|

Executive search firms are warning that companies persisting with a five-day work week may have to do with “leftover talent” as candidates may refuse to join or leave soon after. Do we blame that virus again for this? Have all of us been spoilt by the commute-free experience of working from home? When the WFH-WFO debate first hit the headlines, the virus villain was not part of the vocabulary at all. Instead, it was Marissa Mayer, the then new CEO of Yahoo who had garnered all the hits for abolishing the company’s work-at-home policy and ordering everyone to get back to the office. Then, as now, what the headlines have missed is that I have been at home and productively working for more than a quarter century. Then, as now, what really matters is not your location but if you feel at home where you work. Home, work homeIn my early days, entrepreneurship was a euphemism for glorious, uncertain, nail-biting unemployment. I would often land up in the office (he had one!) of a friend. I would pretend to have just come from a client meeting; he would pretend to be rushing off to another. After both of us got comfortable enough to shed our masks, the first question he asked was, “How do you manage to stay awake at home? I could never bring myself to leave the bed. That is why I splurged on this *&%#$ office.” A young manager once sat me down to have a chat. When I told him I was not a management graduate, he looked at me as if I had just crawled out of the coffee vending machine. Just to make him comfortable, I assured him I came to office only two days a week, that too for a few hours. “It is just not professional,” he burst out. My job of writing used to place me in offices full of interesting people for several hours a week. They are rarely so accommodating today. But I am fortunate to be still working with some very intelligent people (some of them are so good they reject my work and then offer tea to make me feel better). I must understand all dimensions of an issue before I can attempt to resolve it for my client through my writing. That conversation used to happen in the office or, more commonly, in the conference room. Now, we meet on the monitor. As for the actual writing, I have always done it at home. Which means I have always spent more hours at home than in various offices. Which makes the housemaid throw deadly looks at the leech shamelessly living off his poor wife, who must trudge to work every day to keep the family alive and pay the servant’s salary. Innovatively productiveJohn Sullivan thinks I have the mix right. That old New York Times report about the Yahoo missive quotes this professor of management at San Francisco State University, who runs a human resource advisory firm. “If you want innovation, then you need interaction,” he said. “If you want productivity, then you want people working from home.” Now you know what I mean when I insist I am “innovatively productive”. Susan Cain writes in her book Quiet what collaboration meant for Steve Wozniak, the co-creator of Apple: “The ability to share a donut and a brainwave with his laid-back, nonjudgmental, poorly dressed colleagues—who minded not a whit when he disappeared into his cubicle to get the real work done.” No client has yet shared a donut with me. They have been generous with the brainwaves, though. I lug it all and disappear into my cubicle—my home. In the same book, Susan Cain talks about Pixar Animation Studios, where “the sixteen-acre campus is built around a football-field-sized atrium housing mailboxes, a cafeteria, and even bathrooms. The idea is to encourage as many casual, chance encounters as possible. At the same time, employees are encouraged to make their individual offices, cubicles, desks, and work areas their own and to decorate them as they wish.” So, it is about creating little spaces where you feel “at home” in the office. That is exactly what I have been saying. You need a prudent mix of efficient home and homely office for optimum productivity. Be anywhere, but work I recently shared this idea with an entrepreneur, making it sound as if I had thought about it all by myself, well before time, even before the virus.

This company was among the many hit hard by work-from-home while their customers all seemed to have gone home. When the skies cleared a bit, they experimented with a smiling come-to-work-when-you-can, later switching to a growling you-better-show-up-or-else. They went on to lose a bunch of people. Now they use work-from-anywhere-but-please-work-for-us as their prime recruitment strategy. That reminds me. I have to prepare a presentation for them. I will start on that as soon as I finish chopping the vegetables. Ever since my wife restarted going to work, our maid has adopted a may-come-may-work strategy.

4 Comments

Before she could reach the toilet, Dadi soiled herself. With great difficulty, ignoring her protesting joints and constant fear of falling, she cleaned it up. She did not want to wait for her servant to discover the mess she had made. Her servant scolded her loudly, especially when Dadi's son was not at home. She did not want her servant to abandon her. Dadi was so dependent on her servant for everything. In Rani’s case, she was the servant, and she was the one who had been abandoned. Dadi's news reminded me of Rani's story that I had heard some years ago. Rani was 11 or 12 when an earthquake destroyed her home and family in a small town in north India. One year later, after he collected the earthquake relief money from the government, her uncle, the only other survivor, kicked her out. Rani landed in Mumbai, where the people of the big city and their ways made her uncomfortable. Finally, she reached Pune and found employment with a family. She became the full-time caretaker to the old woman of the house. They forged an affectionate bond. The old woman promised Rani better days and a better living. Rani’s prime years passed her by as she lived for her dreams. Many years later, the old woman died. And Rani was back on the streets. From street to destituteShe found a job at a school. After some years, she started working at the home of the head of the school. When her bleeding and the pain in the abdomen did not ease, her employer took her to a government hospital. The diagnosis: cancer of the cervix, malignant and very advanced. Her employer then brought her to what Rani thought was another hospital. At the time of admission, she reassured her employer, “I will come back and work as soon as I get better.” Her employer snapped back, “I never want you to come back.” The palliative care centre admitted Rani as a destitute. Finally, living her lifeAs the pain subsided and she started feeling better, Rani did not know how to deal with the attention she was getting. The nurse often found her sleeping on the floor at night. “The bed makes me feel like a queen. I am more comfortable here.” Now that she had a new family, Rani suddenly became a child and started making fancy demands. Vada pav, puri bhaji, lassi and Coca Cola were among her favourites. “And please don’t get those from the canteen, buy it from outside.” The raging cancer would not let her keep anything down. One bite and she would throw up. One sip, and she would apologetically close the bottle and keep it away, to try again later. “No more fancy food; just eat what we give you,” the nurse said in mock anger. Rani laughed; the nurse helplessly joined in. The attendant gave her a bath, combed her sparse hair, and tied it into a thin bun. The security guard came with a flower. Would it look nice on her hair? One night, Rani died peacefully. She was 70. Gone, troubling noneThe employer sounded relieved on hearing of the death and reaffirmed that the institution was free to do what they thought fit. The institution had a signed document that authorized them to do what they felt right with the destitute before and after her death. The police had endorsed the document. The crematorium got a copy of the document too, along with the death certificate and a copy of the driver’s license of the person who took the body there. They all took care to make sure they would not be in trouble later. As for Rani, after some 50 years of serving others and 20 days of living for herself, she did not care anymore. Rani was not her real name. And very few know Dadi's name. Everything else above is the truth. For Rani then as for Dadi now, every day that they do not cause trouble for others and get scolded, is precious. Those are the days they experience a little love and dignity and forget they are no longer useful to others.

“Have you even had sex yet?” my professor asked me, shocking me into silence. There was a sudden hush around us. We were at a café just below the bank where I worked. And in that office, that very morning, my boss had advised me to reconsider my decision to quit. “You must remain constantly bored and frustrated. Only then will you do very well at your hobby. You need to keep this job to be a better writer.” The professor had surprised me by dropping in “just to see you busy at work.” He looked amused as he watched me busily stamping countless documents, stapling the papers the typist passed on to me and fetching files. My boss kindly gave me permission to step out of the office to have coffee with the professor. “But don’t take too long. People may need files.” The professor was the one who had discovered the writer in me during my final year in college. And he took the trouble to stay in touch after I graduated, reading and commenting on every masterpiece (so I thought) I wrote and snail-mailed him. We had barely sat at a table when he pulled out a familiar looking piece of paper from his bag. It was the poem I had sent him last. I was secretly proud of that scathing commentary on the state of the nation, with lines like “blood of our rapes flowing on the streets.” That was precisely the line he had read out before asking the question that had silenced all conversations in the vicinity: “Have you even had sex yet? And you write of rape and blood.” "Write about what you have experienced," he advised. “I am not asking you to go around raping and murdering. Write from within. You have the potential to be a writer. That does not mean you can pass judgement sitting on a pedestal. Experience life. Meet people. I am glad you are leaving the bank. Don’t give up writing. Write honest.” I have forgotten whether we had tea or coffee. But that meeting came back in painful detail when I recently read the warning, “turning play into work can really dull the joy.” Should I have listened to my bank boss 40 years ago? Hobby's journey to jobA course in journalism and a stint in a newspaper told me that being a writer was not the same as being a journalist. In fact, the day I joined after chucking my bank job, the Chief Reporter put a fatherly hand across my shoulder and said, “You look like an intelligent boy. How could you make this mistake?” Then came the job in corporate communications. It was a wonderful opportunity to talk to everyone from the worker to the director for the newsletter. Everyone applauded every issue, my creation! Except my boss. Until the day he exploded when I got someone’s name wrong and discovered it after the issue was printed. “You think you are a great writer? Hah! You can’t even get the basics right!” The writer took two steps back; the employee responsible for carefully and correctly projecting the company’s image stepped up. The tie was the memorable aspect of the job that followed—with a PR agency. I do not remember doing much beyond scanning newspapers, sending clippings to clients and writing endless press notes. It was a struggle to knot the tie correctly in the cab on my way to the next client meeting, especially when it was a short ride. I got rid of that tie and left the job soon. I felt very brave and liberated when I decided to be an independent writer. It didn’t take long to miss the regular salary flow. God! When did everything get so expensive! “You mean to say you sit at home, write and people pay you?” my mother asked. “Why don’t you admit you don’t have a job? Your father is not there now, and you have your own family to look after,” she sighed. She was probably wondering where she had gone wrong in my upbringing. “My father was doubtful if an editor would be able to support me, when I chose you,” my wife confessed. It didn’t help that my first son had already started school and another child was on the way when my wife decided to pluck that material memory from yonder. Many hats, same headThe tie went away for good but I did end up wearing many hats—copywriter, scriptwriter, medical writer, technical writer, web writer, storyteller, coach. Until I was commoditized as a content writer more recently. Were there any lessons that could be bulletized on LinkedIn? Maybe it started with my professor, but the lessons have not stopped coming. “Your sentences are long. Very boring.” “You write very abruptly. Too many short sentences. Almost impolite.” “Why do you use such simple words? You are writing the Chairman's blog." “Can you use this word in the headline? I like this word!” “Very moving script about the farmers. Now, get moving and change it fast. Put in some charts and figures. We need this to get funding. Not win an Oscar.” “You write so easily and effortlessly. Why do you want to charge for it? After all, you said you enjoy it, didn’t you?” Want to vs. need toCarys Chan, research fellow at Griffith University’s Centre for Work, Organization and Wellbeing, quoted in this article warns that monetizing one’s passion project can jeopardize its appeal, but “if the gap between your passion and what you’re actually good at is small, or they are aligned, that can obviously be a great outcome.”

That sounds very wise. The simpler formula I have learnt to apply is to enjoy what I write for myself. And I equally enjoy what you want me to write your way, provided you pay. I am sitting in front of a potential client. We are in the office of a common friend who had brought us together. He has just finished running through a crowded Excel sheet that began from all the products he was planning to launch within the next year and went on to list all the social media posts he wanted on multiple platforms within the next two weeks. It is obvious he has been tutored by others as to what he was expected to do. I let him finish. Then I gently helped him close his laptop and pushed his waiting tea towards him. While I took a pull at mine, I asked him where he was from and about his family. My questions were in a language both of us were more comfortable in. He sat back, let out a breath, reached for his cup, took a sip and smiled. “I am a farmer,” he said. I love my job. By the time the noise woke me up early that morning and I rushed down, it must have taken them some eight chops to cut the big branch that was obstructing the hoarding.

It took them only two from the same axe to severe my neck as I ran in screaming to stop them. When I came to, I was being cradled by someone, something soft. I felt strangely weightless. Then I saw I was on that tree, and I was being cradled by that very tree. I wanted to scream and struggle but somehow felt very peaceful. “Don’t worry, you will get used to it. You are no longer that,” the tree said pointing to my body below. “You are back to being your essence now, just as I am.” That’s when I noticed the rest of what was the tree lying in pieces around what was me. You saved me? I asked in confusion. “Well, I have been carrying you for a long, long time. Maybe saving you also. Long before you made that axe and started using money. Now you just use the axe on whoever and whatever comes in the way of your making more money. Just as it happened to you.” Are you God? “We all are. You just forgot along the way. Now it is easier to use God when it is convenient, especially to make more money. Even use the axe for that.” Can’t you punish them? “Why should I? We are all heading for that final punishment that will offer no escape. Axe or no axe.” But why me? I am the good one. I help others. They killed me because I tried to save you. “There is no you and them. You are all in it together. You live together or you die together. Not long now.” Maybe you should make me alive again. I can write about them. Expose them. The story will go viral. I felt something like a hand gently moving over my head, over my eyes. “Rest now, child. You will see something. You may write as you are so keen. Then you will forget everything and be born again.” The last thing I saw was the hoarding. It was to celebrate World Environment Day. It showed more faces of leaders than saplings. One of the faces looked vaguely familiar. Had I seen that with the axe? A child was born to the Shirpurkars in November 2000. It was a joyous occasion for family and friends. Then came the time for the child to toddle around. Something was wrong, the parents thought. He was falling more than walking. He struggled to maintain his balance. Soon came the diagnosis. He had a rare genetic disorder: Duchenne muscular dystrophy. His muscles would continue to waste away. There is no cure. It was not easy to find a school that would accept him and his companion disabilities. “Inclusion must start in school. Else, discrimination will persist. My teachers played the most important role in my life, preparing me for all that I have ever done and will do in my life.” He would go on to graduate in Economics. “I wanted to do Engineering, if only to prove a point to those who tried to dissuade me, given my condition. Then I thought about it and chose my favourite social science—Economics.” He was a brand ambassador for the first Wheelchair Accessible Beach Festival in India in 2017. He is associated with an NGO working for inclusion of disabled individuals. He has been a blogger right from the age of 13. “I enjoyed writing while in school. My early efforts were rather immature. But I kept at it as a hobby. In college, English was a compulsory subject, including blog writing. That led to my current blog.” And at 22, Dhruv Shirpurkar has just published his first book, Solace. “After I managed to finish my graduation, blogging became a full-time profession. Wrote more. Readership improved. Gave me confidence. Why not write a book? Publishers and agents were taking too long. Given my health condition, it was wise not to delay. Another bout of pneumonia and anything could happen. So, I went ahead and self-published my dream project, this book.” We matterThis book is a collection of the random thoughts of a young writer who is disabled in body, not in mind. His thoughts force all of us to think. In his introduction to the book, Dhruv makes it clear that the book is not his biography. “I have not done anything extraordinary in my life, but it is more of a book that is meant to help others.” Until recently, he was quite bothered that he had not done anything extraordinary. He suspects many of his readers might have the same concern. This is what he wants to tell them: “It doesn’t really matter what we have done and what we have not done in life. We all have some role to play in God’s divine plan whether we know it or not, whether we believe it or not. We are all worthy and we matter.” My disability is not my identity

Inclusion must start in schoolDhruv remembers looking for a school as a painful phase for him and his parents. Many schools were unequipped for a student like him. Many were unwilling. After a long and frustrating search, Nalanda Public School accepted him. “Thankfully my school was very inclusive.” He narrates a school incident in the book. He had gone to the washroom (with his attendant). His classmates were making a lot of noise. The teacher punished them by making them hold their ears. When Dhruv returned, he was excused from the punishment as he was not present. Later, his angry classmates passed some insensitive comments. “If this is the privilege he gets, then even we will also come on a wheelchair and pretend to be disabled, so that we will be excused,” someone said. Dhruv angrily responded, which worsened the situation. Then, one of Dhruv’s favourite teachers stepped in. She made everyone understand that they were all classmates with inherent differences that all should accept. She went on to encourage everyone to speak up about their grievances, just to clear the air. “My teachers have really taught me what it is to love someone unconditionally even though that person may not be related to you. If you cannot love your fellow human beings, then you have achieved nothing in life. This is what made my schooling the most extraordinary experience of my life. It truly makes me feel that I did not just go to a school of education, I went to a school of life.” It is positive to let goIt is not easy for many, especially the members of a disabled person’s family to accept that the problem cannot be resolved. Yet, in hope and in desperation, they keep trying, even resorting to “pseudoscience”. In his book, Dhruv suggests that leaving hope is not bad. “Sometimes you have to stop hoping for something better and start living. Leaving hope is not bad if it allows you to take control of your life. It allows you to bring change. It guarantees success, something hope won't. You underestimate yourself thinking change will come. You are the source of change, and everything is in you. A change will come only if you work towards it. Otherwise, you are hoping for a miracle and miracles are not miracles if they are expected. Positive attitude involves letting go when you know there is no point hoping. So, stop hoping and start living.” The idea of deathWhat does he think of death? Dhruv is calm and clear when he shares his thoughts during a conversation. His idea of death is simple. “We accept death for others, not for ourselves and not for others without whom we cannot live." His medical condition forced him to ponder about death right from puberty. “Unlike what was expected out of me, I did not develop negative emotions about it. Instead, I came to the conclusion that there is no point struggling with it. I decided to accept it and forget about it. Not about the event itself, but about its consequences.” Is he comfortable talking about death? “Yes. But I am conscious of speaking about it because of the way people respond to it. This response is dictated by their belief that I have certain negative emotions attached with it and I have not accepted it.” He compares dying to growing. “One doesn’t know while growing what good will come of it until he experiences it. I also do not know what good will come out of it. A child plans what he or she is going to do in life with the conviction that nothing is going to deter him or her from achieving those goals. However, the child cannot see the future. This is how I like to think about death.” Solace has moreSolace has more to make the reader think and smile. Like the personality sketch of a cool cat. The reason why the microwave went on strike. Then there are some interesting poems. There are also some profound thoughts on spirituality. The book may or may not occupy the pride of place on your bookshelf. But you will want to keep it within reach so that you can connect to Dhruv whenever life throws a seemingly insurmountable obstacle at you. His approach and words might help you overcome and move on. Dhruv wants his readers to “hold on, continue on your journey and don’t listen to anyone else when your heart calls out to you.” A website had run Dhruv’s story under the headline, “Don't look at him with pity; look up to him for his grit.” If this book makes you shun sympathy and embrace resolve without fearing failure, Dhruv would have succeeded in his mission to help you succeed. After all, he wrote this book for you. To buy your copy of the book, please write to Dhruv at dhruvshirpurkar@gmail.com.

Image credits: Dhruv Shirpurkar; Rediff.com; Mid-day.com I would like the time of my dying to be a time of celebration. I would like my caring team to make me as comfortable as possible, so that I can spend the remaining time the way I want to. I hope my family will accompany me on the path that I choose, and not drag me along in the direction that they decide on, even if they think there are certain miraculous solutions to be found there. Respect life, respect deathI hope the custodians and practitioners of the science I have learned—the noble medical science—will be compassionate and remember that there is an art to healing as well. I hope they will not succumb to some inner Frankenstein, programmed to believe that they are obliged to keep my heart beating, or that a beating heart is more valuable than a soulless existence; greater than the cost it inflicts on me and my loved ones. I fervently wish that I am not imprisoned in a cold intensive care room, isolated from my family when I need them most. I hope my fellow health professionals will permit themselves to recognize that just as they have a duty to cure my disease, if possible, they must also accept incurability when inevitable. And that just as they respect life, they need to respect death too. Incurable, still humanNo therapeutic scan has yet been created that can measure happiness. There is no medical intervention yet that can generate joy, but the love that I give and the love I may receive. If I am made physically comfortable within reasonable limits, this love could well be the only thing that matters as death approaches. I believe I have a right to a compassionate and responsive medical system that will not reject the human being in me simply because my disease is incurable. I hope I am not force-fed if I am no longer hungry; I hope my doctor will not fear administering a sedative, if I indicate that I want to sleep. I hope that if I reach out, my hand will be met with a friendly grasp in the darkness. And, to everyone, who has given me abundant love, my family and friends; those who arrived as patients and their families and became fellow-travellers, teachers and partners; my many colleagues past and present—there must have been so many ways in which I could have treated you better. I hope you will not find it too difficult to forgive me my faults and weaknesses. If you can think of a few good moments that you and I shared, my life has been worth living. The above abstract is from the book Walk with the weary: Lessons in humanity in health care written by Dr. M.R.Rajagopal. Yes, he is one, but it would be irreverent to call Dr. M.R.Rajagopal just a doctor. He has held the hands of many as they walked the tortuous line between life and death. He has eased pain, wiped tears, restored dignity and more. And he continues to teach many to do all of that. All of us need to read Walk with the weary. Because all of us are going to die one day. Because all of us deserve to live as we would like to until that last moment.

You learn the best when your device loses power. That’s when you drop down from your wish-world to hear the music of life around you. Ugyen the young teacher in Bhutan was dreaming of escaping to Australia. Then he was posted at the most remote school in the world in Lunana, a tiny village nestled among the clouds. He had come to teach rather reluctantly, but he kept learning as his device waited for solar powered resurrection. He learnt the value of all that was around him. Like that of a piece of dried yak dung when you need warmth and food. In what passes for the classroom, A can be for Apple and B for Ball, but C cannot be Car. Because no one knows here what a car is. It must make way for a Cow. The aspiring musician, used to applause in the bars, learnt that a song is an offering to all beings and spirits. And that one must sing like the black-necked cranes. They are not concerned with who is listening. See Lunana: A Yak in the ClassroomThis film is the directorial debut of Pawo Choyning Dorji, the Indian-born Bhutanese filmmaker and photographer. Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom was nominated for the Best International Feature Film at the 94th Academy Awards (where a slap during the presentation won all the headlines).

Bhutan is a country that measures its economic and moral development in terms of gross national happiness. As an integral part of this, education is a must in every remote corner of the country. No wonder, the entire 56 people of Lunana walked two hours to welcome the teacher, who they hoped, as the village chief put it, “will give these children the education they need to become more than yak herders and cordyceps gatherers.” A herder teaches Ugyen a folk song that celebrates the sacred bond between herders and their yaks. Later, far away in teeming Australia, as the indifferent patrons of the bar where he croons for money ignore his rendering of a popular number, he stops singing. Then, from his heart, rises that folk song. It was his offering to himself. Even if you are not into lessons, watch this film for the breath-taking views and its sheer simplicity. Or to simply tune into what is around you. The new C is in the spotlight. The old C remains. There is no masking the fears about cancer. And there is no distancing the misconceptions.

Chanda. The name of the girl is not. But the snatches of conversation, more about her cancer than her, are all real. Father to doctor: “She keeps getting fever and is so weak.” Doctor to father: “Your child has blood cancer. We will have to start chemotherapy.” Mother to father: “But she is only five. How can she have cancer?” Chanda to mother: “Did you fight with Papa again? Don’t cry, I am there for you.” Father to mother: “Never again will we cry in front of her.” Father to mother: “I have no money left. Don’t know whom to ask. Let’s release an appeal.” Stranger to parents: “Saw your appeal. Oh, she likes cars! Come, bring her, let us go for a ride. Keep this money. Why does it matter who I am?” Mother to school principal: “Doctor said she is recovering and can start school. Please admit her.” Principal of school 1: “If other parents come to know, they will withdraw their children. As it is, we are constantly fighting with parents.” School 2: “What if her cancer spreads? Other children will also get it.” School 3: “We can’t let her skip class every time she has to go for treatment. What is the guarantee she won’t get it again?” School 4: “She must always wear a mask, sit separately and not mingle with other children.” Mother’s letter to father: “I am going. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life looking after a cancer patient.” Chanda to father: “Why are you crying? I am there for you.” It was a hot day, with the tin roof adding to the heat inside. The children in the class were eagerly reciting a poem when the tinkling of a bell drew my eyes to the window. It was a buffalo, followed by its minder, a girl of the same age as the ones heartily singing for my benefit. Some of the students waved out to her as she paused for a moment near the door. She should have been in the class too; just that she had to swap her books for the buffalo … one of those days. I was a guest, a rare visitor from another world, far away. A world many of them can’t see, not even on television, because you need electricity for TV. They assumed I was there to “judge” them and they were determined to put in their best, complete with safety pins to hold up torn skirts and trousers. Plastic chairs walked in on human legs, as small boys staggered under the weight of the chairs for the visitors. Two girls, who seemed to have forgotten to smile, worked the hand pump to draw water for tea. They entered the headmaster’s room with trepidation, carrying cups filled to the chipped brim. The teachers told me they were happy to have one boy back in class. He had gone missing for months, accompanying his parents as they travelled, yet again, to another district for sugarcane cutting. He was smart; at least on the days he was present. It was chaotic to have two classes sharing the same room. But that was progress after years of learning in a teacher’s home, jostling for space with goats and cows. The teachers did not complain about having to walk 2 to 5 kilometers every day as they divided time between schools. Jobs are not easy to come by, especially when you are handicapped by education. The students did not complain about the irony of learning good deeds and good words when a drunken father beat them up at home and the mother thought nothing of unleashing a curse every time she called out to them to handle another chore. As I walked out, carrying the precious coconuts and shawls they had gifted, I cringed at the memory of the pride I had felt just the previous day. A corporate king had praised my presentation that painted a rosy picture of the services he was rendering to society. I had just woken up to the real world and smelt honest earth. They had served me endless cups of sweet tea and tall glasses of sugarcane at every village. Yet, something sad and bitter lingered, somewhere deep within. My friend, who has chosen social development as his career (his specialty: taking science to remote schools) is not surprised at what I had witnessed 10 years ago. He is not stationed at the village that I had visited but assures me things have changed.

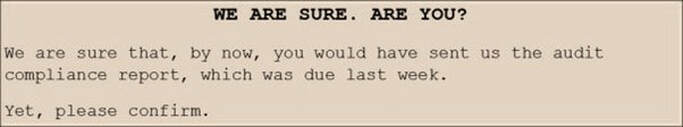

“Parents now realize the value of education. They make it a point to ensure that the children go to school.” We have the virus to thank for it, he says. All those days the children were forced to stay at home, parents learnt the important role of teachers in education. “They were just not able to cope, even those who had a mobile phone. They realized that only education could give the children a future. And they cannot educate. They needed teachers as much as the children.” For my friend and his team, it was a challenge to bring the teachers up to speed in the ways of the virtual. “They were fantastic. So much so that the first group we trained became role models for the government.” Then there was the challenge of educating those children whose reality stood no chance of catching up with the virtual. “We prepared special books for them with plenty of pictures. One day, when they all go back to their real classrooms, we want all of them to be at the same learning level.” Now that the children are back in the classroom, the teachers are facing a different challenge. “The children are distracted. It is a task to make them sit in one place and pay attention.” Even for the best teacher, it is difficult to match the addictive entertainment value of a smartphone. My friend cautions me that this is a work in progress. And he does not yet have the all-important data. Nevertheless, he is optimistic. There is at least one sugar mill that now ensures that the children of the laborers working in the sugarcane fields can continue their education uninterrupted. The buffalo has not gone away. Hopefully, its virtual avatar now shares the class with the girl, instead of leading her away at the end of a rope. All of us like surprises, at least the pleasant kind. Even when lit up screens have pushed printed pages to the background, you can delight your reader if you add a bit of wit to what you write. More so in the heading. “Mosquitoes ‘play’ menace at Bal Gandharva, people ‘clap loudly’... to kill them!” screamed a headline just this morning. Bal Gandharva is a popular auditorium in the city where I live. “Instead of artistes, the mosquitoes had taken centre stage,” the report went on to say. When a famous cricketer passed away recently, wordsmiths gave it a real tweak: “He took us for a spin, left without a Warne-ing.” Of course, when you have been a famous cricketer, the pitch condition can disturb your stance even when you are alive: “Imran Khan c Constitution b Supreme Court of Pakistan.” Technical glitches can get unappetizing for food delivery apps, especially when the media add a dash of spice: “Hungry users fume as Swiggy, Zomato take a ‘lunch break’.” NSFWHowever, witless use of words can backfire. When a decomposed limb was found in a playground, and the police had no clue, a tabloid boldly announced: “LEG STUMPED”. While the play on stump was, perhaps, not lost on the readers, many found it insensitive, even morbid. Yes, a little twist can get attention. But your readers must immediately grasp the context. They must not only spot but also appreciate the play on words. If there is even a whiff of controversy, it can raise hackles. The ensuing debate may overshadow the substance of your message. Which makes it a tricky tool to use in the office, definitely not safe for work. In the head office of the bank, where I used to work a long time ago, it was routine to send reminder letters to branches. It was my job to prepare the template, change the number of the reminder (REMINDER No. 5) and submit it to the officer for signature. Nothing ever changed except the number. Not that it mattered to the recipient who hardly bothered to respond, even if the number reached double digits. A young new officer took charge and decided to freshen up things. And I was happy to be his partner in crime. This is the reminder he sent, probably the shortest in the bank’s history. Within days there was some very officious uproar about the breach of “protocol” and violation of the bank’s “style of correspondence.” I do not remember if that reminder managed to get the report it was seeking. But, for a long time, even a little note from that officer got immediate attention from everyone. His boss pleaded with him to use “normal English.” And they transferred me.

Yes, go ahead and give it a twist if it gives you a kick. But make sure all will get it, and none will be upset. Else, you will end up with snubbed toe. |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed