|

How to write right? I put that question to her. She is a wiser, older writer, who never misses an opportunity to tell me between the two of us she is always “righter”. “In what you do, what is right writing is what your client says is right,” she banged her fist on her palm, as was her habit if there was no table within reach. As Messrs. Wren, Martin and Roget had played a major role in shaping two of my three R’s, it was not easy to accept her assertion. Yet, she did have a point. Long ago, when covid would have probably been highlighted as a spelling mistake, I was surprised by a call from Hong Kong. That was my first overseas client happy to have me WFH (another spelling glitch then). We worked happily for about two years. One day, he abruptly told me the boss was not happy with my writing. “Too direct, almost impolite.” Soon, they moved on and he (now a friend working elsewhere) revealed that the boss had changed—the American was replaced by someone from the UK. Was it just a matter of the difference in nationality? Could we have solved it simply by UK-ing US English? Apparently, there was a change in temperament too. Conclusion: You may spend hours sharpening it, but a change in nationality and personality can snap the lead, just like that! Now I am quite used to both extremes. “Your writing is too simple. Can we have some strong words?” “Your writing is too complex. Please simplify.” I simply comply. When writing is your work, write what works. A new book, Writing for Busy Readers, reviews The Economist, has very simple advice: cut unnecessary words, stick to “bedrock vocabulary” and follow simple syntax. The book goes on to give proof of the preaching. Simply deleting half of the paragraphs in a fundraising email increased donations by 16%. Reducing the words from 127 to 49 in an emailed survey increased the response rate from 2.7% to 4.8%. Public companies that used long sentences and complicated words to state their ethics code were seen as less moral and trustworthy. Phew! Short and sweet it has to be then? What happens when the first-level contact at the client’s throws your content on the scale to weigh the “content”? How many are fortunate enough to deal directly with the would-be author to understand them and their authentic tone well enough to make the draft a “good to go” at the very first instance? Of course, without interference from chatty intermediaries and GPT! Short, easy words definitely have their place but not for all. This “sesquipedalian” Member of Parliament (MP) is known less for what he says than for the words he uses to say that, whether you understand or not be damned. That’s his brand, what has made him famous. An old friend, an ageless writer and veteran communications professional, had the opportunity to compliment this MP after the latter had addressed a gathering. “Thank you for elevating this discussion to crepuscular altitude and suffusing it with intellect of refulgent luminosity.” Incidentally, this friend’s first book will be published soon. When he told me about it, I suggested he should title it Condiment-laden Camellia sinensis decoction for the neshama. He refused. Must be the influence of the new wave. He has given it a title all too simple and short: Masala chai for the soul.

6 Comments

In my early days as a writer for hire, the lack of a degree in literature used to push their eyebrows up and my chances down. As the decades passed, another missing qualification emerged to replace the academic shortcoming—haven’t written a book yet, have you? I may have encouraged or helped many write a tome, but the fact remains there is no book out there in my name, neither the version that evokes bibliosmia nor the one that stays behind a screen until clicked to life. Friends persuade. You have written so much, why not put it all together in a book or two? Flattering as it is, I share a secret: it’s all out there already in bits and pieces. Why go through the pain and pay a price for booking it all? That’s when they give up, accusing me of laziness, arrogance, and hypocrisy! Does he know anything about building a brand? Says he is a writer, but doesn’t want to write a book, bah! Maybe I am being a hypocrite when I encourage and help those clients (and friendly ex-clients) to write the book that is bursting out of their heads and hearts. But at least once I actively discouraged someone. The draft of his blog had ended up being a bit too long. Within hours he was planning the events and locations where he would display his first book. I doused his enthusiasm by ruthlessly editing the piece and converting it into three posts. You guessed it, he is no longer a client. Though he does remind me on the rare occasions we connect that together the three posts had garnered some 5,000 likes. No doubt suggesting that the book would have sold an equal number of copies, if only …. By the way, Mark Richards of Swift Press, says in The Economist, that 5,000 copies is the break-even point for a book. That is the number a writer should target to reach base camp from where one can hope to glimpse the best-seller peak. Anyone can book now Time was when you would be rejected by publisher after publisher. I used to imagine a whole lineup of serious-looking editors trying to inject English into the manuscript (after clearance by the marketing team). Can you write good, readable English? Can you sustain a plot? Are you relevant, famous, or both? Will they pay a price to read what you write? Every question needed a positive answer, before the book could see daylight. Or so I used to think. Now, as Abhi Singh puts it, there are no gatekeepers. You are not screened and selected by a publishing house. A lot of us have always wanted to be an author even when it was not easy. Now that publishing a book is as simple as going to the right website and clicking on the best package, there is a rush to stuff your words between the covers and put it out there. In the past, says Abhi Singh, “publishing one paper book would cost so much you would have no money left for sending out a new one. Now it’s just bits in the ether and cost nothing.” Talk of publishing e-ase! Today, publishing a book is all about branding. If your head is chockfull of ideas and you just need a plumber (ahem!) to get the words flowing, you can hire one and also all other sorts of help (if your publisher does not offer those). You may not even need to step out of your room (where you have your computer) until it is time to launch your book and sign a few copies. And once that is done, never miss an opportunity to suggest that you are an author, which if you do it right often enough, would become synonymous with “I am an expert”. A book matters, but ... Before you rush to the conclusion that I am anti-book, let me correct you. As long as you are clear about the why and what of your book, I will be the first to cheer you. Imagine you surprise me with a copy of your first book. Days pass after all the congratulatory backslapping. As promised, I get back to you after I read the book. The silence gets awkward when I ask a simple question, purely as your reader-friend: “Why did you write this book?” I have had to painfully put up with that silence more than once. What makes things worse are the justifications that follow and the accusations of my being disloyal and needlessly skeptical. Then there is this friend who has occupied the top echelons of management in places that normally figure in the shadow regions of newspaper headlines. You may ignore his management wisdom but there is no ignoring the weight of the life he has experienced in difficult situations. He remains a consultant not to fill his coffers but to fund a foundation that supports budding entrepreneurs. “I want to write my autobiography. No grand book. Just to pen my experiences in some form, somewhere. I want my family and friends to gain from what I have learnt. I have nothing to preach, but a lot to share. Hopefully, that will help someone, sometimes. Just to discover their answers within themselves.” In his case, the target is not fame or brand building. You will hardly spot him on social media. His book, whatever form it takes may not make it anywhere near the bestseller list. Yet, he has a good cause for writing the book. Which gives it a good chance to succeed, regardless of where it ends up on this list or that. Your cause may be sharing your Wodehousian humor. Or telling a fantastic story that entertains. As long as you are clear, I think you should go ahead and take the plunge. If you are keen to share some management wisdom or 25 tips about a niche domain, please pause a moment to consult Mother Google just to know what is already out there. And to ensure you can be different, if not unique. As to the process of publishing, a word of caution. Recently, I read a self-published book by someone who has founded an institution to support a humanitarian cause. There were so many proofing errors and layout glitches that what ought to have been a good, moving series of stories had been reduced to an annoying distraction. I did not have the heart to recommend the book to anyone, lest it discredit the author and hamper the cause. Apparently, the writer had used a “self-publishing package” suggested by the publisher. Another writer (a national figure) was castigated by a much-published veteran for using a “cheap” publisher and made to republish the book under a more reputed name because the book deserved it. So, not just the writer, the publisher matters too. Pick someone who aligns with your thinking and has something more substantial to offer than projections of revenue and reputation. The randomness of it all Publishing, the knowledgeable say, is a strange, unpredictable world. Not every bestseller might be recommended reading from the perspective of your English professor. William Thackeray dismissed popular novels as “jam tarts for the mind”. However, in publishing, the hits are what sustain the business. You must have read Danielle Steel. Her 200-plus books have sold over a billion copies! As Catherine Nixey writes in her piece in The Economist, Steel’s novels are “a literary sediment, settling on the shelves of holiday cottages everywhere.” Many are the (would-be) authors who would attempt to Chandrayaan the moon, just to become such sediment! What is the formula then to make your book a hit? The wise say there is no formula or magic. Apparently, that is how the publisher Random House got its name. Again, as The Economist reports, in the words of Markus Dohle, the boss: “Success is random. Bestsellers are random. So that’s why we are the Random House.” Jonathan Karp, the chief executive of Simon & Schuster, thinks taking credit for a best seller is “like taking credit for the weather”. In 2018, Northeastern University researchers analysed almost eight years’ worth of New York Times bestsellers and came up with some tips for aspiring writers: fiction (thrillers and romance especially) sells better than non-fiction; if you must pen a non-fiction, stick to a biography; and, it really helps if your name is known. Any lessons from the bestselling authors? They are prolific, says The Economist. Danielle Steel writes until her nails bleed. Fleming recommended writing 2,000 words a day and not to sully this with “too much introspection and self-criticism”. James Patterson has churned out more than 340 books (some in collaboration with other writers). The mantra then is, “Don’t get it right, get it writ”. Bleeding nails? Just get it writ? Hmm, I am not sure. What do you think, Mr. Shakespeare? If you were to do it now, would Midsummer Night have remained just that, a Dream? Or, without Much Ado, would you have simply unleashed a digital, self-published Tempest? CREDITS

Text: https://www.economist.com/culture/2023/08/25/how-to-write-a-bestseller; https://www.quora.com/profile/Abhi-Singh-1489. Graphic: https://natlib.govt.nz/records/40382902; https://www.vecteezy.com/png/9399398-old-vintage-book-clipart-design-illustration; https://www.clipartmax.com/download/m2K9A0b1i8N4i8N4_books-for-clip-art-books-clipart-png/ With change fast and furious as always, how relevant is what your school taught you two or more decades ago? What is it that you have had to or want to unlearn to cope with today? Medscape asked this question recently about medical school. Even before I read the article in full, I shared the same question with a few doctor friends. I expected some finger-wagging about the need to keep up with technology and some frowns at the interfering Dr Google. I also expected doctors in the US and India to come up with different answers. Well, surprise! What Medscape gathered This is the gist of what Medscape gathered.

What my doctor friends said

What have you unlearnt? Yes, apparently robots are wonderful surgeons today. But the patients are not automations. The core message from everywhere appears to be to take time to listen and clasp a hand before the robot takes over.

I am grateful to my doctor friends who were kind enough to share their opinion. Special thanks to Dr Srinagesh Simha, Dr Khurshid Bhalla and Dr Pushkar Khair. So much about the medical profession. What about your profession? Is there something you have unlearnt? Is there something that was taught to you decades ago, but you disagree with today? This is one of three concepts developed to promote live liver donation. This adopts a mostly animated, light-hearted approach, targeted at the younger audience, that establishes the importance of the organ. It also tells how liver disease affects other organs. Slow zoom from the top of the room to patient in bed. Doctor and a family member talking in hushed tones. Doctor is saying everything is set for the transplant. Family member raises doubts about the safety of the surgery and the health of the donor. Doctor reassures. The zoom continues until the patient’s abdomen region is in close-up. Shift to animation. Liver is seriously ill. Lying on a bed. The other organs are around the bed. They respectfully call the liver “Dada”. Esophagus is looking very sick and bleeding. So is the stomach which has some vessels ready to burst. Blood vessels (semi-transparent with green stuff showing through) are all coiled up. Heart is emotional and crying. The wise brain is looking grim but holding the others together. Esophagus: I think I am going to bleed to death. Stomach: So am I. Heart: (Screams at stomach) Shut up! It’s all because of you. Drinking and eating all that fat rubbish like mad … now see what you have done. Stomach: But what can I do. I just try to digest what is put into me. Blood vessels: We can’t fight these guys anymore. (A green germ leaps out of the blood flow, grinning, and dives back, penguin style.) We are all going to die. Brain: Show some respect. Don’t just think of your own problems. We are with the most important member of our family. So hardworking. Cleans, makes, stores, saves—500 functions. None of us can match that. And when Dada can’t do all that, see what happens to us? Heart: Stop it! You are talking as if Dada will never wake up. Brain: Nah! It is not easy to bring Dada down. Something must be seriously wrong with the genes. Or some nasty virus. Or some terrible drugs. And, yes, the culprit might be alcohol. Just too much for too long. Stomach: But … but …. Brain: Don’t worry. Our Dada will not die. Not that easily. Just now we are waiting for a little piece of another healthy liver. That’s all Dada needs to regrow. Stomach: Really? Brain: Dada is so unselfish. You can give a bit of liver and both the giver and receiver can live. Think of it. “Live” is in Dada’s very name. So unique. None of us has such a name. They must patent his name. Heart: Quiet everyone! It is time for the transplant! Animation blurs and mixes with footage of real operation theatre. Surgery in progress. Fade out. Fade in brightening sky outside the window next to patient. Patient is sitting up, talking to a child about the surgery. Patient: And now the small piece will grow and grow and Dada Liver will be strong again.” Child: Is the liver very important? Patient: Of course! There is no other organ which has the word "live" in its name, right? So, it is very important, and it keeps us alive. Camera zooms into animation again. All organs looking happy and busy. Heart suddenly bends down and plants a kiss on liver. As liver blushes, camera pulls back to reality again. Patient: Did you just tickle me? Child: No, I did not! Patient: I just felt something funny inside. Child: Do you want me to tickle you? As they tickle each other and laugh, the camera pulls back to reveal the rest of the room. Busy nurses and doctors. And a patient on another bed, who joins in the laughter. Possibly the donor? If you are an individual or an organization interested in developing the concepts into films to promote liver donation, will be happy to share these with you. Please get in touch with me.

Today is the day, like yesterday and like tomorrow, when you will hear a couple of words a lot. This morning, I got this arrestingly misleading, three-colored message from my bank, asking me to move towards independence by taking a loan on my credit card and to increase my credit limit so that I can be free to spend more. How can a loan, or spending more (simply because I can), put me on the path to financial freedom? I went back to one poem that has stayed with me from my school days. The one that is most quoted when the tricolor is in season. Where the mind is without money fear Where the mind is without money fear And the head is held confidently high Where finance knowledge is free and sought Where the world has not been broken up into extremes By birth, faith or narrow money walls Where words speaking needs and dreams Come out from the depth of truth And are heard with true empathy By those who know more and can advise with integrity Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards freedom Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way Into the dreary desert sand of apps and influencer mirages Where the mind is led forward by simple goals Down the ever-vigilant path of thought and action Into that heaven of finance freedom, my Father, Please let us all awake. Thank you my good friend Lovaii Navlakhi, for being a patient money teacher for so long. And apologies, Rabindranath Tagore, for twisting your precious words to send this message. First published here.

Blame it on Barbenheimer? Or are we being corned into popping more into our mouth just by being in a theatre regardless of what is playing before us?

Sarah Lefebvre, Ph.D., an associate professor of marketing at Murray State University says it’s all in the mood. “When we lower the lighting, we're more relaxed, which usually increases satisfaction in general with your overall experience …. We're gonna probably consume a little more because A, we’re not really paying attention, and B, we don't really care.” Low lighting at restaurants makes you more indulgent with your choices (skip salad, have fries to fill). When it’s dim, foods with just one dimension of taste (sweet or salt, like popcorn) taste better. Add the movie distraction and bring on more popcorn! And you eat more when the air is chilly! Plus, adds this TIME report, there is the matter of close identification with the characters in front of you. Watching Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles? Keep them pizzas coming! And when those projected finish eating, you reach for something sweet too. Looks like eating more is scripted, no matter what the film is. So how much did you pay for the ticket last time? And for the popcorn? Read the complete report here:The Science Behind Why We Eat so Much at the Movies | Time The founders are selling their stake. Just another business headline. Routine. Why does it open a dam of nostalgia? Nearly 40 years ago, there was a small advertisement in a newspaper. “A reputed pharmaceutical company in Bombay wishes to launch a house journal and is looking for a qualified Journalist/Writer to assume independent responsibility.” This writer had wandered into journalism and after some two years was beginning to learn that there was more to it than writing. So, he applied. It was his first visit to a big company, as a nervous job seeker and not a privileged reporter. As the clock ticked past the scheduled hour of interview, the merry receptionist, her fingers flying over the switchboard, smiled at me, and said, “Sweetheart, I have told the manager. He will call you soon.” It was doubly reassuring, mainly because for the first time someone, a stranger in a strange setting was using such an endearment to address me. A few days after I joined, we were all friends and I asked her how she managed to make every strange visitor a “dear”, a “darling” or a “sweetheart”. It just came naturally to her, she told me. “And what is the harm in making someone comfortable, right? It’s all the family, dear!” Over the next several years, I would enjoy being part of the family which paid me a salary. Of and for the family I had suggested a name for the house journal in an ambitious note: “It is only inevitable that our number grows as we develop. All 1200 of us are per force flung far and wide. In such a big family, separated by long distances, there has to be a medium through which all of us can share our thoughts, pleasures, and plans. Tablet is meant to fulfil that need. This is going to be one tablet which will not be made in a sterile atmosphere. Here we will let our germs of ideas flourish and give free rein to our thoughts.” I might have been sold on “Tablet” but what the employees chose after a poll was a different name. What was gratifying was that very few bothered to remember my name (then and now) but the easiest way to introduce me was by the name of the magazine. The bosses insisted that the magazine must be printed and mailed home. Not simply handed over in the office or factory. It was meant for the family and had to reach the family first—both the English and the Marathi versions. Like the magazine, even its editor had the opportunity to visit several homes. To meet the lab technician who was a passionate collector of stamps. No one knew that the silent guy in stores was also an accomplished dancer until I went to his house and clicked him in action. And did you know that senior delivery guy always on the move on his bicycle, told a little lie that he could ride a cycle just to get that job? But you would pardon him when you also learnt how he had to struggle to save the animals in the laboratory when the whole locality was cut off by floods. Up and down If the editor had started feeling a little too important, the family provided enough moments to keep him grounded. Like the wrong spelling the name of the person, who had played a key role in the golden jubilee celebrations. That too on the front page of the very first issue in four colours. Like being taken to task by a worker on the packing line, who stormed across the corporate floors, probably for the first time after she was employed, to give me an earful. After all I had dared to change a couple of words in her poem published in the latest edition. What would I tell my family, was her primary concern. Like being unceremoniously thrown out of the factory because I had omitted to wear the production floor attire as I went in search of someone I was supposed to interview. The company was kind enough to give me enough mentors—like a seasoned editor from the corporate world and a veteran from the advertising arena. The latter magnanimously let me tweak a couple of words in the script for a prestigious corporate film. Always within As the years passed, the company gained enough confidence to let me loose in other areas—the Chairman’s communications, the annual report, the medical journal and even marketing (“for the largest organ, the strongest antibiotic”).

The greatest privilege was to spend time with the Chief, a name to reckon with in the world of global health. To watch his pen move deftly across the notebook as he explained the structure of a new drug in the making to a team of awed scientists in white aprons. It was as captivating as the delicate drop he loved to execute on the company parking lot that doubled up as a badminton court after working hours. Then, at other times, one could not but share his agitation as he wondered why it was difficult to put patients before patents. The association with the family would continue even after I moved on from the company. I was then a consultant for a hotel under construction in another city. One day a tall man, an old associate (and cricketer) from my employee days, walked in, ducking the bamboos sticking out from the scaffolding. He was now in charge of a new palliative care centre. He explained what palliative care was all about. He wanted a line to describe the centre. “So, what you are doing is beyond curing, right? Care beyond cure?” I suggested. Then would come my initiation into respiratory research in addition to occasional corporate requirements. My status on paper did not matter. After all, you do not stop being a member of the family, just because you have moved away. As many who were my colleagues during those days say, “You may not remain in Cipla, but Cipla will always remain in you.” Just when I thought I had distilled the secret of happiness down to some 12 bullet points after stumbling on one social media message that led me to another 99 within the hour, came this study that left me unhappy. Elizabeth Dunn, professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia, and Dunigan Folk, a PhD student in Dunn’s lab, had happily accepted all the common happiness strategies when modern science grumbled and called for more stringent studies and interpretation. So, they lined up the strategies: gratitude, social interactions, mindfulness or meditation, time in nature, and exercising. Then, as researchers often do, they ploughed through 22,000 papers involving these methods. Only 494 of those were right about the method and out of that only 57 were constructed right to yield reliable statistics. See the smiles fading? They went on to discover that even the two strategies that best withstood the rigors of scientific testing—gratitude and social engagement—could at best yield short-lived happiness. The verdict? Those tips might not work for all, and when they do, the smile might not last very long. Interestingly, the Harvard Study of Adult Development has been at it really long. It started in 1938 and has covered 2,000 people across three generations. What did the current director of the study, Dr Robert Waldinger and his team conclude? The happiest subjects through the study had two major factors in common—they took care of their health and built loving relationships with others. As one report of the study put it, “good things happened to those who had given up on changing their situation, and good news appeared when they least expected it.” I decided to ask the “scientist” accessible to everyone these days. First, ChatGPT shot 10 bullets embedded in 377 words at me. When I pleaded for a shorter answer, I got this. “The secret of being always happy is to cultivate gratitude and focus on the present moment.” Nothing artificial about that piece of intelligence, right? Bobby McFerrin almost got it right in his song. Better yet, when it comes to being happy, don’t query, just be. By the time the second round of tea was served, two hours after the day started officially, six news clippings were on the CEO’s table.

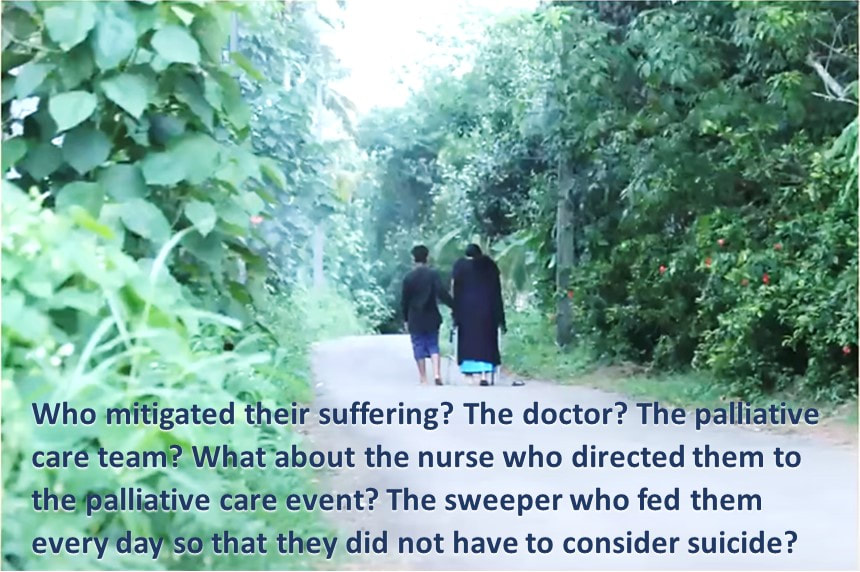

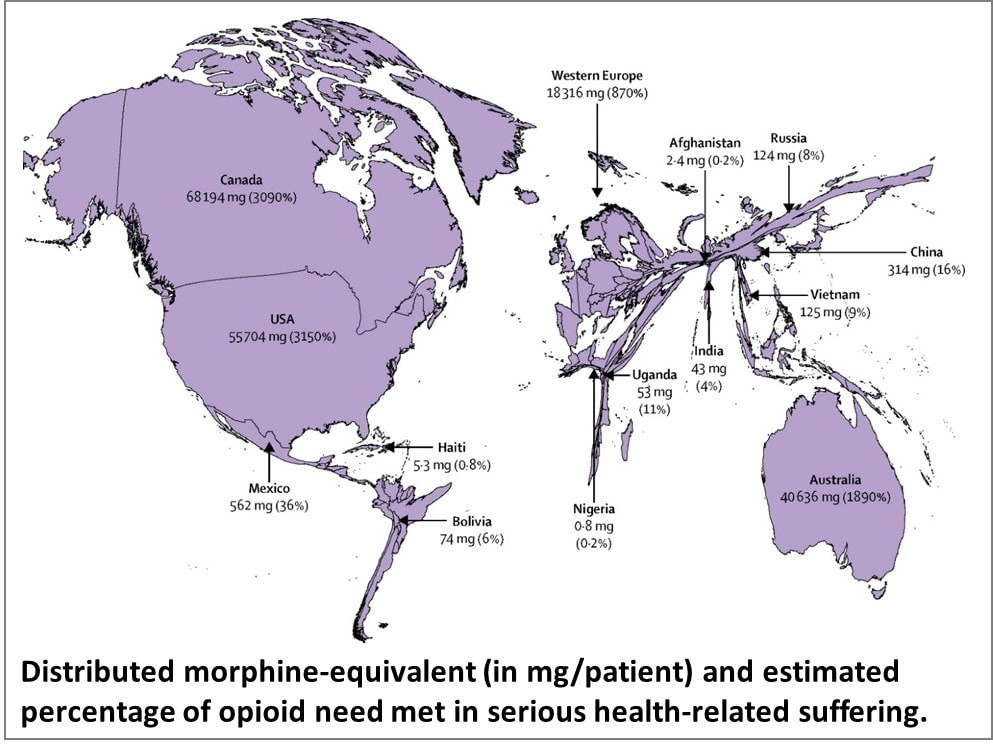

The CEO liked to be informed at once and the managers liked to have the boss liking them. It was a company that believed in staying ahead and all of them knew what it took to stay ahead. "Companies to sponsor cages,” was the gist of each clipping. The municipal corporation was trying to salvage the city zoo by coaxing private companies to adopt cages complete with the occupants. “I think we must take the lead, sir” the communications manager was the first in. The CEO squirmed, imagining the company’s neat logo adorning a stinking enclosure. “We must sit on this,” he muttered. “Right away, sir.” The manager gleefully started working the phone. Within ten minutes, all managers were in the conference room, glaring balefully at communications and each hoping the boss had noticed his clipping first. “I wonder what the others are doing,” the CEO said after patiently listening to seven different interpretations of the three-inch news. A hush descended as he said that. It meant a) it was an important project, and b) nobody knew what to do. “We must hurry up so that we can choose the best animals,” the marketing manager said. He did not particularly care for the monkeys or the rhino, but sticking to birds would have projected a weak image. “If only we could fabricate our own animals amenable to alterations as per market conditions,” he wondered aloud. That was agreed upon as a separate issue altogether, requiring to be sat on separately. For the moment, the elephant met with general murmurs of approval until quality raised the issue of sampling. Also, he saw no reason why any animal should be seen in the company’s cage without an apron. Personnel made a mental note to speak to the linen keeper. “Everything in white,” production made his point. He described the bars painted a glossy white, with matching tiles on the floor. He got a little carried away and didn’t want to spare even the tiger’s hide. “Everything must be appropriate,” the CEO reminded him. “Yes, I agree, sir,” production sheepishly conceded but fought back instantly. “There must be documented standard operating procedures. How the animal enters the cage, how it leaves, how it is fed and how it paces.” And, of course, what it can do and not do while inside the cage. Everybody looked at production enviously. What an original idea! Marketing was not one to keep quiet for too long. “The cage must be redesigned so that the logo can be large.” The suggestion to keep the animal out in case it didn’t blend with the décor was indeed radical. “We must not mix up issues,” the CEO said. Everyone nodded profoundly. “The cage and its occupant will have to be evaluated in isolation first before the two are assessed for a harmonious and symbiotic association,” the CEO elaborated to vigorous stirring of steaming cups of coffee. Personnel decided to step in. “What about discipline? We can’t have our animals behaving irresponsibly. We must enter into a contract with … with …. I mean there must be a contract—a signed copy must be in our records.” There were smirks all around, so he decided to be less personnel and more positive. “There must be training, well-structured and career oriented.” That didn’t sound strong enough, so he went on, “Let’s have a performance review every three months. In the prescribed format, of course.” The talk of training gave production an idea. “What about safety? What if there is a fire in a cage?” There was silence until a chorus of ideas burst forth. “There must be a second door for emergencies …” “But then the animals will escape …” “Include a non-escape clause …” “Every animal must learn to use a fire extinguisher …” Finally, the CEO said, “Let’s have a schedule.” Suddenly everybody was quiet. Purchase, who had been trying to get a word in, grabbed the chance. “We must have user tests. In two stages. In stage one, we take turns to host the animals. That way we have a complete idea of the user’s needs. Next, we stay in the cages to complete the study.” The meeting ended with a unanimous decision to have another meeting in the presence of the zookeeper and three or four cage attendants. The proposal to also invite a few animals was shot down as it was likely to introduce an element of bias. Two months later, the company got a letter from the municipal corporation. “… we are unable to grant your request as the SPCA has protested against the proposal of managers cohabiting with animals ….” This is inspired by a talk delivered by Dr M R Rajagopal, Emeritus Chairman, Pallium India, as part of the seminar series “Palliative Care and the Motives of Medicine”, organized by the Harvard Medical School Department of Global Health and Social Medicine. This is written in his voice with his permission. The doctors attended to her leg and restored her sight. But were they solely responsible for giving her “life” back to her? What about the sweeper who provided food every day so that she did not have to consider suicide, as her son had suggested? What about the social media support that gave a roof over their heads? What is the motive of medicine? Are we here just to diagnose and treat diseases? Or is it a bit more than that? We may have come into it for different reasons but once we are in the field of medicine, we realize what a huge privilege it is to be part of healthcare. We find ourselves in a position to make the most difference to other people’s lives. We see people at the most vulnerable times in their lives and at times become the instruments to help them rise from the depths and smile again. To actually provide healthcare for all, we may sometimes have to travel over difficult terrain. At times, we have to strike a new path because at the other end there is somebody who belongs to 84% of the global population, without access to quality healthcare. They cannot get to us, we have to reach healthcare to them where they are, when they need it. Does that sound frightening? It takes more than a doctor Ironic as it might sound, I got to meet that helpless mother and son when I was leaving a World Palliative Care Day function. The 12-year-old boy had been sent with the hope that someone would be there at the function to help his mother. Her one leg was fully wrapped in an ugly bandage. And she was blind. She was about 40, a single mother abandoned by her husband. She had been a diabetic since the age of three. Diabetes had stolen her sight four years ago. A surgeon had said she would need an above-knee amputation. Of course, she was in significant pain, “like someone is cutting my leg with an axe.” She lived in a shack that belonged to someone else. She told me about a weekend when they had to starve. Hungry and frustrated, the son said, “Mom, let us kill ourselves. I cannot bear this hunger anymore.” Mom replied, “Son, today is Sunday. Let’s wait. I will find some way.” Somehow, they got across to a healthcare center. Luckily, they found a very humane doctor there who put them up for three months before I got to see them. They survived on the meal provided by a sweeper at the center every morning. They landed at the palliative care day function where I met them first because a kind nurse at the health center had directed them there. A definition distant from reality There are several definitions of palliative care today. Most of us working in the domain abide by what the World Health Organization had stated 21 years ago. Among other things, it prescribes palliative care for those with “life-threatening illness.” Let us go back to the mother we just met. She is diabetic; does she qualify? She is blind; does she qualify? More than anything else, does hunger qualify? The same persistent hunger that almost drove them to suicide? We cannot be rendered helpless by a definition. After all, such definitions tend to come from the 15% of the world that is rich and where all the meticulous studies happen. It gets applied to the 85% of people living in low-and-middle income countries in drastically different conditions. Do such definitions bind or liberate? Let us go back to the fundamental issue. What really is healthcare? When we keep someone’s heart beating, are we providing healthcare? What is the duty of the healthcare provider? The law does not define it in India. But the Indian Council of Medical Research, a statutory body, defines that duty as: “To mitigate suffering. To cure sometimes, to relieve often, and to comfort always.” And the ICMR emphasizes there is no exception to this rule. How many of us are aware of that definition? Do we practice it? Or do we stick to what we learn from the textbooks as dictated by medical institutions in 15% of the world, the high-income world? Palliation as mitigation If you are a healthcare professional and you have not been taught how to mitigate suffering or do not accept it as your primary responsibility, we in palliative care will be happy to help you. Not that we have all the answers. At least, we try. Because mitigating suffering is our primary motive. Opioids are one of the primary tools we use for relief from moderate to severe pain. In 2017, a Lancet Commission Report depicted access to opioids (which translates to access to pain relief) across the world. You can easily make out which country is obese, and which is malnourished when it comes to opioid access. The trick is to strike the right balance between easy availability and the necessary restrictions to prevent abuse and misuse. While we applaud western European countries for getting that balance right, let us not forget Kerala. In this tiny state right at the bottom of India, access to opioids is 16-times more than the national average. In the low-income Uganda, opioid access is three times better than what India claims. So, this shows it can be done. But why is it not happening universally? Is it because relieving pain or mitigating suffering is not a commercially attractive proposition for the industry that is at the heart of healthcare? Adding cost to suffering A study published by The Lancet on December 13, 2017, pointed at a vulgar disparity of life (to borrow Arundhati Roy’s expression). Not only are we not doing what we ought to be doing, but we are letting catastrophic healthcare expenditure add to the pain. The study aimed to estimate the global incidence of what they called catastrophic health spending. They measured this by the percentage of people whose out-of-pocket health expenditures were large relative to their household income or consumption. You are welcome to read the study for yourself. Personally, I was saddened and shocked to note that India was among the 12 countries burdened the most by the cost of health: more than 55 million Indians driven below the poverty line by what they had to spend on health; 38 million of them by cost of medicines alone. Such catastrophic health spending is not only for living with an illness; it is also for end of life—with the dying process excruciatingly stretched out over weeks or months in a desperate effort to prolong life at all costs. Are we afraid of death? Do we tend measure the “success” of medicine by how long it can keep death away? Is it difficult for us to accept that if life were a sentence, death is simply the full stop at the end of it? In January 2022, drawing on multidisciplinary perspectives from around the globe on the value of death, the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death argued that “death and life are bound together: without death there would be no life.” The Commission proposed a new vision for death and dying. It called for “greater community involvement alongside health and social care services, and increased bereavement support.” Cruelty of forcing to stay alive Moving away from professional studies and reports, let me narrate a personal experience. One of the professors who taught me medicine developed dementia. She was not swallowing well, so she was put on intravenous feed, against the advice of many of us. She would keep pulling the tube out. So, they tied her up. As every doctor knows, physical restraints can cause a 44-fold increase in the patient’s agitation. She did become more violent, and they promptly tied her up tighter. Eventually she was intubated and ventilated. The family had to walk in every morning and every evening for five minutes each, watching their beloved person being killed in order to be kept alive. Her daughter lamented, “Here was a person who gave a lot of love to a lot of people. Did she deserve to die this way?” Even as I write this, the daughter is receiving psychiatric treatment. I do not think she was affected so much by the loss of her mother as by the cruel way medicine kept her alive until the last excruciating moment. Why do our efficient, kind-hearted doctors refuse to accept that death is a part of life? Why do they hold on to the mistaken belief that it is their duty to prolong life at all costs? Is life merely a beating heart? The National Cancer Grid, a brilliant conglomerate of about 300 cancer institutions in the country launched the initiative Choosing Wisely India around 2020. The objective was to “identify low-value and/or potentially harmful practices in cancer care in India.” It intended to “facilitate a conversation between patients, clinicians, hospitals and policy makers on delivering high quality, affordable cancer care.” The aim was also “to reduce unnecessary interventions to improve overall quality of care, reduce patient toxicity and reduce the financial burden on both the patient and the system.” One of the recommendations was, “Do not treat patients with advanced metastatic cancer in ICU unless there is an acutely reversible event.” Laudable, isn’t it? But we all know what happens in hospitals. A friend, a senior neurologist, once remarked that our corporate hospitals are like fortresses that the poor cannot get into, and the rich cannot get out of. I do not think he was joking. A 2019 JAMA paper stated that in European intensive care units, 90% of all patients were taken off life support and offered palliative care once it was clear further treatment was futile. And, in comparison, what is the situation in India? Only 30% are taken off futile life support, that too any without palliative care support. As much as 70% of them die in ICUs. The end is stretched, hour by cruel hour for the patient, day by interminable day for the family. Helping us is up to all of us Let me get back to that woman and her son one more time. Yes, we treated her symptoms and pain. That was relatively easy but definitely not enough. One of us posted her story on social media and requested help. Help came. We now had money to pay for a caregiver while the patient underwent retinal surgery. After years, she got to see her son again. A diabetologist and podiatrist helped her get back on her feet, with support. She held her son’s hand and walked to a new home, where they are now supported by a monthly allowance, thanks to donations from the community. There is a huge gap between what healthcare is and what it ought to be. No doctor and no palliative care specialist can fill it by themselves. Does that mean we hide behind a definition and shut our eyes to the problem? The German physician Rudolf Virchow had said: “Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing but medicine on a large scale. The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them.” Our palliative care team is taking small steps. We are far from perfect, and it is a huge mountain to climb. But we are trying. By doing our best to support patients. By talking to the community about what we are doing and how they can help. There are many who want to help. But do not know how. Money is not the only way. I believe it is beginning to work. It has to. Right now, it is up to us to solve this social, or rather, humanitarian problem. Every World Palliative Care Day is a special occasion when those who can help get together with those who need help to celebrate life. One such day, in the city of Thiruvananthapuram in Kerala, some 40 people came to the beach to wet their feet. So, what was special about that? These were all people confined to wheelchairs who could barely move out of their homes. It took four people to move each of them from home to the beach and back. So, it took about 160 people to make this happen. All doctors and nurses? No! They were students from two engineering colleges.

And what was their reward? One of the patients was a paraplegic who did not have normal sensation in her feet. She said, “the waves touching my feet is the best experience I have had in my whole life.” She couldn’t stop smiling. That was their reward. And that is the reward for all of us when the community joins hands with palliative care and medicine to mitigate suffering in the true, complete sense. We have a long way to go. We have just wet our feet. |

AuthorVijayakumar Kotteri Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed