in a prominent central government office. Sandhya contacted the organisation and informed them about Maya. Yes, as the only surviving member of the immediate family, Maya was entitled to a pension, provided there was documentary evidence linking her to the late employee of the organisation. Sandhya had to start from scratch. Painstakingly, she gathered enough evidence to establish Maya’s identity and her connection with the parent. It required a lot of paperwork and plenty of trips to the organisation’s office, all funded by Sandhya. Then, taking pity on their ex-colleague’s daughter, a few compassionate people in the organisation started coming to Sandhya and Maya to help them with the formalities. Finally, the official announcement came: Maya was entitled to a monthly pension of ₹30,000. On the health front, Maya was making very slow progress. But now she was very excited. The pension was giving her a second life. Perhaps she could afford the rent for another house and start all over again. Sandhya said, “For most of us, palliative care signifies that the end of life is very near. Not necessary! Sometimes, we witness miracles. And, with hope and care, some patients like Maya bounce back.” Given Maya’s condition, no one had imagined that she could get a regular income. “My thinking was about getting Maya back on her feet,” Sandhya explained. “From whatever I could gather from Maya, I surmised this pension was a strong possibility. As a lawyer, all I had to do was make a good case for it in terms of documentation. Fortunately, it worked out.” When a scam hit AshaAsha was ill, very ill. All she had as family was her son. Instead of going to school, the son would just hug and sleep with her at the government hospital where she had been admitted. What if she died when he was away? By the time Sandhya stepped in, the mother and son had been in the hospital for more than 40 days. Even if they discharged her, the doctors did not know where they could send her. The advocate managed to crowdsource some funds and get a private sponsor so that Asha could move to a rented house and the son could carry on with his education. Asha and her son moved to a small home. While Asha continued to face challenges with her mobility, life appeared to be slowly getting on track for both of them. But they remained desperate for money. One night, around 1 a.m. Sandhya got a frantic call from Asha. The latter had just received a call from the police cyber cell. They were coming to arrest her for being instrumental in moving one crore rupees of scam money through her bank accounts. Some weeks previously, Asha had received a call from an unknown number offering her commission if she opened new bank accounts and shared the details with them. Given their dire need for income, this was too irresistible a proposal for Asha and her son. Caution stood no chance before desperation. So, the son helped mother visit four different banks on her wheelchair. Of course, neither of them had any idea they were being played. Advocate Sandhya contacted the cyber cell and shared all the information with them, complete with photographs and documents. She made it clear that Asha was not a villain but a helpless victim in poor health. When they insisted on arresting and moving her to the north of India where the scam had originated, Sandhya agreed. However, she warned them that she was unlikely to survive the journey. Today, Asha is about 45. The son is 18 and has completed his ITI course. Her physical and financial struggles have not ended. But Asha is immensely grateful that she has the backing of someone like Sandhya. A little law, much loveSays Dr M R Rajagopal, Chairman Emeritus of Pallium India: “We are grateful to Sandhya for providing voluntary service whenever we seek her support on behalf of poor patients. There is always a sense of urgency when we reach out to her and she would gladly and efficiently help us, mostly by avoiding tedious litigation and by practical mediation.” He cited two instances. A young woman was dying of cancer. Her only daughter, eight years old, was clearly at risk of being harmed by her father from whom she and her mother had been separated for six years. Sandhya approached the Child Welfare Committee of the district. In two days, she managed to obtain an order that granted custody of the girl to the grandmother in the event of the mother’s death. The mother died after five days, in peace. A middle-aged woman, who had been abandoned by her family, was dying of cancer. Her only support was a home nurse, who was looking after her ever since she was diagnosed with the illness. There was every possibility that some member of the estranged family would return to claim the property after she passed away. So, she wanted to prepare a will, leaving her property to the home nurse. Sandhya helped her prepare and sign the document within the limited time that she had left in this world. She too could now leave in peace. Disputes are all too common when life is setting. Not just about division of estate but also about how long one should be kept alive on life support. How long should one extend the suffering of not just the patient but also the members of the family? As a person hovers between life and death, the challenges integral to both get magnified. Often the situation is beyond medicine (and palliative care) and a little practical nudge from someone well versed with the law and its application brings immense relief to all. Sandhya believes that law need not be impersonal and intimidating. “Institutions like Pallium India are doing a wonderful job taking care of health and life. Very often, law can make a significant contribution at the right time. Yes, the knowledge of law is important. More important is the willingness to help and to use one’s skill for the sake of humanity. Anyone can help in one way or another. I just happen to specialise in law and its practical aspects.” May Sandhya inspire more of us to help, one way or another. Names and some identifying details of all beneficiaries of Sandhya’s support have been changed to protect their identity. Image used solely as an illustration.

0 Comments

How would you like a lawyer by your side when you are critically ill? No, not to finetune the will. But to compassionately mediate as you, your family and the doctors struggle to take critical decisions about your very life. Nancy Dubler, the lawyer-turned-bioethicist who “pioneered bedside methods for helping patients, their families and doctors deal with anguishing life-and-death decisions” would have loved to help you. In its tribute to her after she passed away on April 14, The New York Times described her as the “mediator for life’s final moments”. She was 82. Dubler founded the Bioethics Consultation Service at the Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, USA. The Harvard-educated lawyer did this to “level the playing field and amplify nonmedical voices in knotty medical situations.” The team included lawyers, bioethicists and philosophers who carried pagers to alert them about ethical emergencies. In her 1992 book, Ethics on Call: A Medical Ethicist Shows How to Take Charge of Life-and-Death Choices, Dubler observed that modern medical technology “lets us take a body with a massive brain hemorrhage, hook it up to a machine, and keep it nominally ‘alive,’ functioning organs on a bed, without hope of recovery.” And the bioethicists help to untangle the “web of rights and responsibilities that ensnares all patients and caregivers.” Clarity cuts through silence, liesIt was at the end of 2005 that’s Dubler warned about the exponentially increasing conflict in medicine. Nineteen years later, the confusion and the conflicts have only got worse. Economic factors like insurance now play a significant role. As Dubler put it, “The dynamics of the doctor-patient and provider-patient relationships have been deformed by the increasing focus, in fact and in the media, on the cost-containment thrust of both managed care and acute care medicine. There are simply more parties to any decision and thus greater potential for misunderstanding, misinformation, disagreement, and dispute.” In A Hastings Center Special Report on Improving End of Life Care Dubler cites a case when the ICU team requested bioethics mediation because the family was not letting them discuss with the patient about his future care. The patient was alert and aware and had recently been removed from a ventilator. The decision they needed was about placing him back on ventilator in case the need arose. The medical team told Dubler that the patient’s multiple cardiac problems had been “addressed to the maximum medically.” His two sons, loving, devoted and who stayed with the patient, vehemently opposed any such discussion as they felt it would upset their father. The sons knew that their father was very sick but “the independent and proud person” needed hope to go on. Dubler cited studies that established “when family members try to shield the patient from bad news, the patient usually knows the worst, and the silence is often translated into feelings of abandonment.” Finally, they thrashed out a format and Dubler spoke to the patient. After reintroducing herself to the patient who was “clearly very weak and tired,” Dubler asked if he would want his sons to make decisions for him if he was unable to do so. He was also okay with the order of decision-making, the older son first. Then came the important question of whether the patient would be willing to be intubated again if the doctors thought it necessary. The patient said, “I would think about it.” This mediation defused the conflict about sharing information with the patient. At least, the patient and everyone else had a resolution with which they could work. As Dubler observed, “The mediation prevented the bifurcation of family and staff. It was labor intensive, requiring two hours, but it provided clarity going forward.” The tools of bioethics mediationThe bioethics mediator comes “fresh to the facts of the case, impartial to the situation of the case, uninvolved in the prior treatment decisions in the case, and unallied with any party in the particular disagreement.” The process helps the parties to identify their goals and priorities and to generate, explore, and exchange information and options. Of course, the agreement reached must have sufficient and realistic structural supports to become “the reality of care.” As Dubler stated, bioethics mediation helps to:

Conflict in end-of-life decisions can be potentially destructive for surviving family members. Skilled bioethics mediators committed to managing, not banishing, disputes can help to tame some conflicts. In her tribute to Dubler, Nancy Berlinger, a senior research scholar at The Hastings Center, says: “She always kept her eye on the reality of the experiences of being a patient, being a family caregiver, being the clinician in the room, and being responsible for the care of this patient and for discussions with this family. She would remind clinicians of their basic ethical duty—to be faithful to that person in the bed—and would remind bioethicists that when we were discussing ethical challenges, identifying principles, and crafting guidance, the same duty applied to us.” Thank you, Nancy Dubler, for devoting your life to helping many lives depart in peace, without being shrouded in conflict. Reading about Dubler introduced me to the concept of bioethics mediation and raised some questions. Is this practiced in India? Is it part of palliative care? If it is not, should it be? If feasible, should a compassionate lawyer be a part of the team responsible for the patient in the final stages? I am hoping to be educated by my knowledgeable friends in palliative care. Sources

Improving End of Life Care: A Hastings Center Special Report, November - December 2005. The New York Times, May 10, 2024. Image of Nancy Dubler: The Hastings Center. She had recently lost her job. Her family business was sinking. Her father had just been rescued and brought back home safely after yet another unannounced trip outside home, lost in the shadows of dementia. Her mother was struggling to take care of her own health even as she tried her best to look after her husband. And one of the many caretakers who joined and left, had walked away with all the savings of the family.

Then life became a song, several songs, for all of them, at least for a few days. It was not an easy decision, but the daughter decided to take on the additional responsibility of moving her parents to her own place. Steeped as the family was in music, it was but natural for all of them to gather around his bed and sing song after song and play antakshari. The change in the father was very visible. He smiled. Life returned to his eyes. His fingers remained rigidly curved but he would make an attempt to clap whenever he won the singing game. And he did win multiple times because he knew which songs to sing. The musical notes drove away their loneliness. No longer were they two bodies in another corner of the town that others were obliged to look after. There was no changing tomorrow. Today they sang. Then one night the father indicated that he wanted to go home to that lonely house where he lived with his wife. He was insistent. The daughter obliged. A late-night ambulance took them there. All the paraphernalia that had moved with them went back. Tired, the daughter decided to take it easy for a couple of days. Until her mother called. He had stopped trying to talk. Eyes closed. Not moving at all. The daughter rushed. Holding his hand, she called out to him. With great effort, he tried to open his eyes. Apparently, he recognised her. Just one word escaped his mouth: “sing.” And she sang. His favourite song. His face transformed. He was almost smiling. The next day he passed away in peace, at home. Life has pulled her back to its many inevitable chores and testing challenges. But she is unable to fill that gap. She knows somewhere he is listening. And applauding whenever she sings. So, she sings on. Wife: “Does it hurt now?” Husband: “How many times will you ask me? Now this pain will go with me. You take care of Guddi.” Guddi, 10, their daughter, is not very comfortable when he holds her hand. Wife: (Angry) And how do you expect me to do that? The wife accuses him of bringing this calamity on all of them because of his drinking. Guddi looks at both without any expression. Husband: “I wanted to help Sonu finish her college. Now I don’t know ….” The wife bursts out. Grabs Guddi. “And what do you want me to do with this one? Forget me. You are always more worried about your sister. Where is she now? Oh! My fate!” She slaps her forehead. Just then, the doctor walks in with Sonu, the sister. Seeing the sister, Guddi brightens up. Tries to run to her. Mother holds her back. The doctor examines the husband. Then says he has some good news to give. The sister is willing to donate her liver. The husband begins to ask something, but Sonu stops him. Sister: “Let the doctor finish what he is saying.” Doctor: “There are many reasons for liver cirrhosis. Some problems by birth, some virus. But in your case, we all know what the reason is ….” The husband holds his ears in apology and starts sobbing. “Never again.” Doctor: “Like I told you, no treatment will work at this stage. Only a transplant. That too quickly. Fortunately, your sister is a match. And she has agreed, and. Of course, there is no danger—" Sonu suddenly stops doctor. She addresses the patient, her brother. Sister: “The doctor says there is no danger to my life. He says he will take only a small piece of my liver. What I know is I am giving you a piece of my life so that you get a second life. Not for me. But for Bhabhi and Guddi. You were always worried about my college, right? Now you better get well. Because I want you to make sure Guddi completes her college. Remember, you owe it to me.” The wife gets up crying and does a namaste to her sister-in-law. She is unable to speak. Sonu enfolds her and Guddi in an embrace. In the background, the husband, weeping bitterly, does an apologetic namaste to the three. The doctor walks away. Guddi suddenly runs to him and pulls at his coat to stop him. Guddi: “Please don’t take too much of her liver. If you want more, take a little piece of my liver.” The doctor laughs and pats her head. Guddi runs back to the bed, sits, and holds her father’s hand. Her mother and aunt join them. Images by MS Designer Image Creator.

Our last conversation had not gone down well. Here I was again, with a very reluctant and unhappy Jay, waiting for my senior doctor friend to join us. “Listen,” Jay hardly bothered to conceal his anger. “I can understand if you can’t or you don’t want to pay for mausi’s treatment. But no way am I going to submit her to this palliative nonsense. I don’t want to kill her.” I took a deep breath but was spared the need to reply because Dr PC chose that moment to walk in. Jay greeted him politely enough, but I could see it took an effort. For the next half hour, I remained silent while Jay talked about mausi’s condition. Mausi, an orphan, had joined the family decades ago as a house help. Now that everyone else was gone, Jay was effectively an orphan too. They just had each other. I knew Dr PC would first listen before he spoke. Sure enough, by now, Jay had opened up and was telling the doctor about the interactions he had had with her right from his young days. It was obvious she meant the world to him. “Some people,” Jay said, pointedly looking at me, “think that I am trying to make money using her as an excuse. Yes, I don’t have a job and I do not know if and when I will get one. But I am willing to sell every little thing I have. I will beg and borrow. I want her to get better. Just because it is cheap, I do not want to risk her life and give her some—” “—palliative care?” Dr PC completed Jay’s sentence and smiled at him. I thought it was time for me to say something, but Dr PC silenced me with a look. Dr PC asked Jay about the treatment options he had discovered as he had spent very many days hopping from hospital to hospital. As Jay narrated his formal and informal interactions with doctors, Dr PC flipped through her papers. You are doing right “Given her age and her diagnosis,” Dr PC gently placed the file on the table, “I think you are doing the right thing.” Jay was shocked. “But I am not doing anything. At least not yet. Everyone is quoting some exorbitant fees. She has no insurance. Worse, everyone is sure about the charges but no one can give me a guarantee that she would be all right after the treatment.” Dr PC closed his eyes and looked lost in thought. Silence reigned. His eyes still closed, Dr PC described the surgery she would need and the risks involved. Then he spoke about mausi’s likely state if she survived the surgery—how much help she would need if and after she returned home. “Chances are she would need multiple follow-up sessions in the hospital afterwards. Her life would be reduced to hospitals and medicines.” Dr PC opened his eyes and looked at Jay. Jay was on the verge of tears. It was bad enough that no hospital had given him a guarantee. Clearly, no one had told him about what would happen if and when she left the hospital. Dr PC did not wait for Jay to reply. Are you selfish? “I may want to do everything possible, try ayurveda, homeopathy, every system possible to ensure my close relative lives. That’s my need, that’s my responsibility. I am also worried about what others would say. That’s me being selfish,” that was a little shocking coming from Dr PC. But he wasn’t done yet. “I do not think you are selfish, Jay. You would always put what is best for mausi first. Not based on what others may think, but what is best for her, being fully aware of her condition. “You know, when I was a surgeon, I began by learning how to operate. Then I learnt when to operate. But the biggest lesson was what I learnt last—when not to operate. I am happy there are still a few surgeons who are able to see the larger picture from a more humanitarian perspective. Please listen to them.” Dr PC continued. “You and your mausi are so lucky that you have no money. Otherwise, you would not be wasting time with people like us. You would have taken her to the best hospital and got her the best treatment your money could buy. Am I right?” Jay attempted to smile. “And that is something most of us would do. The younger they are, the closer they are to us, we will want to try everything. We tell them they are brave. We want them to fight. We do not think about in what state the fight would leave them.” Dr PC looked pensively at the glass he held. “Medical science is fantastic. I am sitting here before you thanks to the power of medicine. But we need to be conscious of reality. Decide the goal of care depending on the patient and the condition, the diagnosis, the prognosis. Nothing like getting back to good health whether an experienced doctor makes it possible or an efficient robot. The thing is we are not robots. We are vulnerable human beings with fragile emotions. We get sick, we die. We must accept the limits of medicine.” Dr PC told the story of a friend who had passed away recently. “He and his wife had spent more than six decades together, and you know what she regretted the most at the end? That she could not feed him at least one or two spoons of his favourite food before he died. He had managed to gulp down some water even as he struggled to breathe and was then rushed to the hospital. First thing they put on him was the oxygen mask and it never came off for all of the 20 days the tubes kept him alive. The food she had lovingly made stood no chance. Would it have been different if someone had bothered to review the goal of care after a few days, to let her have a say?” The missing department Silence again. Then Jay spoke up in a more mellowed tone. “In all those hospitals I visited there were departments for everything. It was as if there was a department for every organ and every treatment. But I did not find any department for palliative care. Doesn’t that mean palliative care is not really medical science? Maybe something that is outside the limits of medicine like you just mentioned? Something only supposed to make you feel good. Something like a prayer, perhaps?” I winced. How would Dr PC react to this? Dr PC was actually smiling. “So, if at all there is a palliative care department, that is where you go, give up and just die. You think so?” “Maybe,” Jay did not sound very sure. Dr PC resettled himself in the chair. “You know, that is exactly what most people think of palliative care, including doctors. It is something cheap and often charitable. Not serious and professional, right? Not of great value.” Dr PC did not wait for a reply but continued. “Let us talk about mausi for a minute. Is she most comfortable being at home with you?” “Yes, of course.” Jay replied. ‘But she complains of pain. Can’t sleep.” Care that matters Dr PC reached out and held Jay’s hand. “Suppose you are there with her at home. You give her just enough medicines, what the doctor has prescribed, to keep her pain away. And to help her sleep. You ensure she eats when she can, whatever she can keep down comfortably. You know how she hates to just lie in a corner when there are a thousand things to do at home. So, you let her do a few things that will not harm her but make her feel she has some purpose. Let her know that she will need to cope and compromise and that is perfectly alright. Encourage her to talk. Whatever she wants to tell you. You listen. Sometimes she wants to pray, you told me. So, you make available whatever she needs for the ritual that is important to her, for her time with God.” Dr PC let go of Jay’s hand and sat back. “Remember,” Dr PC raised a warning finger, “do not make any false promise at any time. Reassure her that you are there for her.” Dr PC paused and then asked. “You think you can do all of this?” Jay nodded. “When you do all this, you are essentially offering her the essence of palliative care. I know you are not a doctor or a trained in palliative care. But even when you seek help from either of those professionals, you will become their partner in offering the quality of life she deserves. Something that her disease or even some aggressive treatment may deny her. Like I keep saying always think of the goal of our care at this point in time. We must keep revisiting that because things change. She may feel she is fine for days, or she may suddenly deteriorate.” Dr PC waited until Jay looked up. Cheap but invaluable “Now let us talk money. How much do you think this will cost you?” “Not much,” Jay replied. “That’s exactly why you are unlikely to see a big board welcoming you to the Palliative Care Department in what you might call a 5-star hospital.” Dr PC laughed, forcing Jay to join him. “Not many of us can offer affordable treatment in the conventional sense even if you have insurance. But many of us are already offering palliative care totally free or at a nominal cost.” Jay looked more at ease. But he was not convinced yet. “Aren’t we ruling out the possibility of a cure if we opt for palliative care,” he asked. “Let me repeat," Dr PC sighed. "Examine and understand the patient. What are the possibilities? Then decide the immediate goal of care. The goal of care is something dynamic. Palliative care does not have to wait for curative treatment to be over or to fail. It can ease the painful physical and emotional effects of essential treatment. It could be about making a significant adjustment in the treatment plan that would not compromise the outcome but would enhance comfort. Or it could be about being there to hold a hand and offer support. Or it could be about simply adjusting the pillows. After all, it is about respecting one’s right to a good, peaceful quality of life at any stage of life, during or after treatment.” Care, be compassionate I had a sudden brainwave. “I think we should rename palliative care as compassionate care.” I was waiting for applause from Dr PC, but Jay shot me down. “If it is care, it must be compassionate. If it is not compassionate, it can’t be care,” Jay declared, very sure of himself. Dr PC looked at me and laughed. I could only stare at Jay as Dr PC stood up and patted him on the shoulder. “Time we left. Mausi has been alone at home for too long.” After a quick handshake with Dr PC, the new Jay led the way. This is based on real lives and experiences. Thank you Dr M R Rajagopal of Pallium India and Dr Nagesh Simha of Karunashraya for always being ready to educate me about palliative care, (which I would rather call compassionate care.)

Images by MS Designer Image Creator. With change fast and furious as always, how relevant is what your school taught you two or more decades ago? What is it that you have had to or want to unlearn to cope with today? Medscape asked this question recently about medical school. Even before I read the article in full, I shared the same question with a few doctor friends. I expected some finger-wagging about the need to keep up with technology and some frowns at the interfering Dr Google. I also expected doctors in the US and India to come up with different answers. Well, surprise! What Medscape gathered This is the gist of what Medscape gathered.

What my doctor friends said

What have you unlearnt? Yes, apparently robots are wonderful surgeons today. But the patients are not automations. The core message from everywhere appears to be to take time to listen and clasp a hand before the robot takes over.

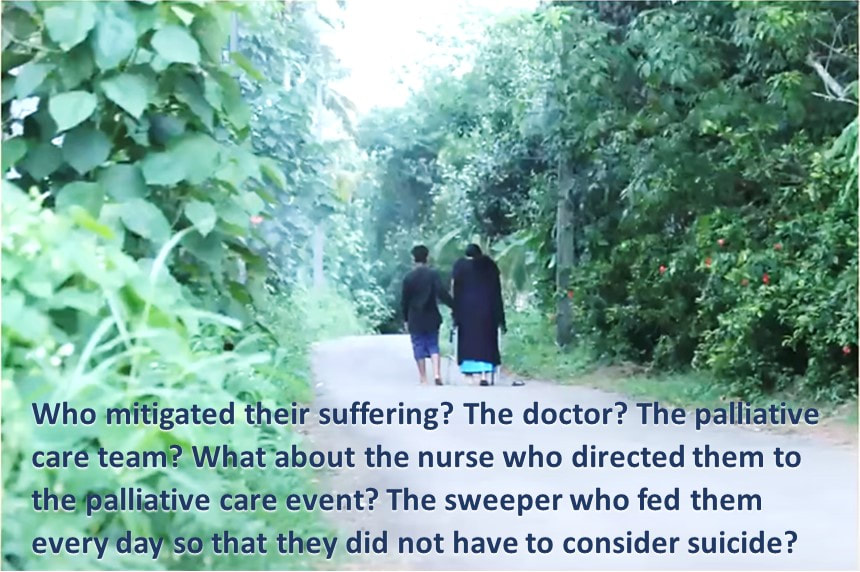

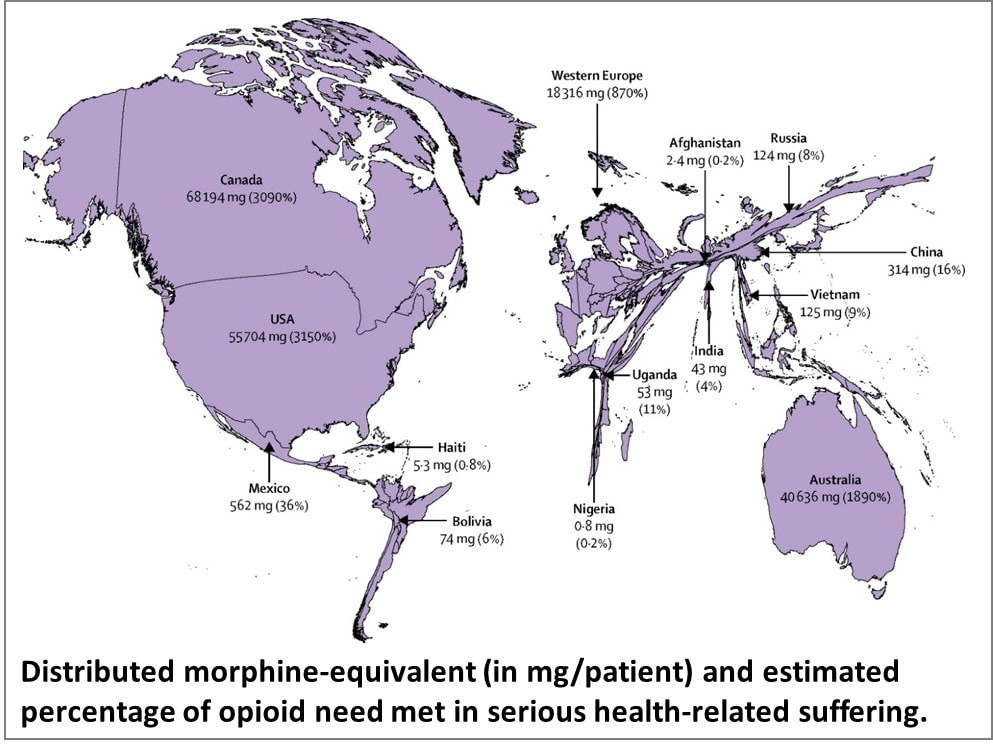

I am grateful to my doctor friends who were kind enough to share their opinion. Special thanks to Dr Srinagesh Simha, Dr Khurshid Bhalla and Dr Pushkar Khair. So much about the medical profession. What about your profession? Is there something you have unlearnt? Is there something that was taught to you decades ago, but you disagree with today? This is inspired by a talk delivered by Dr M R Rajagopal, Emeritus Chairman, Pallium India, as part of the seminar series “Palliative Care and the Motives of Medicine”, organized by the Harvard Medical School Department of Global Health and Social Medicine. This is written in his voice with his permission. The doctors attended to her leg and restored her sight. But were they solely responsible for giving her “life” back to her? What about the sweeper who provided food every day so that she did not have to consider suicide, as her son had suggested? What about the social media support that gave a roof over their heads? What is the motive of medicine? Are we here just to diagnose and treat diseases? Or is it a bit more than that? We may have come into it for different reasons but once we are in the field of medicine, we realize what a huge privilege it is to be part of healthcare. We find ourselves in a position to make the most difference to other people’s lives. We see people at the most vulnerable times in their lives and at times become the instruments to help them rise from the depths and smile again. To actually provide healthcare for all, we may sometimes have to travel over difficult terrain. At times, we have to strike a new path because at the other end there is somebody who belongs to 84% of the global population, without access to quality healthcare. They cannot get to us, we have to reach healthcare to them where they are, when they need it. Does that sound frightening? It takes more than a doctor Ironic as it might sound, I got to meet that helpless mother and son when I was leaving a World Palliative Care Day function. The 12-year-old boy had been sent with the hope that someone would be there at the function to help his mother. Her one leg was fully wrapped in an ugly bandage. And she was blind. She was about 40, a single mother abandoned by her husband. She had been a diabetic since the age of three. Diabetes had stolen her sight four years ago. A surgeon had said she would need an above-knee amputation. Of course, she was in significant pain, “like someone is cutting my leg with an axe.” She lived in a shack that belonged to someone else. She told me about a weekend when they had to starve. Hungry and frustrated, the son said, “Mom, let us kill ourselves. I cannot bear this hunger anymore.” Mom replied, “Son, today is Sunday. Let’s wait. I will find some way.” Somehow, they got across to a healthcare center. Luckily, they found a very humane doctor there who put them up for three months before I got to see them. They survived on the meal provided by a sweeper at the center every morning. They landed at the palliative care day function where I met them first because a kind nurse at the health center had directed them there. A definition distant from reality There are several definitions of palliative care today. Most of us working in the domain abide by what the World Health Organization had stated 21 years ago. Among other things, it prescribes palliative care for those with “life-threatening illness.” Let us go back to the mother we just met. She is diabetic; does she qualify? She is blind; does she qualify? More than anything else, does hunger qualify? The same persistent hunger that almost drove them to suicide? We cannot be rendered helpless by a definition. After all, such definitions tend to come from the 15% of the world that is rich and where all the meticulous studies happen. It gets applied to the 85% of people living in low-and-middle income countries in drastically different conditions. Do such definitions bind or liberate? Let us go back to the fundamental issue. What really is healthcare? When we keep someone’s heart beating, are we providing healthcare? What is the duty of the healthcare provider? The law does not define it in India. But the Indian Council of Medical Research, a statutory body, defines that duty as: “To mitigate suffering. To cure sometimes, to relieve often, and to comfort always.” And the ICMR emphasizes there is no exception to this rule. How many of us are aware of that definition? Do we practice it? Or do we stick to what we learn from the textbooks as dictated by medical institutions in 15% of the world, the high-income world? Palliation as mitigation If you are a healthcare professional and you have not been taught how to mitigate suffering or do not accept it as your primary responsibility, we in palliative care will be happy to help you. Not that we have all the answers. At least, we try. Because mitigating suffering is our primary motive. Opioids are one of the primary tools we use for relief from moderate to severe pain. In 2017, a Lancet Commission Report depicted access to opioids (which translates to access to pain relief) across the world. You can easily make out which country is obese, and which is malnourished when it comes to opioid access. The trick is to strike the right balance between easy availability and the necessary restrictions to prevent abuse and misuse. While we applaud western European countries for getting that balance right, let us not forget Kerala. In this tiny state right at the bottom of India, access to opioids is 16-times more than the national average. In the low-income Uganda, opioid access is three times better than what India claims. So, this shows it can be done. But why is it not happening universally? Is it because relieving pain or mitigating suffering is not a commercially attractive proposition for the industry that is at the heart of healthcare? Adding cost to suffering A study published by The Lancet on December 13, 2017, pointed at a vulgar disparity of life (to borrow Arundhati Roy’s expression). Not only are we not doing what we ought to be doing, but we are letting catastrophic healthcare expenditure add to the pain. The study aimed to estimate the global incidence of what they called catastrophic health spending. They measured this by the percentage of people whose out-of-pocket health expenditures were large relative to their household income or consumption. You are welcome to read the study for yourself. Personally, I was saddened and shocked to note that India was among the 12 countries burdened the most by the cost of health: more than 55 million Indians driven below the poverty line by what they had to spend on health; 38 million of them by cost of medicines alone. Such catastrophic health spending is not only for living with an illness; it is also for end of life—with the dying process excruciatingly stretched out over weeks or months in a desperate effort to prolong life at all costs. Are we afraid of death? Do we tend measure the “success” of medicine by how long it can keep death away? Is it difficult for us to accept that if life were a sentence, death is simply the full stop at the end of it? In January 2022, drawing on multidisciplinary perspectives from around the globe on the value of death, the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death argued that “death and life are bound together: without death there would be no life.” The Commission proposed a new vision for death and dying. It called for “greater community involvement alongside health and social care services, and increased bereavement support.” Cruelty of forcing to stay alive Moving away from professional studies and reports, let me narrate a personal experience. One of the professors who taught me medicine developed dementia. She was not swallowing well, so she was put on intravenous feed, against the advice of many of us. She would keep pulling the tube out. So, they tied her up. As every doctor knows, physical restraints can cause a 44-fold increase in the patient’s agitation. She did become more violent, and they promptly tied her up tighter. Eventually she was intubated and ventilated. The family had to walk in every morning and every evening for five minutes each, watching their beloved person being killed in order to be kept alive. Her daughter lamented, “Here was a person who gave a lot of love to a lot of people. Did she deserve to die this way?” Even as I write this, the daughter is receiving psychiatric treatment. I do not think she was affected so much by the loss of her mother as by the cruel way medicine kept her alive until the last excruciating moment. Why do our efficient, kind-hearted doctors refuse to accept that death is a part of life? Why do they hold on to the mistaken belief that it is their duty to prolong life at all costs? Is life merely a beating heart? The National Cancer Grid, a brilliant conglomerate of about 300 cancer institutions in the country launched the initiative Choosing Wisely India around 2020. The objective was to “identify low-value and/or potentially harmful practices in cancer care in India.” It intended to “facilitate a conversation between patients, clinicians, hospitals and policy makers on delivering high quality, affordable cancer care.” The aim was also “to reduce unnecessary interventions to improve overall quality of care, reduce patient toxicity and reduce the financial burden on both the patient and the system.” One of the recommendations was, “Do not treat patients with advanced metastatic cancer in ICU unless there is an acutely reversible event.” Laudable, isn’t it? But we all know what happens in hospitals. A friend, a senior neurologist, once remarked that our corporate hospitals are like fortresses that the poor cannot get into, and the rich cannot get out of. I do not think he was joking. A 2019 JAMA paper stated that in European intensive care units, 90% of all patients were taken off life support and offered palliative care once it was clear further treatment was futile. And, in comparison, what is the situation in India? Only 30% are taken off futile life support, that too any without palliative care support. As much as 70% of them die in ICUs. The end is stretched, hour by cruel hour for the patient, day by interminable day for the family. Helping us is up to all of us Let me get back to that woman and her son one more time. Yes, we treated her symptoms and pain. That was relatively easy but definitely not enough. One of us posted her story on social media and requested help. Help came. We now had money to pay for a caregiver while the patient underwent retinal surgery. After years, she got to see her son again. A diabetologist and podiatrist helped her get back on her feet, with support. She held her son’s hand and walked to a new home, where they are now supported by a monthly allowance, thanks to donations from the community. There is a huge gap between what healthcare is and what it ought to be. No doctor and no palliative care specialist can fill it by themselves. Does that mean we hide behind a definition and shut our eyes to the problem? The German physician Rudolf Virchow had said: “Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing but medicine on a large scale. The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them.” Our palliative care team is taking small steps. We are far from perfect, and it is a huge mountain to climb. But we are trying. By doing our best to support patients. By talking to the community about what we are doing and how they can help. There are many who want to help. But do not know how. Money is not the only way. I believe it is beginning to work. It has to. Right now, it is up to us to solve this social, or rather, humanitarian problem. Every World Palliative Care Day is a special occasion when those who can help get together with those who need help to celebrate life. One such day, in the city of Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala, some 40 people came to the beach to wet their feet. So, what was special about that? These were all people confined to wheelchairs who could barely move out of their homes. It took four people to move each of them from home to the beach and back. So, it took about 160 people to make this happen. All doctors and nurses? No! They were students from two engineering colleges.

And what was their reward? One of the patients was a paraplegic who did not have normal sensation in her feet. She said, “the waves touching my feet is the best experience I have had in my whole life.” She couldn’t stop smiling. That was their reward. And that is the reward for all of us when the community joins hands with palliative care and medicine to mitigate suffering in the true, complete sense. We have a long way to go. We have just wet our feet. There is a lizard on the other side of the pale curtain. It seems happy just holding on as the curtain sways.

The old clock ticks on, loud and relentless. The sound fills every gap in the banter and laughter. He is at the head of the dining table, most convenient to reach on his wheelchair. “Why don’t you make some tea?” he tells the maid. She is more than a maid. She was the chief help even when his wife was around. She took over as his prime caregiver after the wife’s death and an accident confined him to the wheelchair. A doctor who has come from a distant city checks him out. He obeys the gentle instructions. Raises his hands. Tentatively at first, grimacing at the pain. As the pain eases, a smile breaks through his white moustache and beard. As the testing and relieving continues, there is unceasing chatter, a lot of good-natured teasing between the patient and the doctor. The wheelchair handler is called in to understand the doctor’s instructions. Soak his legs in hot water before he goes to bed. As hot as, and as long as he can bear. As the doctor departs, so does the delivery guy from a grocer, who had been inside, stacking up stuff. The old man puts down his cup and resumes the story he was telling. Another trip down memory lane. Like the sun filtering through the leaves in a gentle breeze, dates and names are now bright, now in shadow. The maid signals the guests not to make him talk until he finishes the tea. Else he would again forget to sip. Again, she would have to reheat. He tells her to shut up and go away. She does just that. Keeping an eye on him but away from his eyes. She takes her time to respond and come to him when he calls her again. There is no malice. He is smiling. So is she, despite the sulk mask. No one who has interacted with him so far is related to him. Yet everyone around in the community is his family, tightly bound. By ownership, he ought to be alone in that grand old house. Someone or the other, from near and far, always ensures he is not. He is wheeled out, shouting out instructions for yet another get-together in the evening. The dogs waiting outside can barely contain their jumps and wags of glee. The clock ticks on as if urging the lizard to get a move on. It remains where it was. Tomorrow, more will come. So will more laughter. She chose hand surgery because she could perform that sitting, confined as she was to her wheelchair. The Sitting Surgeon would go on to give wings to many. Dr Mary Verghese was keen to study obstetrics and gynecology. An accident shattered her dreams and left her a paraplegic. After that she underwent multiple excruciating surgeries so that she could get better at being a surgeon, who could not stand. In Take My Hands Dorothy Clarke Wilson tells The Remarkable Story of Dr Mary Verghese of Vellore. Here are some extracts from the book that reveal what a struggle it was for Dr Mary to recover from two spinal surgeries. The [first] fusion operation was performed on March 14, 1955. Bone chips taken from her hip were inserted between five lumbar vertebrae, in order to effect rigidity. [After the surgery] body encased in two slabs of plaster, either one removable, Mary was again placed on a revolving bed. Twice each day she was turned. In the morning, the nurses would remove the top slab and bathe her. Then, turning her over, they would remove the other slab and bathe her back. For two or three hours she was left lying face down. The back slab was then replaced, and the bed turned to leave her again lying on her back. The procedure was repeated in the evening. It was for the hours of greater freedom twice a day, lying on her face, that Mary lived. Head taped and pillowed, a book lying on a low table below the open bed frame, arms resting on the table, she could read or study. Avidly she read book after book [including] volumes on the causes of nerve paralysis. Immobile, widening horizons Not that the longer periods on her back were wholly wasted. She used them to pray for other people and to strengthen her own spiritual life. She enjoyed the visits of her many friends. She shared the problems of students and nurses, listened eagerly to news of all the latest romances and even tried to promote a few. Friends brought flowers every day, and one doctor even fixed a pot of blossoms under her bed so she could see it when she was lying on her face. Dr. Rambo, the American eye specialist, brought a travel poster of the Jungfrau and fastened it to the wall. 'You need something to widen your horizons,' he told her with a smile. 'This will help.' It did. How it did! It stretched the walls to include unbelievable vistas. The pinnacle of whiteness was like a glimpse of heaven. Reflecting life around Nurse Effie Wallace, as ingenious as she was practical, had attached a mirror to a bar over Mary's head, reflecting not only her face but the trays of food set on her chest, so she could feed herself normally, with her fingers. Even better, the mirror could reflect objects outside the window: the big tree, a bougainvillea bush, people passing along the path towards the leprosy clinic. The second operation was for fusion of her lower thoracic vertebrae, utilizing bone chips taken this time from her leg. Back in her room, Mary began again the weeks of immobility and waiting: the imprisoning slabs of plaster; endless hours on her back; the two shorter periods of respite each day on her face, the open book on the low table beneath her, the pot of flowers a splash of brightness on the bare cement floor; the cheering visitors; the young nurses and student doctors dropping in for advice and gossip; the praying for the needs of others; the sounds of hurrying feet; the reflections of a tree, a garden, striding figures. [Some years later, the aircraft was ready to take off as Dr Mary returned after her Fellowship at the Institute of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, New York.] The doors were closed, the seat belts fastened. The great plane began to move clumsily towards the runway, like a bird out of its proper element … or like a human being intended to run on swift limbs but doomed to lumber on wheels. It came to a stop, shuddered as if in mortal agony, then with a roar burst its bonds, mounted upward into freedom. Mary felt a kindred surge of triumph. She saw far below a huge city shrunk to incredible smallness, a blue expanse dotted with toy ships, then nothing but sunlight and clouds and infinite skies. She closed her eyes in wondering gratitude. I asked for feet, she thought humbly, and I have been given wings. The Mary Varghese Institute of Rehabilitation is part of the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Department of the Christian Medical College Vellore. The Mary Verghese Trust that was started by her in 1986 continues to conduct vocational training programs for persons with physical disabilities. In recognition of her contributions to medicine, in particular, to the field of physical rehabilitation in India, Dr Mary Verghese was awarded the Padma Shri by the then President of India, Shri V.V. Giri in 1972. She died in December 1986 at Vellore. Portions extracted from Take My hands: The Remarkable Story of Dr. Mary Verghese of Vellore written by Dorothy Clarke Wilson. © Dorothy Clarke Wilson 1963.

Image of Dr Mary Verghese from https://givecmcv.org/rehab-mela/ Jungfrau Photo by Carol Jeng on Unsplash. These days there are so many World Days. Insert a word between World and Day and there! Not all those days matter to all. Except for some. Like today. Today, October 8, 2022, is World Hospice and Palliative Care Day. Palliative care is the branch of medicine that is about care beyond cure. It helps one live in pain-free comfort, with dignity, until death. And offers solace to the family that must live through the dying and beyond. That may make more sense if you or someone dear to you is suffering. Or is dying. When the only hope left is for some quality of life (some peace, no pain, sufficient comfort, dignity retained) until life breathes. Quality of life is something that matters to all of us in every stage of life. Most so in the last stage. I am fortunate to have two friends in professions that work to provide quality of life in different ways. Dr Priyadarshini Kulkarni is a palliative medicine specialist and the founder of Ease and Comfort. Lovaii Navlakhi is a certified financial planner and transitionist, and the founder of International Money Matters. What has money got to do with palliative care? Or with quality of life when you are in no position to earn? We will let them answer. Dr Priyadarshini Kulkarni “I know a family that has just two aging parents at home. They have multiple problems and are totally dependent on others for every little thing. They prefer to be at home. Among an array of people employed to help them is one person whose only job is to be with them and keep an eye on them. This person has no training as a caregiver. Yet, this help alone is costing them more than ₹50,000 every month. Imagine the total spend! How many families can afford that?” Lovaii Navlakhi “When we think money, we tend to focus on the quantity. The more we have, the happier we feel. I think what is more important is what your money is doing for you. Is the quantity of money you have giving you the quality of life you want? That is why responsible financial advisors first understand what you want to do in life, before working out the most prudent way to invest your money to help you reach those life goals.” Priya “Treatment of a major disease like cancer will drain a lot of money. As dementia progresses there will be an increasing need for constant care. It is not always about palliative or end-of-life care. As life expectancy lengthens, as more and more families turn nuclear, there is also an increasing need for independent, geriatric care. It is a long wait. That does not come cheap.” Lovaii “Insurance is important, but your health insurance policy may stop supporting you after a certain age. Your best bet when you grow old is your younger self, what your younger self wisely put away all those years ago.” Priya "In most cases, the role of palliative care is to ease pain and provide comfort. But what often hurts the most is the loss of dignity. There was a very successful entrepreneur, who was once the king of his domain. He was now helpless, terminal. He wanted to know if it was possible for me to speed up the end. What was unbearable for him was to have his wife and daughter-in-law, the only family he had at home, take complete care of him as he just lay there. He did not want to be at the mercy of others. The problem was solved by handing over all care to medical professionals. Fortunately, the family could afford that. How many of us can?” Lovaii “Parents are so eager to educate their children, get them married and set up a home for them that they start saving right from the time their child a born. What they forget is to provide for themselves. By the time they realize that, it is too late because the cost of care is always rising. They end up being what they never wanted to be—a burden on their children.” Quality of life can mean different things to different people. Even for the same person, it can mean different things at different times as life goes through its inevitable phases and transitions. We do not want to talk of death. Nor are we comfortable talking about money with family. We cannot escape either, death or money. Between the two, why not plan the reality that we have more control over—money? Palliative care helps you live as well as possible until you die. And it preserves dignity by respecting one’s life till the end. Financial planning can facilitate this, for oneself and for others. Maybe it is time for a couple of name changes. Let’s change financial planning to life quality planning. And let us celebrate today as World Quality of Life Day. |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed